A French lesson learned

Yet the current regime has no knowledge of their role in the American Revolution

The Putin White House spokesperson recently endorsed the idea of sending the Statue of Liberty back to France while remarking that if it weren’t for the U.S. Macron would be speaking German. Ach du lieber or however you spell it! Given her tender age and blind obeisance to the regime, it likely never occurred to her that if it weren’t for the assistance of the French during the American Revolution, she may well have been dissing Macron with a British accent. It might not have occurred to me, either, were it not for the explosion at Heimboldshausen.

Let me explain.

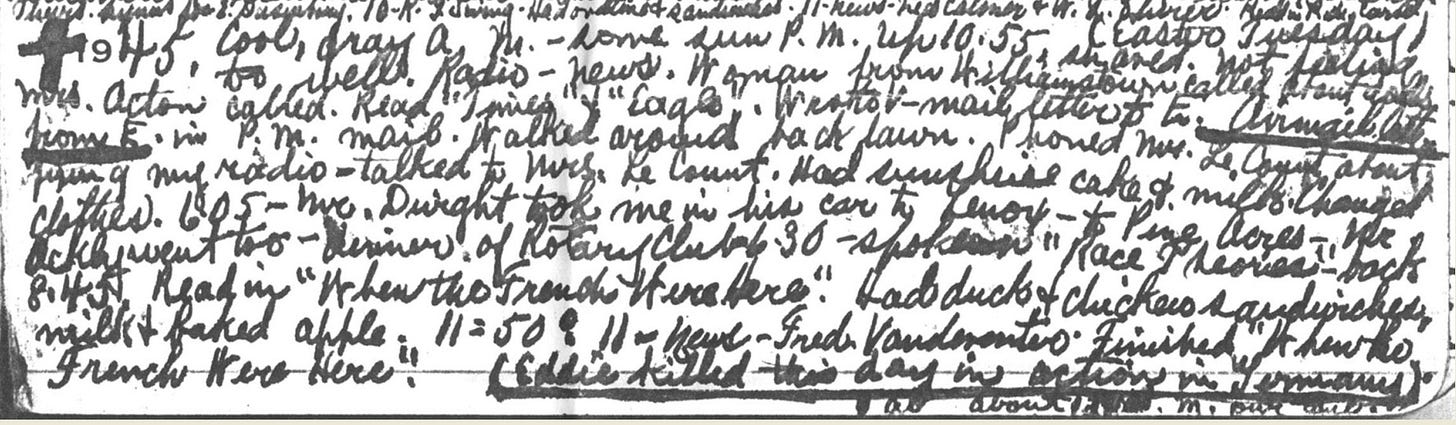

The following picture is of an entry from the diary of the Reverend Edmund Randolph Laine, pastor of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for the date April 3, 1945.

Note that the entry is preceded by a thick black cross, and at the very end is what appears to be a footnote: “Eddie killed this day in action in Germany, at about 12 p.m. our time.”

Eddie was Lieutenant Ed Forrest, the one name I remembered from my father’s stories when I first attended a reunion of his outfit from World War 2, the 712th Tank Battalion, in 1987. As I interviewed battalion veterans, I heard many more stories about Ed Forrest, an original member of the battalion and one of its most respected and well-liked officers, than I heard about my father, who was a replacement and spent only a few days in combat, during which he was wounded twice.

My father said he thought Ed’s father was a minister, and that he might not have approved of Ed going off to war.* In 1995, I thought there must be some record of him in Stockbridge, so I called information — it was still possible to get a live operator in those heady pre-Googular days — and I asked if there was anybody listed in Stockbridge with the last name Forrest. There was not, the non-AI generated human being replied, but there were three in the neighboring town of Lee. She even gave me all three numbers for no extra charge, which I think was free anyway.

I called the first one, Elmer Forrest, because I thought Elmer was a more antiquated name than Dave, Number 2, who turned out to be Elmer’s son. I forget who Number 3 was, because when Elmer answered the phone and I asked if he was related to an Ed Forrest who was killed in World War 2, he replied: “He was my brother.”

“Was your father a minister?” I asked.

“No,” Elmer said. “My father was an alcoholic.”

By now you may be scratching your head and wondering what all this has to do with the American Revolution. I’ll get to that.

