A death in the Bulge

A tank battalion's toughest loss

“George kitten. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

“George kitten?”

“Yes. George kitten.”

“Oh.”

“Everybody liked Colonel Randolph,” Jim Cary said. “He was a Southerner, friendly, a very down to earth person.” Captain Cary, the original B Company commander in my father’s 712th Tank Battalion, was wounded on the battalion’s first day in combat, July 3, 1944. Because of that, he said, “my contacts with him were limited. I basically got to know him when I came back in September.

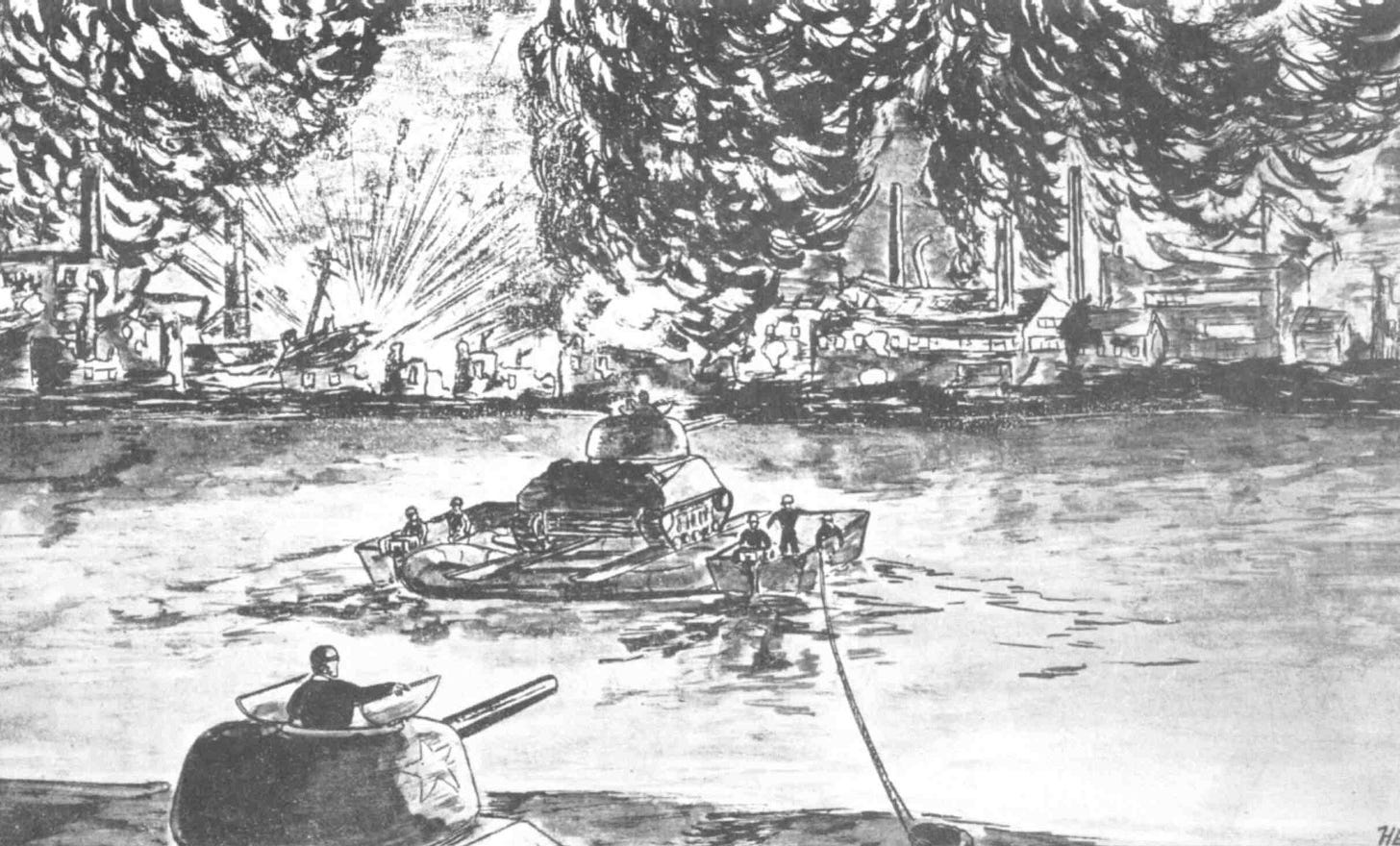

“It wasn’t very long after that that we got in this operation closing up to the Saar. As I remember it, the plan was for the 90th Division to go across the Saar [at Dillingen] and establish a bridgehead , and then the 10th Armored would attack through that bridgehead and go up towards Frankfurt.

“Right where we went across was the first belt of the Siegfried Line. It was pretty rough going. The first assault that went across was strictly infantry, and they got into a very bad situation. The Germans really wanted to wipe out that bridgehead, and they threw everything they had in the area at it. They were rolling up on the flank, and the only way the Americans could stop it was to turn all the artillery they had in the area loose on this German attack. I heard figures like 30 battalions of artillery. I really don’t know how many battalions, but I saw what happened afterward, and that was the most horrible sight I ever saw in the entire war, and something I still visualize at times.”

“Can you verbalize it?” I asked. We were speaking at the 1994 “mini” reunion of my father’s 712th Tank Battalion in Bradenton, Florida.

“Yeah. We had this fairly shallow bridgehead. Here’s the Saar River, and they were trying to go up this left flank, and they were doing a pretty good job of it. There were GIs along a road here, and this extremely intense artillery fire came down right in the middle of that concentration of troops. It was very shortly after that that we got our tanks across.

I had a platoon that was out here on this flank, and I used to have to ride through this scene, and there were bodies absolutely stacked one on top of the other. There must have been eight or nine hundred bodies in that area with parts of their heads blown off. I remember one case, a German had fallen face down in the road and it was muddy, and cars were driving back and forth over him, and I kept asking myself, ‘Why doesn’t this bother me more than it does?’ You get so immune to it.

“You could almost see what had happened. There were GIs in this shallow ditch along the edge of the road and they had gotten shot, some of them shot by the Germans, some of them caught in the artillery barrage. They were frozen in position, some of them sitting up. It was a terrible thing to have to go through day after day.

“Anyway, we got the tanks across, and one of our tanks threw a track. It was on the side of a hill, and we couldn’t get it out. We had to destroy it when we pulled back.” The battalion was ordered to retreat across the Saar because the Battle of the Bulge had broken out 100 miles to the north.

“We got orders to pull back,” Cary said, “and got into this very slow, very poorly done operation in ferrying these tanks back across the Saar. The infantry pulled out and we were left with tanks strung out along the Saar River there. I finally got hold of Colonel Randolph on the radio and asked him to do whatever he could to put a smokescreen down, because they could have knocked out everything we had.”

“We did get some smoke, and we did slowly get the tanks back across the river,” Cary said. “This withdrawal was all started because of the Battle of the Bulge. I might add a couple of other things about this withdrawal: The American army is not very good at retreating, I’m afraid.

“There came a stage when enough had been pulled out of that bridgehead where the control started to disappear, particularly after most of the infantry was gone. And I was down near the headquarters where they were directing this withdrawal, and you couldn’t get a straight story from anybody about what you were supposed to do. I was upset about it and I was sort of wandering around outside, it was at night, and this MP came up to me and said, ‘What am I supposed to do with these civilians over in this church?’

“I said, ‘I don’t know. What were you told you were supposed to do?’

“He said, ‘I was told to leave them. But the building next to it is full of C-2 explosive and they’re gonna blow that before they pull out of here.’

“I said, ‘Who do you take your orders from?’

“He said, ‘They’re gone. I can’t leave those civilians there.’

“I said, ‘You sure can’t. Just get them out of there, and if anybody comes back at you, tell them I told you to do it.’ So he moved them. And then we did get back across, and I was standing on the other side of the Saar River when they blew that. The whole skyline lit up. It was one of these scenes like, you remember what the burning of Atlanta looked like in ‘Gone With the Wind’? Very much like that. The buildings were silhouetted against the sky and behind the sky there were all these flames, and the sky was red. It was quite a scene.”

“Then we got into this wild march up into the Bulge, over roads that were icy,” Cary said. “We were all on our own. We knew where we were supposed to go but each company was on its own.

“I guess it took us two days to get up there. The course we were supposed to follow was pretty well marked out. Part of it was mountainous. I remember tanks turning, hitting ice, sheets of ice on the road, spinning around and ending up halfway hanging over the edge of the road and almost falling in the gullies. I remember a long, narrow road with trees closing over the top. It’s one of those things that gets imprinted on your mind.

