(If this newsletter is truncated, please click on “view entire message”)

It seemed like Easter is a little early this year, so I asked google when Easter was in 1945 and it turns out it was March 1, only a day later than this year’s holiday.

World War 2 was winding down by the beginning of April, flowers were blooming, trees were growing leaves, windows were sprouting white sheets, but somebody forgot to tell the 712th Tank Battalion that the fat lady wasn’t quite ready to sing.

In Stockbridge, Massachusetts, though, the mood was anticipatory; the Reverend Edmund Randolph Laine, pastor of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, noted in his diary on April 2 that a parishioner called to discuss plans for a “celebration of the end of the war with Germany.”

Meanwhile in Germany on April 2 Dick Bengoechea, a 19-year-old son of Basque immigrants from Boise, Idaho, had what decades later he believed was a premonition.

“Looking back,” he said at the 1995 reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, the first one he attended, “I think I knew something. I was an assistant driver, and the day before, they rode up and said ‘You’re driving today.’ And every time I pushed on the clutch, my leg was shaking. I was like hey, why am I so nervous today?

“The day before that, we were in another little village, the sun came out that morning and we were standing in this little street against a building, and I had been on guard duty all night. I was standing there in the sun, half-asleep, and all at once I looked out across this little valley, and here’s a Kraut with his hands in the air. No weapons or anything. ‘Kamerad! Kamerad!’

“We wheeled him in, all of us were standing on both sides of the street, and he said, ‘There’s an 88 zeroed in on the street,’ but they never fired it. And we panicked getting the hell out of there. We buttoned up in our tanks and moved on out of town. But I think I knew something real bad was gonna happen. I didn’t have any focus.”

