And then this happened

A smwargasbord of history

So much is going on that I should be addressing: the 79th anniversary of the February 19-March 26 battle of Iwo Jima; the March 4th 80th anniversary of the first daylight bombing raid on Berlin; the impending 79th anniversary of the March 16 Battle of Pfaffenheck; the seventh episode of Masters of the Air, a veritable smwargasbord of history. And then this happened.

I opened my email.

An order form from the Kassel Mission Historical Society was forwarded to the board members noting that a customer ordered a $15 digital download of the Kassel Mission Reports, a bargain at twice the price. The purchaser’s name was not familiar, so board Chairman Jim Bertram wrote and asked if he had a connection to the mission.

This is the response:

Hi, Jim-

Thanks for following up on my purchase. I'll give you my overly long story. My uncle, known in 1944 as Constant (or Constantine; your website lists him with that name) Galuszewski was flight engineer/top turret gunner on Lt. Donald Brent's B-24 "Eileen" for the Kassel Mission. (Our family later shortened our Polish surname, but my father chose Gale and Uncle Connie chose Galus!).

Like many WW II combat veterans he never talked about his service. I was probably a teenager before I learned that he had been shot down and became a POW, and I knew virtually nothing beyond that fact. In 2001 my son was doing a school assignment which involved contacting a military veteran to thank them for their service and to let them know he was praying for them, so I suggested he contact his great uncle. In response he received a copy of a photograph of the crew of Eileen (the same picture as on your website), and a letter of acknowledgement. Uncle Connie passed away a few years later, and I filed my copy of the photo and letter away.

Having read the book “Masters of the Air” when it was first published I, of course, began watching the mini-series, which caused me to think about my uncle and prompted me to do some research. The only information I had, which was included in my uncle's correspondence, was that he was a B-24 crew member shot down over Kassel and that he was in the 702 B.S. [Bomb Squadron.] With the internet, Google, Wikipedia and your web site [kasselmission.org], I was quickly able to learn all about the mission and my uncle's involvement. I am now moving on to try to learn more about his service — when did he arrive in England, how many missions did he fly on, etc.

I do have one question regarding the website. On the page "The Brent Crew" there is a footnote that says George Linkletter saw Galuszewski at Stalag Luft 1, but Linkletter was KIA. Is it perhaps Lt. Walter E. George who saw my uncle there, since he was held at Stalag Luft 1? I also know my uncle was in contact with Walter George after the war since the photo my son received says “Courtesy - W.E. George”.

Sorry to be so long winded, but this has been quite a journey for me, and it is exciting to be able to preserve some of our family history. Thank you also for preserving this information on the website.

Paul Gale

That’s all it took. I flashed back to 2001, in a Mexican restaurant in San Antonio, Texas. The 90th Infantry Division was having its reunion in San Antonio. Walter Eugene George either lived in or had a connection with a university in Austin, he was a professor of architecture, so I thought I might be able to meet and interview him. I would have made a side trip to Austin but he graciously offered to meet me in San Antonio.

I dug out my transcript of the interview, all 18 pages of it, and forwarded it to Jim Bertram with the suggestion he forward it to Paul. I figured if his uncle was on the Brent crew he would have been on some of the earlier missions Eugene described. But the most significant part was his account of the Kassel Mission.

Eugene George was the co-pilot, Donald Brent the pilot.

Now imagine you’re Paul, and you’re learning the details of your uncle’s time in World War II and this shows up in your inbox [this is actually just an excerpt]:

Eugene George: I knew there was communication trying to get some fighters in close to us, and I also remember our tail gunner saying, “There are fighters coming in from the rear.”

And I said, “Oh, well that’s great.”

And he said, “They’re not ours.” FW-190s.

So I knew they were approaching from the rear. Of course I didn’t see any of this. …I was very much aware of the fact that we were under fire, and what made me aware of it was our own guns started firing. The German artillery was sort of like patters of rain in the cockpit. Our own guns were making much more noise than they were, but my concentration was right on that wing. I was totally locked in to keeping the aircraft in formation. I knew we were being hit, but the first, see, I was flying the airplane and I was aware that we were dangerously hit when one of the engines started, I was watching engine instruments and I thought the engine was burning, which it was, and I could see the engine right next to me was burning, and I didn’t know if I should put the fire extinguisher or not. I didn’t, and Brent was still just sitting there. He sat through the whole mission and yet he wouldn’t fly, but we were losing power, and so he did that, and I pushed the bailout button, or the emergency button. I gave the crew time enough where I thought they would bail out and go through the procedures that we had learned when leaving the aircraft.

I did try to raise the rear of the airplane and the front of the airplane on intercom, and I couldn’t get anything from either direction. I knew we’d been hit; I didn’t know whether something had happened to them. I could see flak coming on the nose of the airplane because it was in front of me, and the Germans were approaching from the rear, coming up, rolling over and split-S and down, coming out. I saw one of them do this when I was getting the top turret gunner out.

After I gave him enough time to get out, I could see in the cockpit area. The radio operator and the engineer, the top turret gunner, were supposed to leave on the sound of the alarm, open the bomb bays, and we would keep on flying the airplane until they got clear, then we would go out. I went out and the top turret gunner was, whose name incidentally was Constant S. Galuszewski, he was from East Tonawanda, New York, and the radio operator was named Sam Weiner, who was from the Los Angeles area. But Galuszewski was still in his turret, and I had to crawl up there and jerk him by the seat of the pants. Weiner didn’t even have his parachute harness on. So I jerked Galuszewski out of the turret, but in doing that I saw the German plane turning and splitting-S. After having made his run, a beautiful airplane, very very close, as close as to the other end of the, half, well, three-quarters of the way to the other end of the room. And I got Weiner’s harness and shoved it at him, and opened the bomb bay door, I mean I opened the door into the bomb bay, and it was just a mass of flame. The fuel gauges which were on the left, they were spitting like blowtorches, and the bomb bay doors of course were closed and we would have been trapped if they had remained closed. And they operated hydraulically. There were fires all over the place in the bomb bay. It’s amazing, I’d see areas of flame chasing up pipes and pipework, things like that. And the switch to open the bomb bay doors was right between those two blowtorches which were the fuel gauges. I thought I could hit that switch if we had hydraulic power, I could open the bomb bay doors. If we didn’t, I’d have to wind it, and I didn’t think I could survive in the flames. But I could jump through all of this flame on the catwalk to get there, and I hit the switch on the way over to it, and I jumped through and got there. And the bomb bay doors opened.

But I still had the responsibility of these two enlisted men. So I went back through those blowtorches. Galuszewski was just sort of standing there in a daze. I started snapping Weiner’s harness on him. Everybody had chest packs, I had a back pack. I’d been off oxygen for a while to do all of this, and I didn’t know but what my parachute was burned when I walked through the fire. So I walked through the fire and I walked back through the fire.

While I was standing over Weiner and getting him put back together, Brent came by and told Weiner to hurry up and he went ahead and bailed out. And he went ahead and went through the door into the flaming area. I never knew whether he went back to check on people in the waist or whether he went on out or what happened. Or whether he was injured in going out, because the fire obstructed vision, I was concerned about that. But he went on out. I still got Weiner put together, ready to go, and and Galuszewski, and they were behind me, so I went on out. And they went on out too, as the aircraft broke up. It broke up. They told me later.

But the three of us were the only ones who survived of the crew.

Aaron Elson: Brent didn’t survive?

Eugene George: Brent didn’t survive. I never knew what happened to him. During the reunion at Bad Hersfeld, I heard what the Germans did and things like that, but the Brent story is another story which I’ll fill you in on down the line. Now, do you want the account of my fall, of my jump?

Aaron Elson: Oh yes! I’m spellbound.

Eugene George: I came out of the airplane. I used to swim a lot, and I came out, I was afraid I would hit some obstruction and my safest bet would be to get into a cannonball position. I didn’t know whether I had a parachute or not, by that time. And there were two things, three things. One, I’d been off of oxygen for quite a while, and I was concerned about this. I wanted to get lower. Two was, I knew there were a lot of German fighters in the area and chances are they wouldn’t shoot someone in a parachute, but I was afraid of even getting rammed, or run into, by a fighter. We had been briefed on the fact that the Polish fighters in the RAF would have no hesitation shooting a German in a parachute, and that we knew when this had happened and the Germans would retaliate even, that’s what we’d been told; I don’t know if there’s anything to that or not. But the other thing was, in training films, we had a Navy character named Dilbert, did you ever hear of Dilbert?

Aaron Elson: Just the cartoon.

Eugene George: He was a cartoon. He was a cadet, or a pilot, who goofed every possible way. One of these cartoons showed Dilbert in a parachute with a target painted on his chest and a duck sitting on his head and a Japanese aircraft lining up his sights, and I had that vision, of Dilbert. Those three things. And, uh, I was tumbling, and I thought, in the cannonball position, I thought I’d better get out of that, and I didn’t know quite how to do that, and I stretched out into a swan dive. And I reached for my ripcord to see if everything was still there, and I started spinning, so I got back in the swan dive.

There was a solid cloud cover underneath us. I thought when I get into those clouds, I will pull my ripcord.

I went right through the clouds, and I could see the ground. But I was still in a freefall situation, and then I thought, well, if people would see me from the ground I [would get captured]. This was somewhere between 750 and 1,200 feet. I didn’t need an altimeter to judge heights at that low altitude, and I was curious as to whether I had a parachute or not of course, but actually, the swan dive situation, it’s almost exhilirating. It was fun!

So I fell most of the 23,000 feet, and I pulled my ripcord, and I was jerked up into the proper parachute position. My parachute worked! That was the great news. And I was coming down on some trees, which I later found were beech trees, I was coming down in a wooded area, and my canopy covered the top of a tree, and I was swinging in the tree.

I was kind of reconnoitering, even then of course, I could hear an air raid siren, and I could hear impacts of aircraft crashing. And as part of this I could hear a lot of small explosions which I think were ammunition on the aircraft.

I was able to swing over to the trunk of the tree and I discovered that my boots had snapped off when the parachute opened.

Aaron Elson: It happened to George Collar. Probably five or six people I’ve interviewed had their boots snap off from the jerk of the parachute opening. And I’ve seen that in many individual instances, that people who had never jumped out of a plane before, that’s one of the things that happened to them

.Eugene George: Now I don’t know what sort of a religious person you are, but in the tree, I got over to the trunk and could climb up so I could reduce my parachute, which I left in the tree, and while I was in the tree I looked down and there were two foxes. They were beautiful. Red foxes with white tips on their tails. And they were obviously frightened by all of this activity. I thought, they would know where to hide, I mean they would go to a dense place. And so I watched their direction. I never saw them again, but I got on the ground and headed in that direction, and I did get into a very dense undergrowth. I could see the sky but I was pretty well concealed, and sort of took stock of things.

I opened my escape kit, and it had been rifled. The stuff that mostly [was left] were some hard candies, some halizone tablets for water purification, and the map was not there, which was really the one thing I wanted.

Waitress: Coffee?

Eugene George: Yes. I would like a cup of decaf, black.

Aaron Elson: Regular.

Eugene George: I had a little pocket Bible, and with it a New Testament with psalms, and I just opened it up, it was about ten o’clock in the morning, and it fell open to the 91st Psalm.

Aaron Elson: Is that “May ten thousand fall to your left...”?

Eugene George: Yes, that’s the one. So, that was very reassuring. That was a miracle. I mean, the foxes and the psalm. I waited for quite a while. I did see three, they could not see me, but ME-109s flying low over, they were in formation, probably returning to base. Also, there was a path not too far away and I heard some people talking. There were three men, all senior citizens of sorts, and they had a little fox terrier dog with them, and I was really worried about that. But I was downwind from them. I was enough of a Boy Scout to know about this sort of thing, and the dog never caught me, but they were sort of talking to the dog, the dog was looking up at them, they went right on by. But my plan was to walk all day, head for Switzerland, I mean walk all night and sleep all day, and before the sun came up I would find a place to dig in.

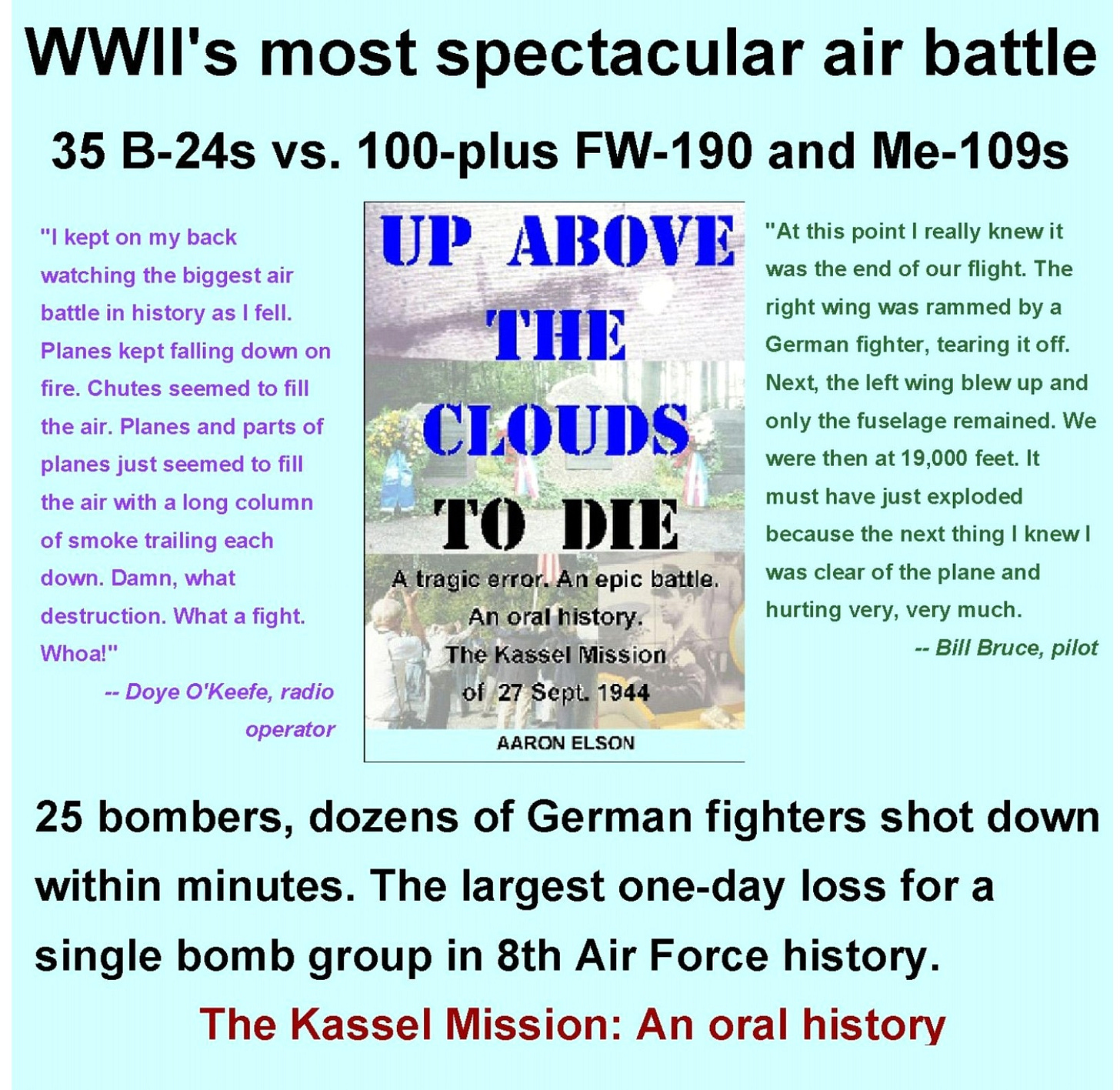

There’s more, although I don’t remember if we had dessert or not. I also have Sammy Weiner’s written account in my book “Up Above the Clouds to Die.

A couple of my friends have sent me their comments via email. It would be better to leave a comment by clicking on the link. When creating a Substack I have to make all kinds of adjustments and it might say “comments for paid subscribers only,” unless I adjust it so anyone can comment. I might have overlooked that previously.