Anatomy of an Anomaly

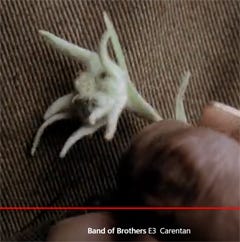

What's an Edelweiss doing here?

“Don’t go.”

Although I read Stephen Ambrose’s “Band of Brothers” soon after it was published in 1992, I only now am watching the mini-series, despite having referred to it often while describing my books. But when the Tom Hanks-Steven Spielberg production came out in — holy cow! I just asked Bing when it came out and the first episode aired on HBO on Sept. 9, 2001! — in a video clip on YouTube, there was a dead German soldier in Normandy and he had an Edelweiss in his lapel. I noted then that it seemed out of place. Now, how is it that I, a self-taught, fledgling historian, would pick up on a detail like that? Glad you asked.

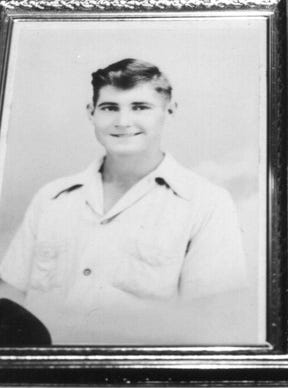

When I first went to a reunion of my father’s tank battalion, I met twin sisters Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten. The twins were 16 years old when their brother Billy, 18, was killed. Over the next couple of years, I heard and read several accounts of the battle in Pfaffenheck, Germany that claimed the lives of Billy and three other members of C Company’s first platoon.

One day there was a note in the 90th Infantry Division newsletter saying there would be a ceremony in Pfaffenheck on March 16, 1995, marking the 50th anniversary of the battle. I told Paul Wannemacher, the battalion secretary, I’d love to go, so he wrote to Johann Seeliger, the contact person listed in the article. Johann wrote back and said I would be welcome to attend; however, there was something I should know: The ceremony was being hosted not by the village, but by the German veterans who fought there. And those Germans were in the Waffen SS.

“Don’t go. You’ll only humanize them,” my supervisor at the Bergen Record, Kathy Sullivan, said when I told her what I planned to do with my vacation.

In his letter to Paul, Seeliger, wrote that he himself owed his survival to the fidgety nerves of an American tanker who took five shots point blank at his machine gun position and missed. Paul, being a tanker, got a big kick out of that. (Seeliger was captured at Wingen, prior to the battle at Pfaffenheck. In a memoir he wrote under a pseudonym, his description of the capture, the first blast of which shattered his machine gun and wounded him, is considerably more terrifying.)

Sergeant Byrl Rudd, a veteran of the battle, wrote in a letter to the battalion newsletter that the SS troops at Pfaffenheck were “fanatical.” Francis “Snuffy” Fuller, the first platoon lieutenant, wrote in a letter to the twins that after the battle, 90 dead Germans were counted.

When I met Seeliger, I asked him about the description of his unit as fanatical. He said they were fanatical not to Hitler but in their devotion to one another after three years of fighting the Russians in Finland and then the Americans in Alsace-Lorraine during Operation Northwind. He said they knew the war was lost.

Pfaffenheck is in the Rhine Moselle Triangle, a little south of Coblenz. The 90th Infantry Division, to which the 712th Tank Battalion was attached, crossed the Moselle River on March 14, 1945, and the remnants of Seeliger’s 6th SS Mountain Division North were assigned as the rear guard to buy time while other German units retreated across the Rhine.

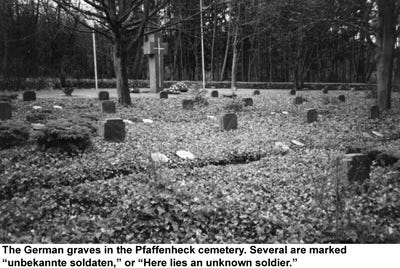

Kathy was right, in that I did humanize them, but only if you consider them having been subhuman to begin with. It certainly was not my intention to humanize the entirety of the SS, many of whom committed atrocities. The reason for the ceremony in Pfaffenheck, where the 6th SS gebirgsjagers, or mountain troops, gathered annually, was that 100 members of their unit are buried in the village cemetery, a figure consistent with Lieutenant Fuller’s account of 90 Germans killed. Many of the graves were marked “unbekannte soldat” (unknown soldier), and some of those with names indicated the deceased was between 17 and 19 years old.

On the day of the ceremony it rained, and a protest the veterans were expecting failed to materialize. One of the monuments was dedicated to the anti-tank battalion, which made me feel a little funny when a wreath was laid at its base. I thought of Billy Wolfe’s last words to his sisters when he was home on leave: “So long kids, and if I never see you again goodbye.”

Billy Wolfe

Seeliger, a retired environmental lawyer, had a decal of an Edelweiss in the window of his BMW. When I asked him about it, he explained that it was the symbol of the “gebirgsjager” because it only grows on mountains above the tree line, at about 10,000 feet. In “Band of Brothers,” it was worn by a “fallschirmjager,” or paratrooper, and one of the Easy Company soldiers says that in order to be allowed to wear it, a soldier had to climb the mountain and pick it himself, and that it was “the mark of a true soldier.”

That’s how I came to sense something was amiss about an Edelweiss showing up in Normandy. Not that it couldn’t have happened; the paratroopers, like the alpine troops — the American 10th Mountain Division would be the equivalent — were elite soldiers.

I arrived a day early in Pfaffenheck and spent some time with two German veterans who also were at the guest house early. Both were captured at Pfaffenheck. One of them, Fritz Gehringer, took me to see the tree he was hiding behind when he was shot five times, by hollow point bullets. The other said that many replacements in his outfit came from the Luftwaffe and were referred to as “Goering’s gifts,” because there were not enough planes so they were used as infantry.

So far I’ve watched four episodes of Band of Brothers. In the next newsletter I’ll discuss the episode I refer to the most, Bastogne. Thank you for reading. I’ll be happy to answer any questions in the comments.