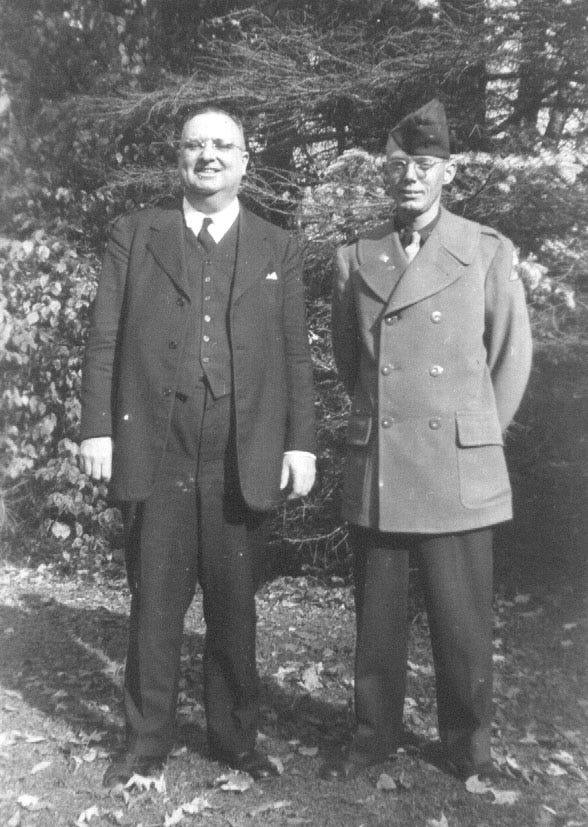

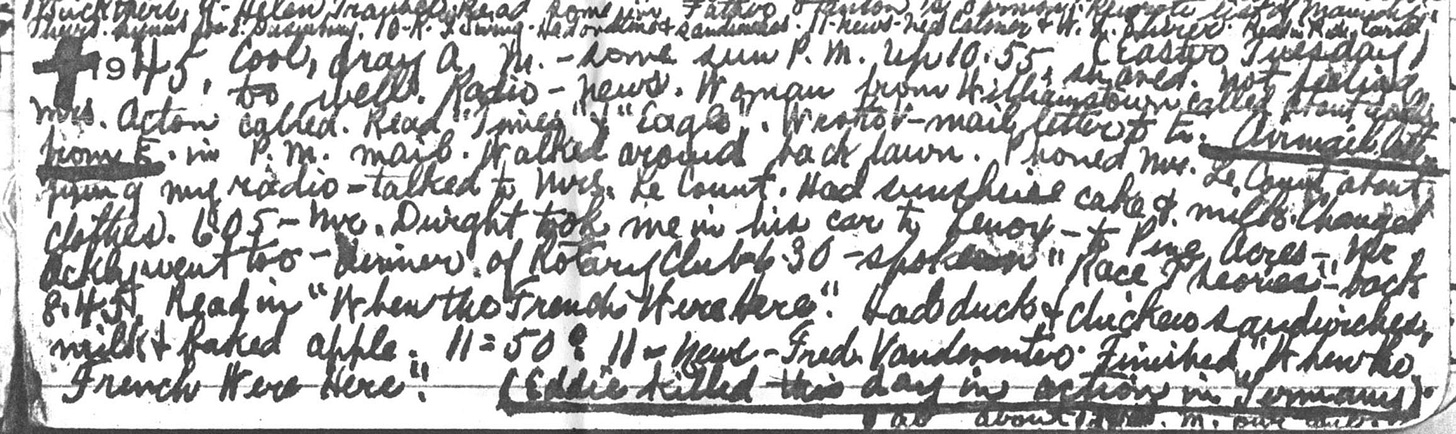

Reverend Laine noted in his diary that April 3, 1945 (Easter Tuesday) was cool and gray in the morning, with some sun in the afternoon. He woke at 10:55 a.m. and was “not feeling too well.” (The minister was a chaplain in World War I and was either wounded or gassed, possibly both, resulting in frequent minor illnesses). He noted that he read the New York Times and the Berkshire Eagle, as he did most days. He wrote a “V-mail letter to E.,” which, due to lack of space in the journal, was short for Edward L. Forrest. When Ed was in his teens he did odd jobs for the minister. Following the death of Ed’s mother and a falling out with his father, whom Ed blamed for his mother’s death, the minister, who was not married, took Ed into the rectory and raised him like a son.

In Germany, Joe Fetsch, who worked at a service station in Baltimore before the war, drove a gasoline truck in Service Company of the 712th. Delivering gas to the front “was a little hairy,” Fetch said. “When it got too hot, they’d run me off. They’d say, ‘Get that damn gas truck out of here.’ All you’d need was a piece of shrapnel to hit one can, and I’m sitting there with a two and a half ton truck, no canopy or no top on it, three hundred cans, five gallons apiece, about 1,500 gallons of gasoline, and just one little piece of shrapnel and I’m sitting on dynamite.

