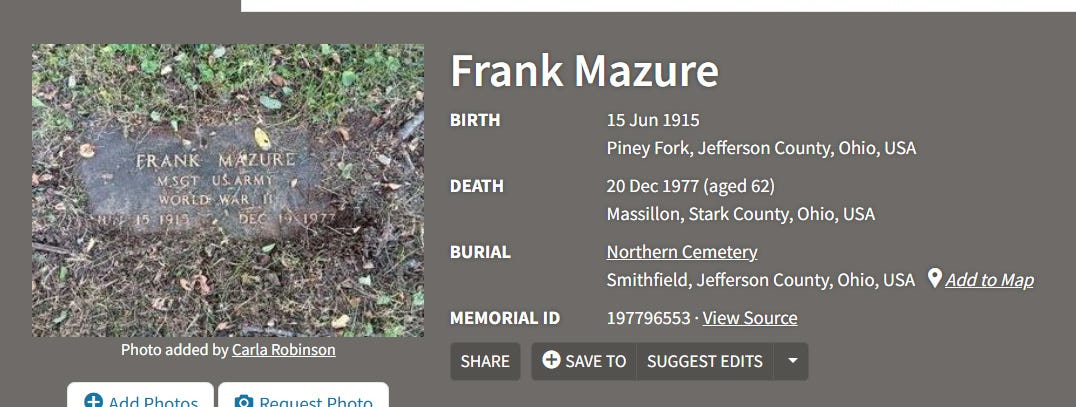

My recent conversation with Clark Mazure, whose father was a maintenance sergeant in the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served, led me to revisit my 1996 interview with Eleanor Mazure, Clark’s mom. I never met Frank Mazure, Clark’s father, as he passed away before I started going to reunions.

Eleanor Mazure: We lived in the same town, a small coal-mining town in Ohio, on the same street. There were about, oh, let’s see, eight or ten houses on each side of the street, and he lived down at one end and I lived at the other end, and that’s when we met.

Aaron Elson: How old were you?

Eleanor Mazure: I went with him for five years before we got married, so I was 16.

Aaron Elson: You were 16 when you met, or when you got married?

Eleanor Mazure: When we met.

Aaron Elson: Was your father a coal miner?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes.

Aaron Elson: So you must have had a big family. All those coal miners had thirty, forty children. [I can’t believe I said this, what was I thinking, but it’s there in the transcript!]

Eleanor Mazure: I came from seven children, and Frank came from 13. But a lot of them didn’t survive until they were adults. I think there were about five or six lived to adulthood. Some passed away.

Aaron Elson: And your dad, was he a coal miner?

Eleanor Mazure: My dad was a coal miner; all of my uncles, all of my grandfathers...

Aaron Elson: That must have been a tough life.

Eleanor Mazure: Very, very tough.

Aaron Elson: A lot of drinking?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, that was about the only recreation that the miners had to do. Once they came home from work on weekends, there wasn’t much in a small coal-mining town in those days.

Aaron Elson: And where in Ohio was it?

Eleanor Mazure: This was in a place called Piney Fork, Ohio, and Piney Fork is about 20 miles south of Steubenville.

Aaron Elson: Okay, so you were 16, and was Frank older than you or the same age?

Eleanor Mazure: Five years older than I.

Aaron Elson: Did he work before he went into the Army?

Eleanor Mazure: He worked in the coal mine for his, it was what they called the tipple. The tipple’s on the outside of the coal mine, because he didn’t want to go underground, so he worked on the tipple where the coal came out and it was dumped into the coal cart, the destination. So he worked there a short period of time.

Aaron Elson: Why do you think he didn’t want to go underground? Was he claustrophobic?

Eleanor Mazure: I don’t think there was any particular reason, I just think he probably foresaw that there wasn’t any future there. And he told us there were two fellows that he kept telling us for a long, long time that he was gonna go to the Army, and nobody believed him. So he and another fellow went down to the recruiting place and signed up.

Aaron Elson: And what year was that?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he went in in 1939.

Aaron Elson: So he kept telling people he was going to go into the Army and nobody believed him?

Eleanor Mazure: You see, because in a coal-mining town in those days there wasn’t any future, you know; if you started to be a coal miner, that’s who you would end up. So that’s what he chose to do, and he and another fellow went to the Army.

Aaron Elson: Did they go in the same outfit?