“My father knew Ed during the war,” I said, “and he said he thought Ed’s father was a minister.”

“That would be Mister Laine,” Elmer said. He explained that when Eddie was 14 years old (and Elmer was 7), their mother died and Eddie and his father had a big fight; as I recall Elmer may have said that Ed blamed their mother’s death on their father’s drinking. (As it turns out, it was a good deal more than that, but that’s a tale for another Substack.)

Mister Laine, the minister at St. Paul’s, was an “old batch,” or bachelor, Elmer said, and Eddie did odd jobs for him. After the fight with his father, Eddie moved into the rectory.

This is pretty cool, I thought. I asked Elmer if I could interview him and he said sure, just not to come on Sunday until after church. A week or two later I drove to Lee on a Saturday and spoke with Elmer for a couple of hours. I then went to the town’s World War 2 monument and found Ed’s name, and then I went to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The church was empty, but I found an honor roll on a wall, I think it had an asterisk, and next to his name it said “Junior warden of the church.”

In the front of the church I signed a guestbook, and a few days later I called the then-current pastor, Ted Evans. He said he didn’t know anything about Reverend Laine, but that if I called the town historian, the library had a diary that he left.

Initially, I wondered if the minister wrote anything — I was sure he must have — the day Ed was killed. The diary was actually a day book, with a date at the top of each page, and eight or nine lines for each of five years, 1941-45. I wound up photocopying, at 10 cents a page, the entire diary. But for today, let’s stick to April 3, 1945.

The entry is preceded by a thick black cross, the equivalent of an asterisk. Spoiler alert: The reason he announced Eddie’s death in a footnote was because the section for 1945 was at the bottom of the page and he already had written so much that he was out of space. He added it as a footnote because it would be 13 days before the telegram arrived. After all these years and hundreds of times scrutinizing this entry, it only recently occurred to me that the addition of the time must have come much later, perhaps after the minister was visited by an officer (a sergeant from headquarters company, I think) of the battalion. He would have written the original footnote upon receiving the telegram.

But what has all this got to do with the White House demand for Macron to grovel and thank America for saving France’s ass in World War 2?

I’ll tell you what. As I pored through the pages of the diary, I realized the reverend was very well read. He always noted what he was reading, every radio show and commentator he listened to, and how many parishioners showed up for his lectures on Shakespeare. And a lot of his references are researchable on the Internet. Long story short, the last items before the footnote were: At 11 p.m. he listened to newscaster Fred Vandeventer on the radio, and he finished reading “When the French Were Here.”

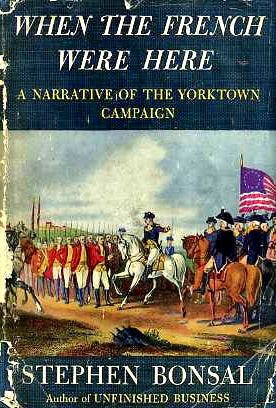

According to his obituary in the New York Times, Fred Vandeventer was a former radio newscaster who originated the quiz show “20 Questions.” “When the French Were Here” was a book about the role of the French in the battle of Yorktown by Pulitzer Prize winning historian Stephen Bonsal.

When the French were here; a narrative of the sojourn of the French forces in America, and their contribution to the Yorktown campaign, drawn from unpublished reports and letters of participants in the national archives of France and the Ms. Division of the Library of Congress

Among the many contributions of the French, and I’m paraphrasing here, prior to the battle of Yorktown General Washington was desperate for money to pay the troops, who were on the verge of mutiny. Knowing that Admiral de Grasse was on his way to America with a French fleet, Rochambeau instructed him to stop in Cuba and appeal to the Cuban people, who apparently had no love for the British. The “ladies of Havana” ponied up an amount that would be equivalent to millions of dollars today, and Rochambeau was able to deliver the funds to Washington.

(As an aside, when the Cuban child Elian Gonzalez was forcibly repatriated in 2000, a Cuban-American columnist in the Washington Times wrote:

The “Havana’s Ladies,” a group of Cuban mothers, heard Gen. Washington’s plea for desperately needed funds and raised an astonishing amount for that time. They sent to Virginia the equivalent in today’s money of $28 million (this figure in a column that appeared in 2000). This has been little exposed in American history books but is well-documented. The inscription that the “Ladies of Havana” wrote on their contribution was:

“So the American mothers’ sons are not born as slaves.”)