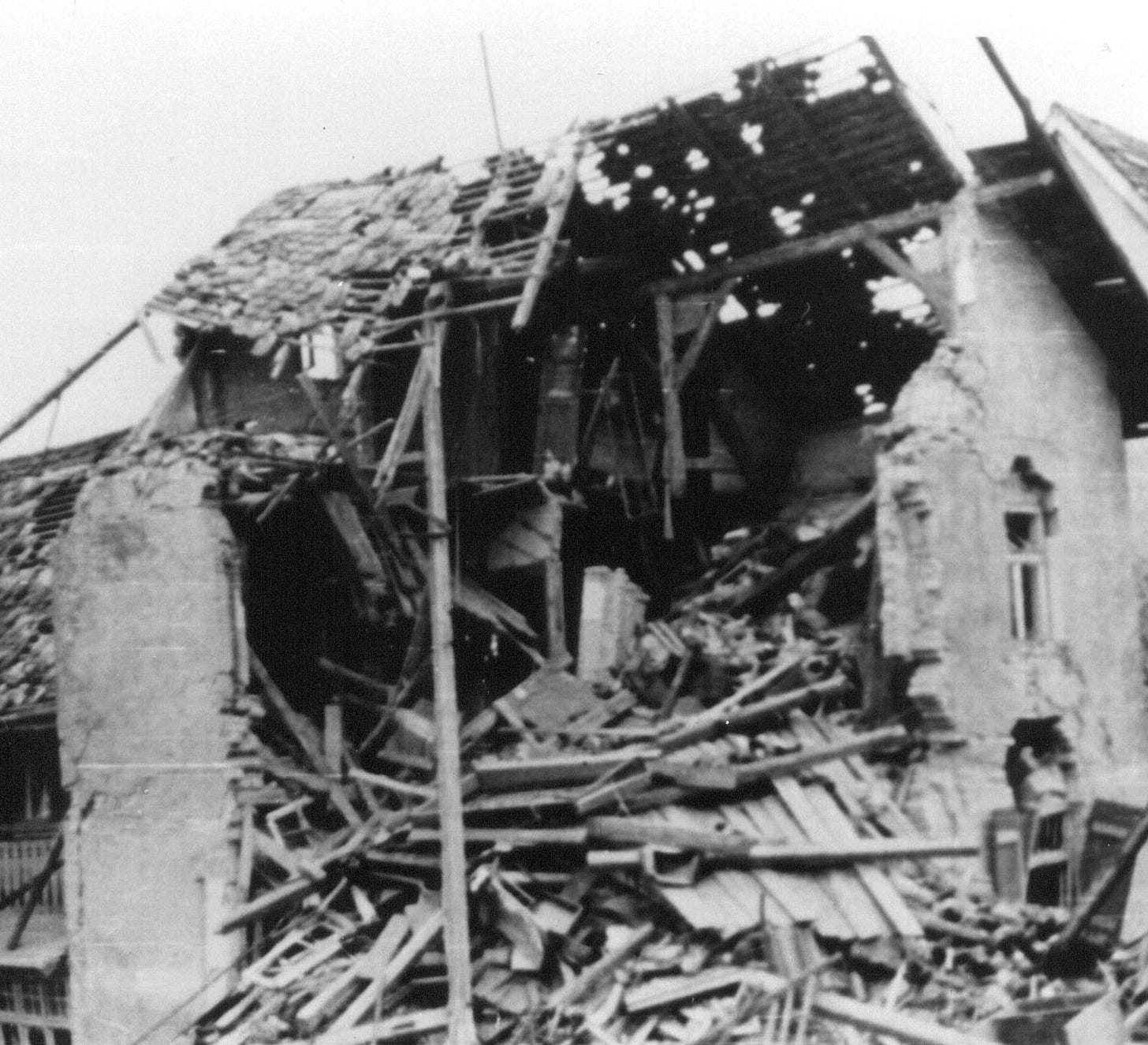

“In fact, when A Company's headquarters got blown up, my truck got demolished. Actually, it didn't burn or blow, but a building fell on it. A plane had been following us all day. There were two empty tank cars in a little railroad depot, and two boxcars with black ammunition powder in them that we didn’t know about. They were trying to flush a few Krauts off the hill until they sent a tank around and some infantry, and this airplane that had been following us all day came back and started strafing, and somebody hollered ‘Here comes a plane!’”

Either bullets from the plane or the soldiers firing at it “hit the ammunition cars and the tank cars and blew everything, the whole town,” Fetsch recalled. “I think there were 32 of us in that area, and out of 32, there were only four guys able to move.”

The explosion, in the village of Heimboldshausen, on the Werra River, claimed the lives of five members of the 712th and wounded more than 20 others. There also were many casualties among 90th Infantry Division service personnel.

In Stockbridge, an airmail letter from Ed arrived in the afternoon mail on April 3, Reverend Laine wrote. He took a walk around the back lawn of St. Paul’s, and made a phone call about having his radio repaired. In the evening he spoke on the subject of “Race Theories” at a dinner of the Rotary Club, and finished reading “When the French Were Here,” a book about the role of the French in the American Revolution.

“Our tank was broken down,” Dick Bengoechea said at the 1995 reunion, “so one day we’d ride either in a tank or we’d ride with the company 6-by-6. That day we rode with old Fetsch. [Joe, an original member of Service Company, was a few years older than Bengoechea, who joined the battalion as a replacement]. He says he remembers somebody hollering ‘Here comes one now!’ That would be me. “I said ‘Here comes one of them sonofabitches now!’ And he backed the truck up against that building.”

The gasoline truck had a ring-mounted .50 caliber machine gun, “but the rollers were rusted,” Bengoechea said. “It wouldn’t roll. So I had a can of oil. I was standing on this running board, and a guy by the name of Fred Hostler was with me. We were working on the rollers, and then I turn around and look right up this valley, and it’s just like in the movies, this plane was coming in. I could see the bullets coming down, and I don’t remember, from this point. I woke up pinned under the truck covered by all kinds of shit and I couldn’t get out.

“And Hostler, somehow he either got blown out, or got out of the truck, and in this house on this side was a window, with glass in it, and it exploded. It cut him; he couldn’t see worth nothing, just like a meat grinder. I’ve never found him since. He’s in Pennsylvania, but he’s never responded, and when we ran into each other in Paris a few days after that in the general hospital there, the only remark he made, he said, ‘That little girl blew up.’

“There was a little girl standing in that window. He was gonna dive into that building from his side of the truck. But that’s all he ever said, and I thought, well, maybe he’s a little rummy yet.