Eleanor Mazure: No, he [Frank] went directly to Fort Knox. And then from Fort Knox, I don't recall if it was in the first or second year, but he was sent to, wait a minute, first they were in cavalry.

Aaron Elson: Oh, so he went into the horse cavalry.

Eleanor Mazure: Yeah, because they wore these pants, you know, these jodhpurs, I think they're called, but then later on he changed to armor. And he was sent to Aberdeen, Maryland, to ordnance school, and that's where he learned how to be a mechanic on the tanks, and then from there he graduated, okay, we were supposed to get married on the post but they only got three days' leave in between Aberdeen, Maryland, and Pine Camp, so we just got married in Steubenville. We got married on November the 3rd, 1941, one month before Pearl Harbor. So we went up to Pine Camp on the bus.

Aaron Elson: How much did he make; was he a sergeant yet?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he went in as a private, and each step, he didn't skip any, and he wasn't elevated, you know, because he was elevated on his merits, and then there had to be openings; plus I encouraged him. I always said, “You can do better, you can do better,” so he ended up being a master sergeant in Service Company. So, as I say, a month after we were married, the war started, and that changed everything. In the beginning he was making $21 a month, for a long, long time. I don’t recall how much more he made when he was a Pfc, but he was already either a sergeant or a ...

Aaron Elson: Corporal?

Eleanor Mazure: No, corporal is below a sergeant. There was sergeant, first sergeant, tech, and then staff. So he was probably already a tech at least, I think, but I'm not sure. And then he became a master sergeant. They wanted him to go in and be a higher-up, but he didn't want to get out of his unit. He enjoyed his men; he enjoyed his men immensely. When he came home, this doesn't have anything to do with this period, but when he came home from service, I don't know if he was shellshocked or what, but he used to get up in the middle of the night and start packing his barracks bag and crying, “I’m going back to my men. I’m going back to my men.” He cared so much about the men, you know. As I look back, I think, well gee, in those days you didn’t realize how the world was going to (unintelligible), but he really, his heart was really in it, because he really wanted to stay in. But of course the war changed it, changed him, because, well, it just did, it's hard to say.

Okay, so we're in Pine Camp, and we lived there...

Aaron Elson: Now, how did he propose? Did he say, “Let’s get married?”

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he, okay, when he went into the service, he said, “When I get through with all my schooling and everything, I’m gonna send for you.” So we got engaged through the mail. And he sent me my ring through the mail, and then he did keep his word, because after he got out of school, he came home and got me and we got married in Steubenville, and then we just got on the bus and went to Pine Camp.

Aaron Elson: So you got on the bus and went up to Pine Camp. Did you know Forrest Dixon's wife, then, at the time?

Eleanor Mazure: No, I didn't. I knew the officers slightly, but because in those days the officers were sort of separate from, in other words you didn't live together on the post, but we got there too late to find; he would have been eligible for us to live on the post, but we didn't have a car so we got up there too late to find accommodations on the post, so we had to go out and scout for a place in the town. I don't recall the name of the town, it was real small, but it was about three miles from camp, from the gate, and he walked up there every day, and I got privileges to go on the post and shop.

Aaron Elson: So you had to walk three miles to...

Eleanor Mazure: Unless I went to the little neighborhood store. And I had asked for credit there because, well, Frank was a poor guy and so was I, so we lived with some real nice people. They made accommodations for us upstairs in their home, and it was really great, we just, we lucked out.

Aaron Elson: How much rent did they charge, do you remember?

Eleanor Mazure: No, I don't. It wasn't much. But we got along real well. We did our washing together and everything. Another thing I did, I felt, I had heartfelt, I felt sorry for all these fellows because I knew eventually they were gonna go overseas; every Sunday I invited, he invited at least three fellows over for Sunday dinner. In the afternoon I would cook something that he really liked, because we had, he had fellows from Pennsylvania that used to come with him; I cooked cabbage rolls, spaghetti, I just felt that was my little contribution toward making Frank happy before they went overseas. And when we left Pine Camp, we went back to Fort Knox then. And then from Fort Knox, I don't recall how long we lived there but we were transferred down to Camp Gordon, Georgia, and then to Fort Benning. And of course from Fort Benning they were transferred to Fort Jackson, and that was where they left from, where they embarked from.

Aaron Elson: Now did you travel in buses, or train, or how did you...