“Finally, I thought we were going a little too slow. We knew there was going to be an operation on January 9th, and here it was January the 8th, sort of middle of the afternoon. There was sort of a chain of hills and mountains, and the road was winding back and forth through this. I went out ahead of the company, and I noticed a road outside of the mountains that looked like a very good road. So I went down there in my jeep and found that it was a much shorter, more direct route. Everything was fine. I thought, gee, that’s great. So I took the tanks out of the mountains down on this road. And by the time we started down that road it started snowing, and the road was completely obliterated. You couldn’t see anything. The only thing we had to guide the drivers was a fence that ran parallel to it. But the second we came out on that open country, they started shelling us pretty heavy. I didn’t realize we were going to be under German observation. We finally got through there. That was a mistake for me to do that, but it saved us about two hours

“We got the tanks in, and I remember coming down this rather steep road into this encampment area, and Colonel Bell, who commanded the 359th Infantry, was amazed that we had gotten there and very pleased, and he apparently said something to Colonel Randolph about the success of the movement. We spent the night in that bivouac area, and it was the next morning, as we were coming out I was leading the company and the line of tanks. The road curved around, and as you curved around there was a road junction. The arrangement was that the 359th would have three guides there, each one assigned to one of the three platoons in my company, and they would guide that platoon of tanks to their battalion to support them during the day’s operation.

“It was just as we were coming up to this road that Colonel Randolph was waiting. I stopped and talked to him briefly, and he expressed his pleasure that we had done so well in getting the tanks up there and he was real happy about that. And that’s the last time I saw him.”

“Do you remember anything further about that conversation?” I asked.

“It’s kind of personal,” Cary said. “I kept it general. What he said was that I was doing a wonderful job, and I said it wasn’t me, it was the whole company. If I had a bad company I couldn’t have gotten it up there. So that’s basically what he was saying. We shook hands. I liked the guy. I hadn’t really known him too much before that.

“Then we came around that corner and that exposed us. This was in Nothum, Luxembourg, and the Germans laid in on us awfully heavy as we came around the corner. They had that road junction zeroed in, and the shells were really flying. I was in the 105 tank, the tank with a 105-millimeter gun. We came up to the road junction, and the guides weren’t there. So I jumped out of the tank and started running around looking for them. I started first toward the German lines, realized that was the wrong direction to go, came back, and by that time the guides had shown up and we were getting the platoons moved. I didn't think anything about my tank because I was trying to find the command post where I was supposed to report in.

“I found the the C.P., and I guess it was ten or fifteen minutes later I saw my communication sergeant who worked in that same tank. The tank had taken a hit, right in the side, a large high explosive shell, and as I recall it actually ripped the weld open on the tank, and of course gave everybody inside a terrible blow, but nobody was seriously hurt. They really got their bells rung. But I wasn't very popular with them, you can imagine when I left that tank on that zeroed in intersection. Dumb thing to do.”

“Where were the other tanks in the company?” I asked.

“They were behind my tank, but by the time I came back the guides had shown up and they were already pulling around me; the tanks were being deployed. In fact, they were very rapidly deployed because all of them wanted to move as fast as they could. And it was my mistake that I didn't tell my tank to get the hell off of there, too, because I wasn't quite sure where I was going. But I found the C.P. over to the left. I've got a photo at home of that C.P. It was taken inside the C.P. Colonel Smith — they called him Foxhole Smith; he was anything but a foxhole type, he was a real tough guy — was in charge of the assault. I was more or less directly under him. And above him was Colonel Bell. Colonel Bell was there too, in this C.P. It was a shattered building, and I looked at it, because we walked in there and saw this front window was completely blown out, and the roof was gone. I saw this one solid wall over there, so I said that's the place for me. I got as close up against it as I could, and that's where that picture was; one reason I knew it was me is because I could see how well I was hugging that wall.

“Anyway, General Van Fleet came in. And then it wasn't because he arrived, but that was just about the time the attack really started moving, and they laid in on us the heaviest artillery I've ever encountered in my life, really terrible. And an awful lot of it was screaming meemies. A regular artillery shell that goes up and down like this, you could hear it and tell by the sound how close it’s gonna come. A screaming meemie you can’t. They fire these things like a shotgun, in barrages, whole squares of them, and they have this sound and the sound is all around you. You have no idea whether that’s gonna land right in the middle of you or gonna be off to the side. And it has a psychological effect on you, particularly after a while. And those things were screaming, and coming in and pounding and hitting all around us.