“I didn’t see the little girl because I was on the other side. But I woke up, and I couldn’t get loose. I hollered, and he crawled over, and he couldn’t see. He rubbed the stuff off of me, and got me out of there. And somebody said the aid station is up here.

So I guided him, and he dragged me up to the aid station. They gave me morphine from there, and I don’t know a thing until the next morning. I woke up when an American nurse in a field hospital said, ‘Wake up, we’re sending you to Darmstadt, and then you’re gonna fly to Paris.’ In a C-47. And there was Purple Heart pinned on the pillow, with the citation.

“Then they gave me another shot and I woke up the next day in a Paris hospital. And it was a day or so after that I ran into Hostler. We were both in wheelchairs, and he was going down the hall. Of course we knew goddamn well we weren’t going to be up front for a while, so we greeted each other, ‘Heil Hitler in case we lose.’ And this major came in and said, ‘You assholes.’ He was really shook up. But we made a big joke out of it. That’s the last time I saw Hostler. But Fetsch ended up there as well.

“I was injured all over the face and head,” Fetsch said. “I didn’t have a steel helmet on, and I had a knit cap, backwards, one of these damn ol’ Army knit caps, and everything came down on my head, and a steel girder came in behind my legs and held me up, or I’d have been under that rubble also. And they tell me, I don’t know how true it is, when they came and found me, they dug me out and I was saying my legs are broken, and this John Clark, who’s here today, he said, ‘We ran you for three city blocks before we caught you,’ and I don’t even remember coming out of that rubble.”

On April 4, Reverend Laine attended the monthly meeting of the Stockbridge Library trustees and wrote an account of the meeting for the Berkshire Eagle. That night he listened to radio newscaster Fred Vandeventer and the Herald Tribune News, and read in the Virginia Historical Magazine (this likely was the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, the quarterly journal of the Virginia Historical Society. Fred Vandeventer, according to his obituary in the New York Times, was the radio newscaster “who originated the radio and TV quiz show “Twenty Questions”).

It was very windy and there were snow flurries in Stockbridge on April 5. The reverend wrote a V-mail letter to Ed and, among other things, visited a parishioner who had scarlet fever. In the evening, he noted, he listened to Raymond Swing. (When I first came across this name in his journal, I assumed it was a music program on WQXR; only after an Internet search did I learn that Raymond Graham Swing was a popular radio commentator.) On April 6 he read the Berkshire Eagle, the New York Times, and the Converted Catholic Magazine, a publication, according to the online books library, for Protestant converts from Catholicism.

On April 7, the minister noted, he “began to write Airmail letter to E.” when he was “interrupted by phone from New York from Gertrude Robinson Smith — saying that her mother had died.” (This was a pretty big thing as Gertrude Robinson Smith was the socialite who would be largely responsible for the development of the Tanglewood cultural center in the Berkshires.) In the next few days there would be a flurry of activity preparing for the funeral.

On April 8, Reverend Laine wrote a “V-mail letter to E. (No. 1106)” (He apparently kept a running tally of his correspondence since Ed was drafted in 1942). At 3 p.m. the repairman “came to fix radio — after working at it — decided to take it home. Over to E’s study in Par. House to get E’s radio.” The repairman “came over & detached it & put it up in Study (1st time in E’s Study in one and a half years.)”

It’s 1996 and I’m at the annual reunion of the 90th Infantry Division, seated at a table in the hospitality room with copies for sale of my book “Tanks for the Memories.”

“You’re an author,” one of the veterans said. “Do you know how I can go about correcting a mistake that’s in a book?”

I sure hoped it wasn’t my book. Luckily it wasn’t, although my first edition was not without its share of errors.

The explosion at Heimboldshausen had found its way into “War From the Ground Up,” John Colby’s history of the 90th Infantry Division, which, if you can find a copy, is one of the best unit histories ever written. Colby wrote that a German fighter plane had dropped a bomb, when, the veteran said, it was a boxcar full of black powder that caused the explosion.

I, too, bought into the veteran’s boxcar of black powder theory, which is the version given in the 712th Tank Battalion’s unit history, “Well Done.” It wouldn’t be until 1999, when I visited Heimboldshausen, that I learned from a German historian that it was bullets striking not the boxcar of black powder but one of the gasoline tanker cars, which were empty but filled with fumes — think TWA Flight 800 which exploded off Long Island, New York, when a spark ignited fumes in an empty center wing fuel tank — that caused the explosion. (That also was the reason Joe Fetsch’s gasoline tanker truck didn’t explode, because it was concussion, not fire, that caused the damage.)

