Mabel Bynum of Stonefort, Illinois, was a mother of five boys and two girls. “We were a farm family in southern Illinois,” her son James Bynum said. “When my brother Hugh was five years old he fell off a horse and broke his right arm badly. The doctor said, ‘Mae, I’m going to have to take his arm off,’ and she said, ‘No you’re not.’ She was Mabel Claire Murphy Bynum, and she had a tongue that could equal that of a muleskinner.

“And he said, ‘But the bones are sticking out.’

“She said, ‘I’m not going to have a one-armed son. You fix the bones and the arm the best you can, and it will grow.’ And by damn it did. She was that kind of person.”

When her son Quentin was a few months old, he came down with diphtheria, although James speculates it might have been the Spanish flu as the year was 1918, and that same doctor pronounced him dead.

Mabel would have none of it and barred the door, refusing to let the doctor leave. So he told her to warm the baby by the fire of the cookstove, James said, and he was soon revived.

“Outside of that, none of us had ever been particularly sick. We were a very poor, very healthy family.” Three of the brothers were over 6 feet tall, including Quentin, who was 6-3 or 6-4, James recalled.

When I first went to a reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I learned that my father twisted his ankle jumping off a tank before he ever got into combat. The next day the platoon he was supposed to lead as the lieutenant was sent on a mission without him. His platoon sergeant, Jule Braatz, told me that my dad wanted to catch up to the platoon so he hitched a ride to the front with a tank driver whose nickname was Pine Valley. Pine Valley told Braatz that when my dad got out to look for his platoon, he was wounded by shrapnel.

“This is third hand information,” Braatz said, “because Pine Valley was later killed.”

Pine Valley was Quentin “Pine Valley” Bynum.

Soon after I launched my first web site in 1997, I got an email from Quentin Bynum’s nephew, Chris Bynum, who had inherited his uncle’s dogtags and said Quentin was his hero. Soon I was out in Springfield, Missouri, meeting Chris and his dad, who was Quentin’s younger brother.

Mabel Bynum died in 1951, James said, “and we all feel that she died of a broken heart. When Quentin died, we would go by sometimes; she had a big cedar chest in which she kept her mementoes. And she had his flag, and his medals, and pictures of him in there. And we would go by once in a while and surprise her sitting in her bedroom on the floor with that flag on her lap, crying. And my mother never cried. She was just a stouthearted old gal.”