Eleanor Mazure: We traveled on whatever was available. Most, I traveled on trains because, from Louisville we went down to, on train, or bus, because we didn't have our own vehicle.

Aaron Elson: Now, what was your maiden name?

Eleanor Mazure: My maiden name was Berdjar.

Aaron Elson: That's Polish?

Eleanor Mazure: Slovak.

Aaron Elson: And Frank was what?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, one of his parents was Polish and one was Hungarian, I believe.

Aaron Elson: How many generations back did your family go? Had your father come over, or your grandparents?

Eleanor Mazure: My father came over from Czechoslovakia when he was seven years old, and my grandparents on both sides came from Czechoslovakia. My mother was born here in Johnstown, Pa. But all of the, my grandparents, somehow, when they came from Europe, see, we don’t know that history, we didn't go into it, but they all came to Pennsylvania and maybe were coal miners for a short period of time, and then they transferred to Piney Fork, where we all lived. And that was the Hanna coal mining area, everybody knows it, it was a real big operation at the time. They’re no longer in operation.

Aaron Elson: Were there strikes?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes, there were strikes.

Aaron Elson: And accidents?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes, there were accidents. When there was an accident, a miner got killed, they would ring this loud whistle. The whole town heard it, and then we knew that there was a tragedy. The men used to go in on cars; they'd sit in these cars, they were open cars, and they’d sit on them, and it would take them into the mine and then bring them out at night, and it’s hard to imagine, but the coal miners never saw daylight for many months out of the year, because they would go in in the morning when it was dark, and when they came out at night it was dark. And, this is funny, but the miners always had different omens, and if sometimes they would see rats in the mine, and the rats would start running, then they knew there was going to be a cave-in. And there were several other things that they knew, and then they would clear the area. Anyway, in the beginning, see, miners were very low-paid. It was a very low-paid occupation but later on, a lot of people didn't like John L. Lewis but the reason, it was because of him that the miners gained some benefits, so we have to thank him. But, you know, Frank didn’t even have, he didn’t have a high school education.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Eleanor Mazure: No, he didn’t, because in those days, the high school was seven miles away and you didn’t have the money to pay the bus fare to get to, you know, so he only went through eighth grade but he did work his way up, I have to say that. Nothing was given to him. He worked. I even asked Dixon at the last reunion, I said, “How did you ever choose Frank to be your motor sergeant?”

And he said, “Do you think I’d pick somebody that didn’t know anything? I picked the best.”

Aaron Elson: How did you feel when you knew he was going to go overseas?

Eleanor Mazure: Well naturally, we all felt very badly. We took it kind of hard.

Aaron Elson: Were there other wives in the same...

Eleanor Mazure: Yes. I came home. We departed, we stayed there as long as we could in Fort Jackson. We stayed there until the last minute, in fact the last, they didn’t know exactly which day they were gonna leave, so this one particular night it was raining as hard as it could rain, so a couple of us went over near that area and the fellows somehow, I don’t know if they came over by the fence or what, I don’t recall, but they snuck out to see us for a little bit, and that was the last time we saw them. So I came home on the train with Fernandez’s wife and Mrs. Graley, West Virginia there. And that was it. But naturally we felt badly, and the thing of it is, we had been there nearly like, let’s see, like three years, and I was pregnant. I was gonna have a baby when he went over, so naturally, you know, that was... So anyway, my first son, his name is also Frank, and he was born while they were in the thick of the fighting.

Aaron Elson: So you were pregnant when he went overseas?

Eleanor Mazure: Yeah, see, because we didn’t know they were gonna go. So ...

Aaron Elson: Is he still alive?

Eleanor Mazure: My son?

Aaron Elson: Yes.

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, yes.

Aaron Elson: Because I’ve only met Clark.

Eleanor Mazure: Well, this other son, he lives about, oh, 35 or 40 miles from me, he’s also a Vietnam vet. But Clark’s the one that’s interested in the history. [When I spoke with Clark the other day, he said that Frank had passed away, and that his health had been seriously affected by exposure to agent orange while he was in Vietnam.]

Aaron Elson: Okay, so you were pregnant with Frank Junior.