But by a bit of serendipity, I had another eyewitness to the explosion, and I seized the opportunity to get his story.

“I was about 200 yards away,” the veteran said, “and I saw the German plane go out of control. He hit a house about four or five miles up the road. And we left town because the whole town was mashed. And as we were leaving, we saw the German 109 up against the side of a building, smashed.”

At this point, I asked the veteran his name.

“Ted Hofmeister,” he said. “I was in Headquarters Company of the 358 [the 90th Division’s 358th Infantry Regiment]. I heard the planes. There were two, a P-51 chasing an Me-109 [when I visited in 1999, the historian Walter Hassenpflug, who met me there, explained that it was actually two Me-109s, but the trailing fighter peeled off after the lead plane crashed].

“I saw the explosion,” Hofmeister said. “Half of the sky was red. The railroad station was flattened. There wasn’t anything left of it. The buildings across the road from it were occupied by Germans, and I don’t know how many of them were killed. A whole bunch of us went up there and started rescuing these people. They were buried under rubble. And when we got up there, we saw an old man — I say old man, he's probably younger than I am now — and he was trying to lever up a staircase that had fallen on his wife's legs. He had a timber that was eight or nine feet long and he was trying to do it, but he wasn't strong enough. So about four big guys took hold of the timber and they pried it up, and when they did another fellow and I reached in and grabbed her under the armpits and pulled her out. And while we were doing this she was praying in German and telling us what good solders we were and she kept patting me on the arm. It wasn't until later I found out the whole sleeve of my field jacket was bloody, because she had cuts all over.

“We rescued her; they got her on a litter and took her away, and we went on to the next building, and it was occupied by about three families. And the first thing we discovered when we went in, there was a landing, and there was an old lady, maybe 80 years old, she was about half buried in the rubble, and all that was sticking up was her arm and one side of her face. And her arm was going up and down, spasms. And we dug her out, put her on a litter. I have an idea she died.

“We went up to the next door and a woman came running up to us and she started talking in German, which I can understand a little bit, and she said something about her baby, it had been blown out of her arms. We looked all over for that child and couldn't find it. We figured it had been blown out the window and been buried under the rubble.”

OMFG, I would have thought if textspeak had been invented by then, this veteran just corroborated what Dick Bengoechea said about Freddie Hostler saying a baby was blown out the window. He wasn't rummy after all.

"And we rescued about ten kids," Hofmeister said. "I particularly remember one boy, about 12 years old, he had his nose pushed way over to one side of his face; he had a broken arm, all cut up. All the people were cut up. And we went on to another building to see what we could do, and about that time one of the men from our company ran up and said we were evacuating the town because it was so shattered, and so we loaded up, and that was the last I saw of it."

"How many men were in the rescue party?" I asked.

"I'd say about thirty," he said. "About five minutes after the explosion, one of our fellows, a big Swede, he took his helmet off and was wiping his forehead, and some of the tiles fell from a roof and hit him on the head and knocked him out. We had I'd say roughly 60 men, not of our company, but from different companies, about 60 men were injured. I didn't even remember that the tankers were in the town. All I remembered was that the 358th Infantry was there. I don't know that anybody in our company got killed. I know quite a few got injured. As a matter of fact, one fellow, even after the war was over, from occupation duty, it was about three months after this, and they were still picking glass out of his face.”

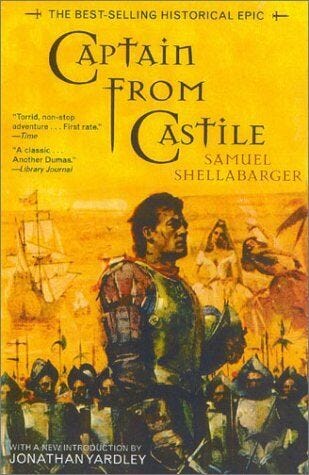

The weather began to warm up in Stockbridge on April 9. It was 77 degrees at 2 p.m. and 78 degrees at 4. Reverend Laine wrote a V-mail letter to Ed, and wrote a “press note for VE Day” and had it delivered to the Eagle. In the evening he listened to the opera singer Marian Anderson on the radio and began reading “The Captain From Castile.”

