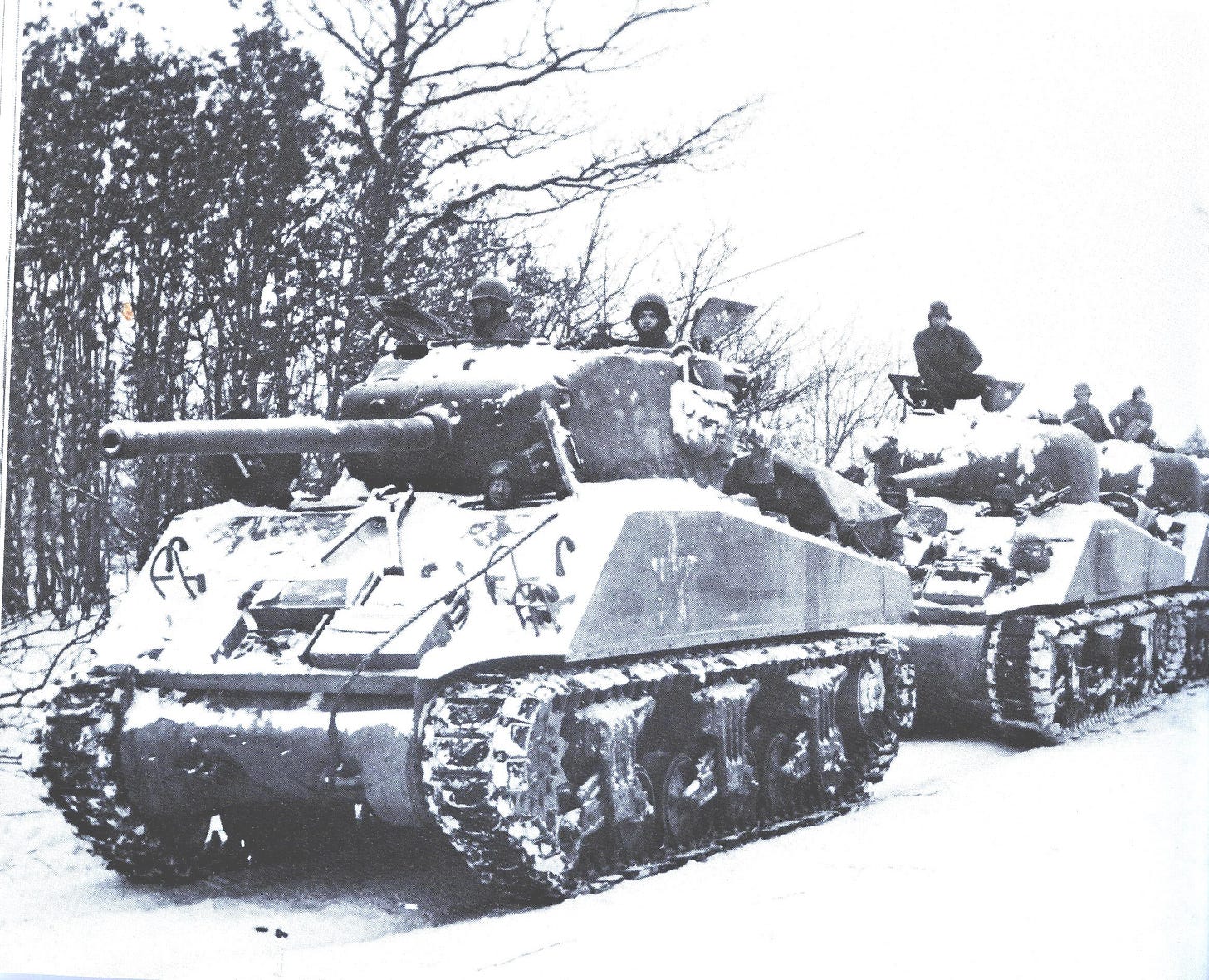

I tend to overuse the word “iconic,” but as long as I can remember, I’ve been describing the above photo, of a column of tanks heading into the Battle of the Bulge, as iconic. Until recently, though, I had no idea just how iconic it was. The tanks were in A Company of the 712th Tank Battalion, and although there are four tanks in the photo there was a fifth in the column, making for a platoon at full strength. I knew that the driver in the lead tank was Dess Tibbitts, because when I interviewed him at his home in Orland, California (I still have an iconic mug from the Weed Diner on Route 5 where I stopped for coffee while driving north from San Francisco), he had a blowup of the picture in which he was more recognizable. And I knew that the lieutenant in Tibbitts’ tank, Wallace Lippincott, would be killed a few days later. I also knew that the tank commander practically standing in the second tank was Sam MacFarland, who answered my query to the newsletter in 1987 by inviting me to the battalion’s reunion, but whom I never got to interview. I knew that the position of the tankers indicated they were in a non-combat situation. And at some point I learned that the tank commander visible in the fourth tank was Sergeant Hank Schneider, who, like MacFarland, would receive a battlefield commission (promotion to lieutenant) and would be killed by a sniper the day he received the commission.

The photo most likely was taken on January 8, 1945. I was able to surmise this from the battalion’s after action reports:

On 6 January at 1530 (3:30 p.m.) company left Remeling with Battalion on the march to Luxembourg. It arrived following morning (7 January) 0330 (3:30 a.m.) at Noerdange — distance 63 miles. At 1300, 8 January, company moved to Boulaide, Luxembourg, arriving at 1700 (5 p.m.) Move was made in heavy snowfall.

Think about this: 63 miles on January 6 in what history has noted was General George Patton’s famous march to join in the Battle of the Bulge, highlighted by the 4th Armored Division’s relief of Bastogne, where the 101st Airborne Division and elements of the 10th Armored Division were surrounded. (Coincidentally, the 712th Tank Battalion originally was part of the 10th Armored Division before being broken out as an independent battalion.) The distance from Boulaide to Bavigne (population 176) is about 25 miles, so if the photo was snapped on January 7 it would have been the middle of the night when they were in the area, making the daylight picture more likely.

Getting back to the picture, Philip Eckhart, a loader in the platoon (that might be him above Dess Tibbitts in the first tank, although it might also be the gunner), kept a diary in which he described the march:

“It was on the 6th of Jan., on Saturday, that General Patton gave orders for the 90th to make their secret move up into Belgium and help in the Bulge,” Eckhart wrote. “The roads were really icy, and the snow was really coming down. On one hill just before getting into Luxembourg, we had to go down in five-minute intervals. Several tanks went off the road, but no one was hurt. On one hill our tank slid into a tree, and I hit my nose on the .30-caliber machine gun. We backed up, and before we got by we hit that tree three times. A little farther down the road we went off the side, and our track nearly came all the way off. When the driver backed up and pulled on the right lever, I was very much relieved to see it going back on.

“It was pretty late when we caught up to the rest. They had already reached the town and were getting ready for bed. It was three in the morning and we slept in a café, on the floor. There were about 15 of us in there, and it was pretty warm. The woman made us coffee, and we had a nice drink before going to sleep. The next day was Sunday the 7th of Jan. and we had steak for dinner. The snow was really coming down, and it was about nine or ten inches deep.

Incidentally, Eckhart refers to Patton ordering the move to be kept a secret. At one of the earlier reunions I went to a veteran told me the 90th Infantry Division, which was at full strength after having a couple of weeks to regroup after withdrawing from Dillingen, was to cover their insignia and markings and possibly even trade them with the 28th Infantry Division, whose positions they would be replacing, so that the enemy wouldn’t know they were facing a fresh division. Of course, the veteran said, as they headed north into the Bulge, Axis Sally came on the radio and said “Welcome to the 90th Infantry Division.”

If you’ll notice, the star on the lead tank appears to be smudged, which might be a result of such an order.

The driver of Sam MacFarland’s tank was Corporal Roy Sharpton of Glencoe, Oklahoma. He would be the first tanker in the picture above to be killed, but he wouldn’t be the last.

“It was Friday, the12th of January,” Phil Eckhart wrote in his diary. “As we were going through a field, we met about two thousand prisoners coming back. We stopped there for a while and got out of the tanks. All of a sudden the Germans started to throw in the artillery, and we made a dash for our tanks. One of the shells hit just as I was going in, and I heard the assistant driver call out. The concussion knocked him down. His hatch was open, and when they had quit he made a dash for it. Not very far from there had been a mare and her colt walking around a haystack. When we came out they were both laying there dead.