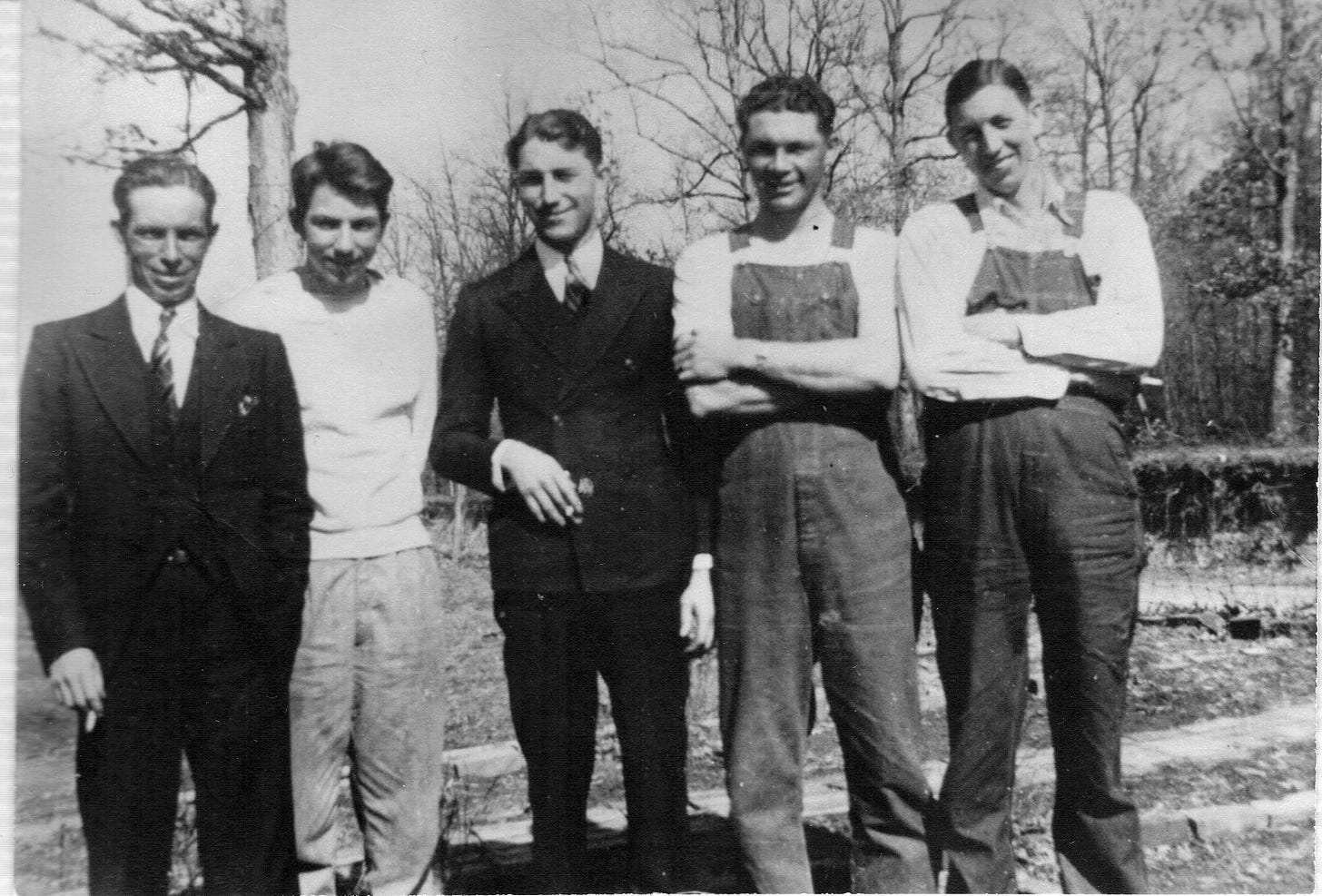

The Bynum brothers, Quentin is on the right.

Incidentally, while his colleagues thought Pine Valley’s nickname came from the area in the Ozarks where he grew up, there is no Pine Valley there. However, there is a resort town called Pine Valley in the mountains around San Diego near where Quentin trained in the horse cavalry in 1941.

Erlyn Jensen, Gold Star sister of William “Don” McCoy, KIA Sept. 27, 1944

“My family was, you just bulled your way through things. But my mom never, never ever was the same. The only time I saw my mom mellow out was years and years later when she was given an anonymous trip to go to St. Avold and see my brother’s grave. And I was married by that time and had two children and our friend who was the travel agent called me and said, ‘Erlyn, I want you to come with me. I’ve got something I need to tell your mom. So I said, ‘Well Newell, you can go down and tell her, I don’t have to go with you.’ And I got the neighbors to take care of the two kids and I rode down with him, and on the way down he told me what he was gonna be doing, and he said ‘You’ve got to support me because I promised this person that I would not divulge their identity.’ And so we walked in the house, Mom knew Newell and she offered him coffee and we’re sitting there, and he said, ‘Ruth, you’ve been given a three-week trip to Europe, the first week in France to go up and spend it at St. Avold, and then two weeks on a tour bus all over Europe.’

“And she said, ‘Who would do that? Who would do that?’ And he said, ‘Ruth, I can’t tell you. It was anonymous, and the only way that it can be given is if you accept that.’ And of course she broke down and started crying and everything, but, she got her trip. And more funny things happened. My sister and I were as excited as she was because she had dreamed about this and we had almost forced her to go into Gold Star Mothers. “No, no, no, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to do that. And she went down and she joined finally a group of women that she really didn’t know any of them but they were all Gold Star mothers and she loved it because they had things in common. And when she got this trip, one of the ladies Mom had never met before before Gold Star, said, ‘Mrs. Moore, I’ll never get to go to St. Avold. If I give you ten dollars will you get some flowers and take them to my son’s grave,’ and Mom said, "‘Oh, I’d be more than happy to do that’ now if you’re gonna cry now wait till I tell you, I mean, if you’ve seen pictures of St. Avold, you know that it’s thousands and thousands, it’s the largest American cemetery in Europe. Mom was taken up there, picked up at the hotel, everything, every step of her trip was planned for her, She was picked up at the hotel in Paris, put on the train, when she got off the train at St. Avold there was someone there to meet her there, walk her in, sign in and everything, and then they put her in a little golf cart, and she said, ‘Erlyn, it was like I went for miles through these fields of white crosses, and she said, ‘Finally, this gentleman pulled over, and he said, “Mrs. Moore, there’s your son’s cross right there,” and gave her a little whistle, and he said, “When you’re ready to leave, you just blow this whistle and I’ll be back”

“And she said she turned around and he just practically disappeared over one of the little hills. And she spent her time, and she knew she could come back the next day, so she spent her time at Bill’s grave. Then when she blew the whistle and he came back she said, ‘Before you take me out,’ she gave him the number of this other fellow’s grave. And he said, “Mrs. Moore, it’s right across the walkway.” And she was able to come home and tell that mother, ‘Your son and my son are right across the sidewalk from each other.’ In those thousands of crosses. So she came home and she was a different woman.

”The Lorraine American Cemetery at St. Avold, France

A death in combat has a ripple effect, like dropping a stone in water, the ripples go in wider and wider circles, growing in size, crossing oceans, until they wash up against brothers and sisters, spouses, children, friends, fathers, and above all, mothers. When Arnold Brown, then a young company commander, was at the head of a column of troops in Normandy, before even his first experience of combat, an artillery round exploded above the column and shell fragments struck a young soldier. “I can hear him today,” Arnold said when I interviewed him in the 1990s, “as he fell he cried ‘Moooommmm.’ That was my first casualty. It still gives me shivers. As Louis Gerrard leaned up against a hedgerow after his tank was knocked out, one eye almost out of its socket, expecting German soldiers to come over the hedgerow at any moment and finish him off, he thought about his mother receiving a telegram that a second of her three sons had been killed (his brother was killed in North Africa).

Tail gunner Sam Mastrogiacomo describes a moment during the Gotha Mission: