Drinking in the sights

A lieutenant's five days in the City of Light

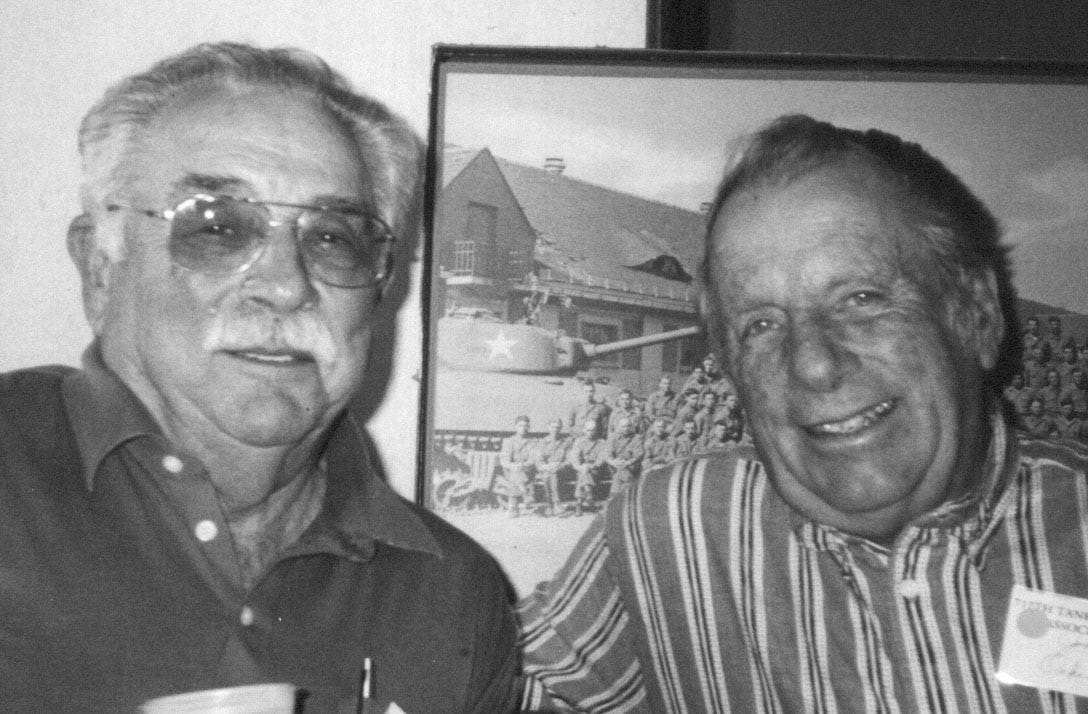

At the 1996 Pittsburgh reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I sat down with Dan Diel and John Ockenga of B Company. Diel, a sharecropper’s son from Kansas with an eighth grade education, was one of 14 sergeants in the battalion who received a battlefield promotion. Ockenga was a mechanic in the company. Both were veterans of the 11th Cavalry, which traded in its horses for tanks as part of the fledgling 10th Armored Division, from which in 1943 the 712th was broken out as an independent battalion. Diel was wounded in Normandy, was awarded a Silver Star, and received a battlefield commission. The following is an excerpt from my work-in-progress, “Tales of Love, Food, Booze, Jumping Out of Airplanes, Meeting General Patton and Winning World War 2,” a curated collection of themed stories and anecdotes from my oral history interviews.

Dan Diel: I was a sergeant pulling a platoon leader’s job from February till the end of the war, but I didn’t get the [lieutenant’s] bars until the end of May, the 25th of May, and the war had been over for two or three weeks. I’m sitting there counting points, the hell, I’m going home. Old timer, I’ve got gobs of points. [Sergeant] Bennett was still there at that time, I don’t remember if he come in or if he sent a runner, but I went to the orderly room, anyway, and Bennett says, “Get your shit together, you’re going up to division tomorrow to be discharged and sworn in as a second lieutenant.”

“The hell I am. I’ve got points, I’m going home.”

“[Captain Bob] Vutech come out, and he says, “You ain’t got anything to say about it. Patton’s name is on them orders, that’s the way it’s gonna be.” And he was right.

John Ockenga: You did the duty, you might as well take the bars. You didn’t get the pay, though, did you?

Dan Diel: Not until you got the bars. Then, after I got the bars, we was there at Amberg, and I didn’t have any uniform. Nobody really had dress uniforms, it was just more or less field uniforms, and I didn’t even have any officer’s stuff at all. I was running around with enlisted shirts with the bars on them. But that went on for, clear up until the middle of July, and I don’t remember whether it was [Colonel Vladimir] Kedrovsky or Vutech that called me and said, “You’re going to Paris and spend your money.” Because when you get a commission you get a $250 clothing allowance, and I had no opportunity to spend it. There was no officer’s clothing stores anywhere around. So they had to send me clear to Paris to buy a uniform. And I was in Paris on Bastille Day, on the 14th of July.

They sent a truckload, a 6-by-6 truckload from Amberg, and the first day you went to Frankfurt and spent the night. Then the next day you went from Frankfurt to Luxembourg. And you had a layover. And then you got on a train en route from Luxembourg to Paris. So you took off on Friday morning, you got into Paris Sunday afternoon, and your pass started at 6 o’clock at night. And it went through 6 o’clock Monday, 6 o’clock Tuesday, 6 o’clock Wednesday you had to be back on the truck, on the train going back to reverse that. And you got back into camp Friday night. So you left on Friday morning, the following week on Friday night you was back in camp.

Well, there was another young lieutenant from the 90th Infantry that was on that same trip, and so we got to drinking champagne, and we drank a bunch of it. Well, this was, when Wednesday night rolled around and everybody else is heading for the train to go back, we told them, “Have fun. We’ll see ya.” We took off, and we went AWOL. For two days. And they went and caught the train and reversed the trip. And we went out that night and got drunk. I mean we poured one on. Just drunker than hell off of that champagne. We got up, and we had to give up our bed. When you registered in at these government-controlled hotels, you had to have a pass for those three days, and that’s all you could reserve that bed for. Well, there was guys in there from another outfit that come in that had rooms reserved for another two or three days after ours, and some of them had longer passes than we did. Anyway, he says, “Hell, just come up and pull the mattress off, and we’ll sleep on the box springs, you sleep on the floor.”

Fine with us. So we went out and we got drunk. We come in and pulled the damn mattress off and slept on the floor and the next morning got up and oh, god, was we sick. And went out and spent the day, and that night, why, we took on a little more, but we didn’t get drunk like we did the first night. And Friday morning, woke up with a hell of a hangover. And we were still going to a officer’s mess to eat. They never checked anything; they didn’t give a shit, if you went in and flipped them a quarter or fifty cents or whatever it was for a meal, why that’s all they wanted. And we woke up that morning and said, “Well, it’s Friday, do you think we ought to think about heading home?”

“Well, it probably wouldn’t hurt for us to get back.”

So we’re wandering around in Paris without any pass; if somebody would have demanded it, we couldn’t show them a pass that was legal. So we go out and flag down some MPs, and “How do you get out to Orly airport?” And they told us and we went out, and got a damn GI ride out to the airport, and went into the operations office and told them where we wanted to go.

“Well, just go out there, and there’ll be, every plane that comes up they’ll announce where it’s headed for and when you get one going where you want to go, why just go and ask them for a ride.”

Pretty soon, why, they called one that was going to, oh, what in the hell is the name of the town that was about 30 miles from there, where they had the ... Nuremburg! There was a plane that was going to Nuremburg, and that was, I told him that we ain’t going to get anything closer than Nuremburg. That’s 30 miles. So we go up and ask the pilot, he says, “Yeah, but you’d better get on early because I’ve got a full crew. If you want a seat, just go ahead and somebody else’ll have to sit on the floor.”

So we went in and got on the plane, and pretty soon they come out and they’re sitting there looking around. Well, one of them had a nurse with him that they’d picked up somewhere, and they was gonna fly her back, and they had to make a detour to drop her off. And they dropped her off, and then went on to Nuremburg, and we got in there, these guys that was in the detail that they were flying, they took off across the field somewhere. Then this pilot come over, he says, “You guys got transportation?”

I says, “No.”

He says, “Did you eat?”

“No, we haven’t had lunch.”

“Well, we’re going up to lunch. Come on, we’ll go up and eat, and then when we get through, we’ll get you a ride.” So we went up and ate, and we got through, why, he had a driver, and he told him what part of town to go into, and he dropped us off. And we hadn’t stood there five minutes and one of our own trucks come by, and we flagged him down and got on and was back in camp in the middle of the afternoon, and got cleaned up, well, we never really got dirty, but we went in and went to eat, and when we come back, why, here’s this truck come in with those guys that had been on the truck all day. All haggard. And Kedrovsky comes walking along, he was headed for the Officers Club when I was headed for the barracks. He says, “Diel. Wasn’t you in Paris?”

I says, “Yes sir!”

He says, “I didn’t know they got back.”

I said, “I don’t think the rest of them did.”

He questioned what happened. I said, “Well, we flew.”

And he just grinned, and he says, “I can always depend on those old cavalrymen,” or something like that.

John Ockenga: We pulled some capers over in Mexico, didn’t we?

Dan Diel: Before the war. Before Pearl Harbor, you put on a pair of Levis, and ditched your uniform, well, everybody had civilian clothes, and you put on civilian clothes and you could cross over into Mexico, but you had to be out by midnight.

John Ockenga: And that Blaha got locked in the damn thing over there, he got drunk and passed out in the (unintelligible). I was in the orderly room at that time, on duty, he called in, he says, “Get me somebody over here and get me out of here.” He says, “I’m in the jug.”

Dan Diel: Do you remember Farris?

John Ockenga: No, I didn’t get into Paris.

Dan Diel: Farris. Corporal Farris.

John Ockenga: Oh yeah, yeah.

Dan Diel: Big tall redheaded guy. And he was a dingaling. One time I was on charge of quarters and there was a phone call come in that the border patrol had spotted a bunch of Mexicans that was coming out of Mexico crossing the, and it was in the winter, and there was snow on the ground. So they said to get somebody and they designated Farris to be the squad leader, and they used one of those portee trucks, they called them, it was a semi trailer that they could put eight horses and men in and their saddles and stuff and haul them out across, and when they got to where the truck couldn’t go any farther, then they’d unload the horses and take off across country. He went out and rounded ’em up and took ’em back into Mexico, but he didn’t stop when he got to the border. He took ’em right on in, and I said, “Jesus Christ,” you know, taking a damn armed patrol into Mexico, and the relations weren’t too good at that time anyway.

And then that summer before we went to Georgia, they had a ball team, and they went over to play the Mexicans in Tecate, and after the ballgame was over they were drinking that Tecate beer and catching burros and riding them around, and they figured there was gonna be an uprising over there and they had to send a damn rescue squad down there to bring the ballplayers back before they got through.

John Ockenga: Oh, we had a good time.