Eleanor Mazure: And then they went overseas, yes. And he was born on July the 9th, and they were in the thick of battle, because they had, I’ve forgotten the name of it but they had some way that you could send a telegram to the fellows to let them know. So I was in hospital, I remember when I woke up I kept saying, “Did you let him know? Did you let him know? Did you let him know?” But he didn’t get the message for three weeks, because they didn’t know where they were. So he said all his friends were congratulating him, “I didn’t know what they were congratulating me for because I hadn’t seen it.” And so Frank was a year old the week that he came home.

Aaron Elson: Who named him? Did you decide in advance?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, I guess we sort of decided together. I could tell you something about that name. We named him Frank Fillmore, for the middle name, and Fillmore was one of Frank’s good buddies. I never got to meet the man because he never came to any reunions, but he thought so much of the man he said, “We have to name our son Fillmore,” so that was his middle name, but I never got to tell that man; they tell me he’s sick, I don’t know.

Aaron Elson: That would be Fillmore Enger [who was named after President Millard Fillmore].

Eleanor Mazure: Yes.

Aaron Elson: I’ve never met him.

Eleanor Mazure: I don’t know, what else can I tell you?

Aaron Elson: While he was overseas, did you have contact with his mother?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, his parents were already passed away.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Eleanor Mazure: M-hm.

Aaron Elson: Both of them?

Eleanor Mazure: M-hm.

Aaron Elson: So I guess his father died young...

Eleanor Mazure: No, his mom died; she was kind of young, she had severe heart problems. His dad was older, but they weren’t that young. They were older.

Aaron Elson: So both his parents had died. It must have been pretty nervewracking for you with him overseas. It must have also been very tough. How did you support yourself, and survive? Did he send money home?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes, in those days, though, you know the pay was so low, well, I came back to Cleveland and I found a little two-room, through one of my relatives I found a little two-room efficiency, and I survived. I managed. You manage. You did without. You were used to doing without if you were a coal miner’s family, you know, you did with what you had and you made the best of it.

Aaron Elson: Now, what was that about a three-cent loaf of bread?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, up in Pine Camp they had a commissary, it was, the men could do some of their shopping there, so I got a little ID, it’s a metal pin with your picture on it, and I would go up there. I would walk up, and they’d let you in once they saw your ID, and the bread was three cents a loaf. And I don’t remember too much about the other prices but they weren’t much. But you know, how much could you carry? How much could you carry home? I really, Frank loved the Army, and I loved it too. I love traveling around.

Aaron Elson: What was that about the smoky trains?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, you asked me how we got down to the different camps. Well, during the war, everything was used up for the war effort, so in my Louisville (unintelligible) train it was so smoky and so dirty and so puffy, that when we got down there we were loaded with soot. But that’s the way we had to travel.

Aaron Elson: Now, Frank Junior, he went to Vietnam?

Eleanor Mazure: It was almost like a repeat. Yeah, he was in the Reserves, okay, for like six or seven years, and his unit from Cleveland was the 233rd Quartermaster Corps, and there were about 230 fellows who were called up, and he was one of them. So in his case also, he had been married I don’t know, a year or two, and when he went overseas, his wife was pregnant. Not expecting to go. So his little girl was a year old when he came home. It was unreal.

Aaron Elson: You don’t talk about him much.

Eleanor Mazure: Well, I didn’t realize I could contribute something, because Clark is the one that’s into the history.

Aaron Elson: Was Frank Junior, did he come home, was he affected by being over there?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he’s okay, I mean, you know, he came home alone.

Aaron Elson: Alone?

Eleanor Mazure: Sure. They came home one by one. There wasn’t anybody to greet them like there was the other fellows. But he was all right. I think he’s a nervous person, but other than that, he didn’t use Vietnam as a crutch, like some fellows do. He just said, well, you have to go on with your life, pick up the pieces and do the best you can do. So I don’t really mention him because I don’t ...

Aaron Elson: And when was Clark born?

Eleanor Mazure: He’s six years younger than Frank, so he was born in 1951.

Aaron Elson: Frank Senior, he really loved the Army?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, he loved the Army, yeah. He would have stayed in, but he wanted to come home and see his child. And then they were going to send them over to the Pacific, and I think the fellows thought they had enough, being on the one front. But I have to say that he was very happy when he was in the service, and if he could have stayed in he would have been the happiest man on this earth because he just loved it so much, I can’t stress that enough.