“At one stage Colonel Bell and I got caught outside the C.P. and there wasn’t any cover anyplace except a concrete chicken house we both saw about forty yards away. So we had a race to get to that chicken house, and I beat him. I mean rank had no privileges on that day. I dived in ahead of him.”

“Were there chickens in it?” I asked.

“I don’t remember any chickens, other than my feelings. Anyway, back in the C.P. General Van Fleet came in and was standing in the C.P. when we got hit with a burst of, one of these artillery barrages, and he just stood there. But people all around him were getting hit. One man standing next to him practically got his head taken off, killed. Colonel Smith lost his entire forward observation team, got taken out in that barrage.

“It was during that chaotic situation there where we were taking these very heavy barrages that somebody came in and said Colonel Randolph had been killed.

“I said, ‘Are you sure?’

“He said, ‘Absolutely. I saw him myself.’ He said, ‘I saw the body.’

“So I went outside, ran over to my tank, which by that time had been moved right in back of the C.P., and got on the radio. I called battalion headquarters and insisted on talking to Major Kedrovsky because he was second in command. It wasn’t the kind of message you could pass through channels very well. And we had a very poorly disguised code that we used. Randolph’s code name was George, and the code name for killed was kitten. And we hadn’t used this code very much. I got Kedrovsky on the radio, and I said. ‘George Kitten. Do you understand what I’m saying?’

“And he said, ‘George kitten?’

“I said, ‘Yes. George kitten.’

“He said, ‘Oh.’ It dawned on him.

“And that was it. He left and went immediately to division headquarters and let them know what happened to Randolph.

“If we’d been in a stable situation I would have gone and tried to find the body and find out what happened, but we were in an attack formation, and we had to move out.

“You know, what the attack was all about, the 4th Armored Division drove a corridor up into Bastogne, but they were having a lot of trouble widening the corridor, so we were ordered to attack astride a road that came into Bastogne. And we were astride that road, and over here was sort of a finger of high ground. Then down in the valley you could see Wiltz in the distance. So we were attacking astride this road, we got out of town, and Germans were falling out from the bushes right under our feet, we didn’t even know they were there, surrendering. Most of them were Volksturm troops, old men and young boys, poor guys, you had to feel sorry for them.”

“Did you feel sorry for them at the time?” I asked.

“I felt sorry for the kids. We saw kids that were 14, 15 years old. I really felt sorry for them. The rest of them I didn’t have any great feelings one way or the other, except I saw one guy, one German, up ahead waving a white handkerchief wanting to surrender, and I motioned for him to come, and he starts running down the road, then some GI comes out of the woods, sees him and shoots him. I mean, you hate to see things like that.'

“But we got up a fair distance astride this road. I was with Colonel Smith on one side of the road and I looked back and here comes a platoon of our light tanks barreling down the road real fast. So I stepped out; it’s only then that I remembered that Colonel Randolph told me he might attach a platoon of light tanks to Company B. So apparently he had done it.

“I stepped out and stopped them to ask what they were looking for and they said they were looking for me and Company B, and they said, ‘What are we supposed to do?’

“I said, ‘I haven’t any idea, but I think it would be a good idea if you deployed your tanks along this flank over here,’ because that was wide open — the attack had moved past that, most of the mass of troops were up here and there wasn’t anything as far as this flank goes. It bothered me.”

“That’s the right flank?”

“It’s the right flank. There was a valley; it dropped off very rapidly into a valley, and they did deploy those light tanks there and that’s the last I saw them because I got wounded shortly after that, but somebody told me later that that night the Germans did counterattack and ran right into those tanks. [The story of the platoon of light tanks will be told in my next Substack.]

“We got up maybe a mile out of town; my sense of distance is very poor because we were moving very slowly at times. I’d say at least three-quarters of a mile, and the attack bogged down. The road was curving, and there were some fields here and hills there and the Germans were entrenched, very deeply embedded in both of these strong positions, and these were not Volksturm troops, these were German paratroopers and they were really tough. So they weren’t going to move out. We’d have to move them out.”

“Could you tell the difference, or did you learn that from intelligence?” I asked.

“You could tell the difference immediately in the amount of resistance. I didn’t see any of the Germans, though they had distinctive uniforms as I understand. I didn’t recognize it from that. I could tell from the way the fighting was going, because we were stopped. I had a platoon here and a platoon over here and Bob Vutech was in a reserve platoon that was coming back. There was a shattered building here, and I brought our company train up to that point and had them put the kitchen in that building.”

“When you say a company train, is that a convoy of trucks?” I asked.