Ed Forrest was wounded in Normandy, spent about three months recovering in England, and returned to the battalion in late November in time for the battle of Dillingen and then the Battle of the Bulge, where his tank was credited with knocking out a German tank. Although he was in line to be promoted to company commander, he was outranked by a replacement officer, George Cozzens, so Ed became the Company A executive officer. His duties included setting up company headquarters and finding houses in which to billet the troops. Whether he expected to come home or not, he could not have been in a safer place when he was killed.

On April 3, 1945 — barely a month before the end of the war in Europe — the service personnel — mechanics, truck drivers, crews of a couple of disabled tanks— were setting up for the evening in the village of Heimboldshausen, on the west bank of the Werra River. According to some accounts, during the day there had been sporadic sightings of one or two German planes.

There were several rail cars on a siding, with a wide open field on one side and several houses on the other. Ed chose a fairly strong-looking two-story house, with a concrete foundation, and began setting up his headquarters in its basement. A gasoline truck that was fully loaded with 300 five-gallon jerry cans of gas was parked outside, along with a tank that needed repairs. The gas truck was supposed to hold 250 jerry cans, but driver Joe Fetsch figured out a way to load an extra 50 cans, which made the truck look “like a pregnant cow,” he said.

Heimboldshausen was home to a potash mine (just across the river, in the town of Merkers, was a salt mine that would later be depicted in the movie “Monuments Men,” as it held vast amounts of artworks, currency and gold, including gold teeth and suitcases from victims of the Holocaust).

Most of the rail cars in the Heimboldshausen depot were empty ore-carrying cars, but there were four other cars as well: two boxcars and two gasoline tanker cars. The tanker cars were empty but were full of fumes. One boxcar contained material for making uniforms; the other held bags of black powder for use in artillery.

Around 6 in the evening, somebody shouted “Plane!” A Messerschmitt 109 was approaching the village, flying low over the open field on the far side of the railroad tracks.

Truck driver Joe Fetsch jumped atop the gasoline truck and swung the ring-mounted .50-caliber machine gun toward the plane and was about to start firing. The next thing he knew he was waking up in a hospital two days later.

While I was at the 1994 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division, Ted Hofmeister, one of its veterans, said to me something like, “You’re an author. If there is a mistake in a book, how would someone go about correcting it?”

After he assured me the mistake was not in my book, “Tanks for the Memories,” I asked him about the mistake. It appeared in John Colby’s classic “War From the Ground Up,” which is regarded as one of the best unit histories ever written. In it, he wrote that the carload of black powder in Heimboldshausen was struck by a bomb, causing a massive explosion. It was not a bomb, Ted said, but rather was bullets from a German fighter plane.

In actuality, it was not even the carload of black powder that caused the explosion, but rather one or both of the fume-filled gasoline tanker cars that were struck by bullets either from the ME-109 or the troops who were firing at it. Think TWA Flight 800, the commercial plane that exploded over New York Harbor, after which an exhaustive investigation determined the explosion was caused by a spark in an empty center fuel tank, although there are some fairly convincing arguments/conspiracy theories that the plane was struck by a missile. Nevertheless.

The explosion in Heimboldshausen demolished four houses directly opposite the tracks and blew the roofs off many other houses in the town. The railroad tracks themselves looked like someone took a corkscrew to them.

The house in which Ed Forrest had just set up his headquarters in the basement collapsed. Sergeant Ervin Ullrich, a cook who had just finished preparing a hot meal out in the open for the men, was killed and the meal sent flying. Despite the intensity of the blast, the gasoline truck did not explode, as virtually all of the damage was from the concussion. Wilson Eckard, whose grave in North Carolina has been adopted by my friend Kaye Ackermann, was among three other members of the tank battalion killed.

*I’m not sure what gave my father the impression that Ed might not expect to come home. I don’t believe Reverend Laine was disapproving; in fact, as it turns out, Laine was a chaplain during World War I and was either wounded or gassed, and took pride in displaying his memorabilia. Ed also proposed to his girlfriend, Dorothy Cooney, before going overseas. Dorothy never married.

Great history! Aaron has a nack for finding and telling the most interesting WWII stories in an interesting and sometimes humorous approach! Love it!

What a great story!!