April 10 was cool early, “40 degrees,” but “warmed up” to 80 degrees and sunny at 2. “Two V-mail letters arrived from E. (written Mar. 26 & 29). At 1:15 he went to the cemetery for the “Committal Service for Mrs. Robinson Smith.” He wrote a V-mail letter to Ed and “dusted desk & other things in Study.” On Wednesday, April 11, he celebrated Holy Communion, and wrote in parentheses (for peace). In the evening he listened to “News - Harry Marble & Quincy Howe from Western Front & Bill Costello. 7 - Fulton Lewis,” and read some more in “The Captain From Castile.”

“Look at those railroad tracks,” I said to Harry Moody at one of the reunions of the 712th. Joe Fetsch was supposed to make the gasoline run on April 3 but Harry took his place because Joe drove the day before. We were looking at a photo taken by Jack Roland, an officer in Headqurters Company who became a professional photographer after the war.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” Harry said. “Up on the hill, they were twisted just like you’d taken your hands and twisted it. Section after section, and parts of rail cars. Evidently he hit an empty gas car. It was in a rail yard on the other side of these houses. I tell you, when we came into where we was gonna spend the night, it was in the early afternoon, me and Margolski was to take ammo and gas to the tanks. We threw our bedroll, turned around, and as we were going toward the tanks, I seen the boys run for the antiaircraft gun."

"You saw them?"

"I seen ’em down in the valley. So I told Margolski, I was in front of him, I said ‘There’s somebody after us.’ So we got down, and there was the biggest boom I ever heard. I never heard a bomb make that much noise. And that's when that plane come in and strafed all those cars, and the explosion.

“When we got back, Margolski wanted to know, ‘Where are we supposed to stay?’

“I said, ‘We were supposed to stay in these houses here.’ Flat. Brick houses. Just flat. So when we got down to investigate, why, there’s 20, 22 people we lost right there. Joe Fetsch was one of them. And I didn’t see Joe no more until he come out of the hospital. But those houses were flattened out, and rail cars, tank cars, and the rails were like just if you had taken your hands and twisted it. When that plane strafed that village, they shot that plane down and it went into that barn. It burnt the barn of course. Those Germans were digging this pilot out of the remains, and they was putting them in a basket. And I noticed his boots still burning, and that was about the biggest portion of him that was left.”

Thursday, April 12, in Stockbridge was warm and foggy in the morning. Reverend Laine notes that he “wrote V-mail o letter to E. (No. 1111). He wrote a press notice for Sunday’s sermon and read in the Eagle. He went to call on a parishioner and returned to the church at 5:45. At 5:50, he “turned on Radio (WABC) - heard news of death of Pres. Roosevelt.” He began preparing a Memorial Service for the President. In the evening all radio programs were off, “replaced by news about late Pres.”

Friday, April 13, was hot and sunny, 84 degrees. The minister listened to the News and Memorial Services for President Roosevelt. In the afternoon he went to the Library Annex to check on the notice for the next day’s Memorial Service. On Saturday, April 14, he wrote, “Heard the terrible news of the death of Tommy Burt on the Western Front.” He made some phone calls and wrote an Airmail and a V-mail letter to Ed, and made some notes for the Memorial Service. At 4, he noted, “Memorial Service for Pres. Roosevelt — choir sang — large cong. — made address — over 4:55. He put some clippings in Ed’s Airmail letter and mailed it on the way to South Lee, where he “called on June Burt & the Burts — great sorrow.” At 8 p.m. he went “over to church to the rehearsal of Te Deum for VE Day. Later, he “made out program of Memorial Service for T. Burt.”

On Sunday, April 15 (Easter 2) Reverend Laine rose at 7:40. On the News he noted, “heard 90th Div. (E’s) was near Czecho-Slovakia - 13 miles.” he went to South Lee for a “Special World Wide Service,” and returned at 10:05. At 11 he used the Special World Wide Service at St. Paul, and “Spoke of Tommy Burt.” At 4 he listened to the NBC Symphony Orchestra on the radio, and his housekeeper, Jessica French, brought up a “V-mail letter from E. (written April 1).

At 8:20 p.m. on Monday, April 16, 1945, Reverend Laine wrote in his journal, while reading the New York Times, “phone from Gr. Barr. Tel. Office of message that E. was killed - April 3 - wire arr. 9.”

The minister’s diary entry for April 3, 1945, is preceded by a thick black cross, added 13 days later, and a footnote: “Eddie killed this day in action in Germany at about 12 p.m. our time.