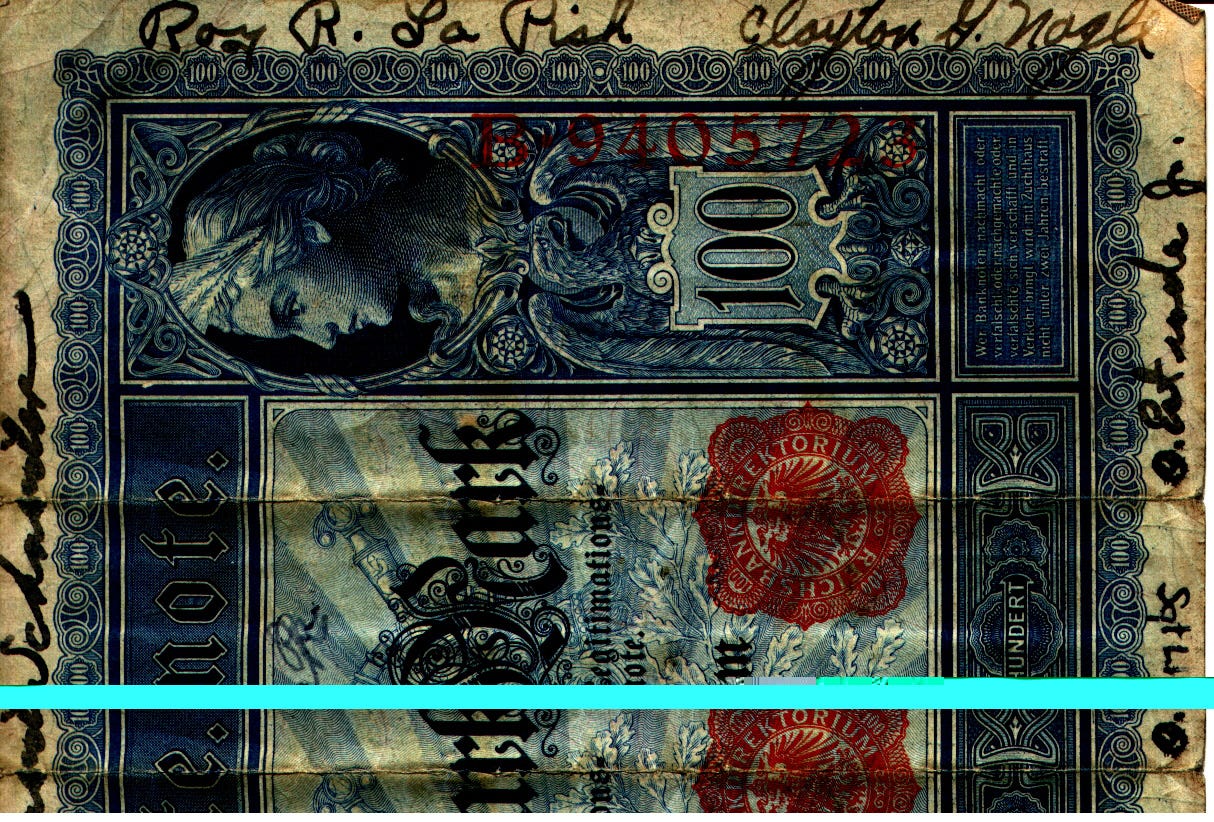

“About three tanks behind us the driver and an infantry lieutenant were hit. The tank driver was Roy Sharpton, and he died later on. We asked the captain how he was, and they said he was improving. Next thing we knew he was dead. I have a ten dollar bill out of my first Army pay, and one of the names I have on it is his.”

“We were standing outside of our tank,” Dess Tibbitts said, “and we heard them shells coming over, and you know, the one that hits you you don’t hear it. And I ran and jumped in the tank and jerked my hatch down and just before I jerked my hatch I saw him (Sharpton) go to the ground. About that time a jeep drove up, reached out and got him, and that was the last we saw him. And the next day or two it came out that he was dead. Usually you didn’t get the results that quick but we did.”