Aaron Elson: How did he pass away?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, he had a lot of things wrong with him. He was in the VA Hospital for a long, long time. He had hurt his foot in one of the tanks once, his knee, and he never put in a claim for it. So periodically, his knee would give out and I thought he was faking. But he ended up, he had a brace on his knee, and I think he had a stroke, and he had all kinds of things wrong with him, so then, you know, it just took its toll on him, and that was it. He had numerous things wrong with him, so they just all, you know how they take their toll and add up, and he just, one morning, he just keeled over, he was sitting in a restaurant, and he just keeled over.

Aaron Elson: How old was he?

Eleanor Mazure: He was in his, you know I get a little confused on all these people that died because my little granddaughter died when she was 2, Clark’s little girl died when she was two years old. And Mom died and Frank died, they all sort of died real close together, I’m getting the dates mixed up, not because I’m forgetting but it’s just such a ...

Aaron Elson: But what year was that, then...Clark’s little girl died or Frank’s little girl?

Eleanor Mazure: Clark’s. Clark’s little girl died when she was 2. She was born with a congenital heart defect, and she had a couple of heart operations, and she survived the one when she was five months old and later on another one, but when she was two then, she had another one, and she didn’t survive that one. She was in RB and C in Cleveland [University Hospital Rainbow Babies & Children], which is a special children’s hospital, but she didn’t make it, so that’s been one heartache, you know, he’s carried, but he has three other children.

Aaron Elson: Would Frank come to the reunions?

Eleanor Mazure: No, he never came. He just, I can’t tell you, I don’t know. It’s just Clark that got interested in history, and that’s it. He just sticks with it.

Aaron Elson: About what year was it, it was the year after he passed away that you first came?

Eleanor Mazure: The first year I came was Rockford. But Clark came a year previous to that, which was a small reunion. I think the Service Company had it. It was in Detroit, Dearborn or Detroit, and the reason we found out about it was, Clark was always connecting himself with his veterans at his work. He worked for Caterpillar, and the one man was a World War II veteran, so Clark would every opportunity he would get he would talk to, so one day this man gave him one of the magazines, I don’t know if it was VFW or American Legion, and the 712th was listed in there that they were gonna have a reunion, so that was this little mini-reunion up in Michigan. So he went to that, and then the next year was Rockford, and he said, “Ma, you have to come to that.”

And I said, “Well, you know, I don’t know if I’m going to know anybody there anymore.”

He said, “Well, you’re gonna come anyway.”

And he had been corresponding with [Ray] Griffin also, putting the pieces together, so I went, and I’ve been coming ever since. Because I remembered a lot of the people there.

Aaron Elson: And you save up all year for this trip?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, you know, you manage; this is my highlight of the year. I don’t go on other vacations anymore. I used to, when our kids were small, we used to go, but this is my highlight of the year.

Aaron Elson: And where do you live now?

Eleanor Mazure: I live in, well, it’s like a suburb of Cleveland. I lived with my folks for a long time, but then, what happened is, don’t put this on the tape [I chose to leave this in because it touches upon an important part of American history], our neighborhood changed. My folks owned a home down in Cleveland and our neighborhood became a ghetto, you know how the inner cities do, so then my folks had to move. They moved out to Aurora, Ohio, which is where Sea World of Ohio is, and I have three brothers and they’re all single, none of them got married, so they bought a home and made a home for my parents. And then I moved out that way and I lived out of Cleveland for about, oh, I don’t know, ten or more years maybe, and then I moved back in, because I was driving to work from 40 miles a day one way. But you have to drive where your work is. You can’t always live on top of your work.

Aaron Elson: And what kind of work did you do?

Eleanor Mazure: I worked in a hospital for 28 years. I did various things, I worked in admitting, I have a lot of volunteer hours in, because I like people, I like helping people, that’s part of my makeup. And then I ended up, and I was a cashier, but I ended up being a claims person, claims processor they called it, and I’ve been doing all of the insurances but plus, I’m an expert Medicare biller, because I started to do Medicare, which I didn’t want to take but the boss said, “Eleanor, you have to try it for two weeks,” nobody else wanted the job. So they put me in it, and said “Two weeks,” and it ended up being like 18 years or something.

Aaron Elson: So that must have been when Medicare was first ...

Eleanor Mazure: The first day it was initiated they put me on it, and there wasn’t anyone at all to teach us, we had nothing. No one knew anything about it, the government just initiated it, and you had to pick it up on your own. And I did. And I didn’t mind it, I loved it, because basically I’m a hard worker.