“Every company has a certain number of trucks, a certain number of jeeps, halftrack, maintenance halftrack, and I’ve forgotten what other vehicles." And usually you’d have a supply truck with gasoline and so forth. So I got the kitchen set up there and got the gasoline truck there, and Sergeant Schmidt was in charge of this platoon. I told him to send his tanks back. It was about 4:30 or 5 o’clock in the evening on January 9th. I told him to send his tanks back one at a time to get food and gasoline, then come back and send another tank back. The same thing with this platoon over here. This was a brand-new officer in this platoon named Metzger. So it was right about that time I’ve gotten that all arranged and I want to get my 105 tank, which was parked right beside the road.

“I went back to the tank and was going to go back and find Colonel Smith and report in to him to see what was going to happen next. And I put my left leg up on the track of the tank and was throwing my right leg up over the back when this flat-trajectory shell came in. What it was, I heard later, it was a self-propelled gun. I heard the motor start up and I could tell it was moving and it was right after that and the guy fired a high-explosive shell. Apparently there was a double column of infantry moving down the road, on both sides of the road, and that was what he was shooting at. He wasn’t shooting at me. But as I was pulling my left leg up, the shell fragment came in and hit me right in mid-calf. It was still hanging in the flesh; it hadn’t gone all the way through.

“I thought it took my foot off. That’s what it felt like. It seemed to me that the whole shell hit right on my foot and exploded. But you had no time to think. I just, I dived off the tank to the ground on the other side, looked down, and I was very happy to see I still had a foot, and I was lying there, thinking about all this when the heads started popping up out of my tank looking around, wondering what had happened to me.”

“You just dove off the tank?”

“Yes. I went right off the side. I did it deliberately. I didn’t care about the ground or anything else, and it didn’t hurt a bit. It actually felt pretty good to get down.

“I knew I was finished, so I got in the bow gunner’s place in the tank and started back, and ran into Vutech. He was bringing his platoon up, and I told him what the situation was, and turned the company over to him. I went back to the aid station, and about two minutes later they brought Metzger in. He had been shot across the stomach. And that was my last day in combat.

“We were evacuated back to Luxembourg City. I remember going into this operating theater and they had all these operating tables laid out, do you remember the scene in ‘Coma,’ I think it was the movie ‘Coma,’ anyway, it was just one operating table after another.

“Then they operated and the doctor told me there was no reason why the leg shouldn’t be perfectly all right. Then I was put on a hospital train going back to Paris.”

“Were you in pain, or did they give you morphine?”

“Oh, that reminds me. After we left the aid station, they put us in an ambulance. We went in that ambulance from the battlefield to Luxembourg City, and there was one

German prisoner, and there were three GIs and myself being sent back. The GIs were being pretty rough on the German. He spoke very good English, and they kept demanding to know who he was, where he came from, and I remember them pinning him down about, ‘Well, why didn’t you do something about this?’

“He said, ‘I couldn’t. It was the law.’ And that was always the standard answer, and you’re still getting that today, I wasn’t responsible, I was just following orders. I tried to write a short story for Collier’s magazine later based on that incident, but they didn’t take it.

“So then we were evacuated by ambulance to Luxembourg City, then the operation, then the long train ride to Paris, and that’s when it suddenly dawned on me that I’d left behind 30 cartons of cigarettes, and I would never get to Paris with those cigarettes.”

“Had you been due for a three-day pass?”

“I didn’t have one. But all the other officers in the company had had one. I was up next, and I was really looking forward to it.”

“How did you collect thirty cartons of cigarettes?”

“I didn’t smoke. We had a cigarette ration. We had a liquor ration. I used to give each platoon a bottle of whiskey and say okay, as long as I don’t catch anybody drunk on duty, it’s fine. If I ever do you’re never gonna get any more of it. The cigarettes I just hung onto, and they accumulated.

“So I got to Paris, and all I saw of Paris was a dirty window with a bare branch of a tree on the outside. Some great three-day pass in Paris.

“Lieutenant Gaggett and one other guy had heard I had liquor in the tank, as well as the cigarettes, and that night, the night of January 9th, after things quieted down a little they went looking for that liquor. And they found it. It was all smashed up and completely shattered in the bottom of the tank, and that’s when they’re supposed to have sat down and wept.”

Love these stories, it’s amazing to think about what these men went thru. Just think it may have been my father’s Light Tank platoon going down that road.

Merry Christmas

Aaron

Have a great New Year