In one of the tragic ironies of war, according to Tibbitts, during a lull in the battle of the Falaise Gap a few months earlier, Sharpton had climbed into the gunner’s seat, a position he was not familiar with, possibly just to see what it was like, and accidentally fired a burst of three to five rounds from the .30-caliber machine gun, killing Duane Miner in the next tank.

There’s an interesting bit of true crime history associated with the picture as well. Charles Vorhees, who is not in the photo but was the driver of MacFarland’s tank, transferred into the 712th after delivering a light tank to the battalion during the battle for Dillingen just prior to the Bulge.

When the orders came to move into the Bulge, Vorhees said when I interviewed him in 2001, “I went with the maintenance tank. Before we got into Luxembourg, we were going up some mountain, got pretty close to the top and that tank turned completely around. We had to go clear to the bottom again. It was a blizzard there the day we moved up. In fact, when we got into Belgium, there were two of us walking out in front of the tank trying to find the edge of the road for him to follow us.

“But we were only up there about two days when they put me in MacFarland’s tank. His driver got hit.”

About three years ago I got a call from two podcasters who were preparing a program on what was the pre-O.J. crime of the century, the Brach candy heiress murder, and they wanted to know if they could use material from my interview with Charles Vorhees.

As that interview was winding down, I asked if he had any siblings. He said he had a sister. And then he said she disappeared.

She disappeared?

Yes, he said.

Sandwiched between the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby and the trial of O.J. Simpson, a strong candidate for the Crime of the Century was the 1977 murder of the Brach candy heiress, Helen Vorhees Brach.

Charles said his sister was a coat check girl who married the founder of the Brach candy company, makers of candy corn for Halloween, jelly beans for Easter, chocolate covered raisins and a slew of other treats, including nonpareils, which were one of my favorites growing up. Her disappearance has still not been officially resolved, although a man she took up with following her husband's death was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder, sentenced to 30 years in prison, and was released in 2019 at age 87. He has since passed away. More about this in a future Substack. I don’t know if the podcasters ever completed their project, but thank you google, or maybe it was bing and I was only using google as a verb, that’s kind of ironic, isn’t it, using bing to google something, but anyway, it turns out American Justice did an episode about the case of Helen Vorhees Brach as recently as April 25 of this year!

Now, back to the picture.

Quentin “Pine Valley” Bynum, who gave my father a lift to the front in Normandy, was driving one of the tanks. Lieutenant Lippincott, although it doesn’t appear to be painted anywhere on it, wrote to his wife, Elizabeth, that he had named his tank Beanie after a small dog the couple had adopted. After he left, Beanie was struck by a car and killed, not a good omen.

For a bit of perspective, here’s a passage from the battalion’s unit history:

On 12 Jan., after outposting at BOULAIDE and HARLANGE, A Co., with 358 (the 358th Infantry Regiment), moved up through C Co. The 6th Armd (6th Armored Division), striking east with exposed flanks, was pointing toward BRAS. If juncture could be effected there, a large enemy force would be entrapped. A Co., moving through SONLEZ, was chosen to effect this mission, and soon was locked with the strongly resisting Heine in a two-day slugfest. Finally two tanks, braving devastating anti-tank fire, grasped the other side of the important railroad tracks and joined with the 6th Armd, thus sealing off large Heine forces.

But the individual tankers knew little more than what was going on around their platoon.

“Next morning, which was on Sat. the 13th of Jan., we were to go and get some prisoners in a barn,” Phil Eckhart wrote in his diary. “We started down through the field, and there were three Germans running towards the woods. My .30-caliber had jammed, and the gunner asked me if the 76 was loaded. He fired a high-explosive at them, and hit one of them square. Well, you can imagine what happened to him. We went on down to the barn, and found out there was nothing there, so we started back to where we had been. When we went back we were in the rear, and could see that the Germans were firing at the tanks ahead. They hit us in the rear on the right side and knocked out our motor. I was sitting in the turret with an H.E. [high-explosive] in my hands, but it did not take long to get rid of it and get out. They kept throwing armor-piercing at us, and I was glad it was not H.E. Later on the driver went back to pull the fire extinguishers, and to shut off the master switch [This was Tibbitts]. While he was leaning in to shut off the switch, the Germans took a piece of the gun off right over his head with an A.P. (armor piercing). Later on, he was put in for the Bronze Star; that gave him one cluster.”

In a letter to his wife dated January 4, 1945, Lieutenant Lippincott wrote, “I have been getting very little mail from thee lately [the couple, from Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, were both Quakers] and about all the letters that did come through are quite old as they have been the salt water address. Today the mail situation was a little bit better, and although I did not receive a letter I did get a Christmas package from thee. The candy that was in the package sure was delicious. It did not last more than 15 minutes around my crew. The package contained Krispy Krunch, a Peanut Chew, Baker’s chocolate bar, and a lot of small gifts which I had a lot of fun unwrapping. It made me sort of homesick, though, because all I could think of was all the mess of wrapping paper that we scatter all over the floor on Christmas day after all the presents are opened. By the way, I don’t believe I told thee but I no longer refer to my tank as Beanie. I may be superstitious but after Beanie’s tragic end I don’t want this big tank of mine to have a tragic end. I now refer to it as Lizzie. And I feel certain that being named after thee it will have lots of luck and bring all of my crew back.”

As his crew was sent back to get a replacement tank, Lieutenant Lippincott took over platoon sergeant Hank Schneider’s tank.

“Next day, which was on Sunday, the 14th of January, the crew all but the lieutenant went back to get a new tank,” Eckhart wrote. “Our gunner got the projectile that knocked us out. I don’t know if he took it home with him or not. When we were on our way back to the company in the ammo truck, our own planes started to bomb and strafe us. We got out and ran in an old building. The fellows were firing at them with the rifles on their peeps, and some were firing at them with M-1 rifles. Later on we found out that they thought the Germans were still in the town, as there was a lot of German vehicles knocked out.

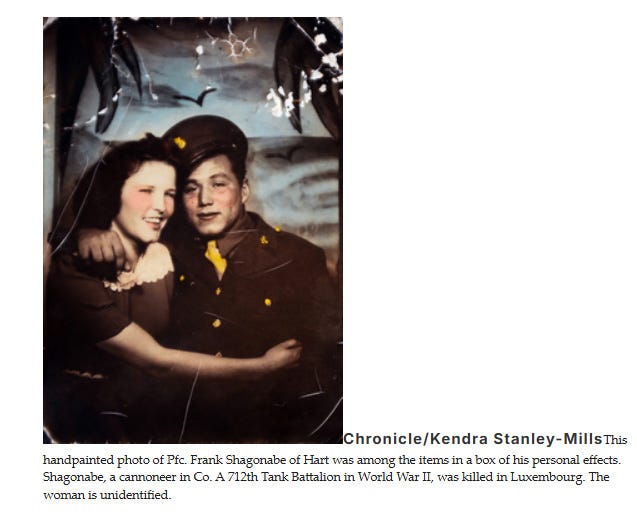

“We got back to the company and slept in a barn that night. Next morning we got the sad news that our Lieutenant and two other men had been killed that night. When our tank was knocked out the Lieutenant took No. 4 in the lead, and they had orders to take a woods in the night. Well, you know that a tank is not very good for night fighting, and when they pulled out the Germans were waiting for them with six anti-tank guns. They hit the lead tank, and killed the driver, loader and tank commander. If I had not been knocked out before I would have been the loader in that tank. The driver was Quentin Bynum, the loader was Shagonabe, and the tank commander was Lt. Lippincott. The gunner was Roy R. La Pish and the assistant driver was [Hilton] Chiasson. That was the fifth tank he had been knocked out of. Him and Roy stayed back for quite some time, then they sent Roy back up later on but Chiasson never went up again. They kept him back, and he worked in the kitchen.”

“On Monday, the 15th of January, we took a tank way to the rear to have ordnance work on it. Tuesday they came and got the driver, Dess Tibbitts, and told him he was going to Paris on pass.”

Thank you for sharing this.

War is a terrible thing, but at the human level it is more tragic and terrible still.