Sometimes I wish I could take all the interviews and conversations I recorded and the after action reports for my father’s tank battalion, throw them into a blender, turn it on high for a few seconds, pour it out, and voila! An orderly history of the battalion with names and dates and places would come out, along with 30 grams of protein. Not gonna happen.

The other day I started reading a transcript of a 30-year-old conversation, recorded poolside at the 1994 reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served, and I thought I might have discovered corroboration for something I’d only speculated. My theory didn’t pan out from the conversation, although I found the corroboration in another document while I was trying unsuccessfully to confirm some details from the conversation in the battalion’s after action reports. I’ll explain later, but for now I want to focus on the conversation, with some annotation, because I overlooked Tom Wood in my books about the 712th.

This is the portion of the transcript involving Tom Wood, with some parenthetical of annotations:

Tom Wood, Stan Freeman, Wayne Hissong (and others)

Hospitality room (poolside actually)

Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, Sept. 23, 1994

Tom Wood: I was born in Kansas, and we moved to Indiana when I was about five. We came by covered wagon. My dad and mom and four kids.

Aaron Elson: Including you?

Tom Wood: Yes. I was about five. The youngest, I think, was less than two years old. And then my other brother was born later in Indiana. There were four of us, and all four were in the service in World War II.

Aaron Elson: How many brothers and sisters did you have?

Tom Wood: There were four brothers and a sister. My mother and my sister’s baby were killed in a fire when I was about 19, right after I got out of high school. My sister was 21. The baby died the first night, and then my mother died the next night. The fire was the day before I had to go into the service. So I called them up and told them what happened and they said, “Well, go on out there, and take whatever time you need.”

They were lighting a stove, it exploded, and it got over the baby; she was two years old. And then, after I got out of the Army, my brother and my dad and my brother’s little girl were in an auto accident. It killed my dad and my brother, and the little girl was thrown out on the street. She was back to see us in April. She’s around forty-something now. She lives in Big Bear, California. The baby was buried out in Kansas with my mother and then when Dad got killed, we shipped him back to Kansas, and they’re buried out there.

Aaron Elson: Where in Indiana did you live?

Tom Wood: Down at Dale; that’s about three miles north of Lincoln City. Abe Lincoln’s old stomping grounds. Some of my relatives years ago used to borrow books from Abe Lincoln; the kids used to play together. Nancy Hanks Lincoln was buried in Lincoln Park.

Aaron Elson: When you went into the service, did you go into the 10th Armored Division?

Tom Wood: Yes. Originally that’s where I went. I was going to volunteer and they couldn’t promise me anything, so I said, if they aren’t going to give me anything I’ll just wait to get drafted. The man at the draft board said, “Being as you’re a tractor driver, the 10th Armored Division is opening up; you could probably get right in there,” and I got drafted and got put in the 10th Armored Division. With all the beginners, except the old cavalry; they were there first. All the beginners came in about the same day, within one or two days. And I enjoyed it down there.

Aaron Elson: Were you wounded during the war?

Tom Wood: Well, actually I wasn’t wounded. I froze my feet. At Dillingen*. We went out to fire shells on the town, and my feet had been hurting, and I took my shoes off while I was shooting there because my feet hurt so bad. Then, after we got done, we were going to come back in the trees, and I went to put my shoes on; my feet wouldn’t go in my shoes. Then I had to just slip my overshoes on. From then on, I had sore feet for a long time. Then they sent me clear back to England.

[*The battle for Dillingen, Germany, took place from early to mid-December of 1944.]

Aaron Elson: Did you rejoin the battalion?

Tom Wood: Yes. I started back, and we got over into Germany, and that’s when we saw Germans going west and we were coming east. We knew something had happened, and then they found out at the next stop that the war was over, and that was the reason why the Germans was going the other way, with no guards, no nothing.

Aaron Elson: Who was in your first crew?

Tom Wood: Sergeant Greener, and there was a fellow, he got hurt, well, after Greener got hurt and Richardson got killed, then I had Sam MacFarland and George Rowe and there was a Mexican boy who was the assistant driver and myself. I was the gunner. MacFarland came out of a different tank; then we stayed together until I went to the hospital.

Aaron Elson: Who was your lieutenant?

Tom Wood: Well, at one time, about that time, a fellow, let’s see, I don’t know, because that one guy that got killed up there, or hurt, I don’t know if he got killed but I helped carry him up at the Falaise Gap; I’m not 100 percent sure what his name is, but he was just there and then that happened. Cozzens was in the first platoon there for a while, and then this other guy that came out of the motor pool, he took his place, and I think his name was Miller but I’m not sure. He’s the one that got killed after Bynum’s tank got hit up there. Bynum’s tank got hit and he was in that...*

Aaron Elson: That was Lippincott.

Tom Wood: I don’t believe it was Lippincott, I don’t think that’s his name...

Aaron Elson: Bynum was killed in the Battle of the Bulge. Did you know Bynum?

Tom Wood: Oh, yeah, I knew Bynum.

Aaron Elson: What was he like?

Tom Wood: Real nice fellow. He was a daddy to everybody. I know when us green guys went in the army down at Fort Benning, him and Dess Tibbitts and George Bussell from Indianapolis, they was clowns. They’d get in a pillow fight every night, I think they helped all the young guys, because they were something else. I don’t think there was a guy in there that I didn’t like, in the whole company. When you got into combat, see, you didn’t know what happened to the other platoon because sometimes they’d be down here attached to somebody else, and sometimes you didn’t see anybody else for a week or two.

Aaron Elson: Now, you were a gunner?

Tom Wood: A gunner, uh-huh.

Aaron Elson: Those first couple of weeks [months, actually, but I said weeks], up to the Falaise Gap, what was it like? You must have done a lot of shooting.

Tom Wood: No, not for a while. See, after that, we took off and started toward Paris. And we’d have probably gone into Paris but we got there, and I think the Free French took over Paris. We went around and crossed the river at Fontainebleau. And then after that is when we got in there and got our tank knocked out settin’ in a street. A mortar shell went in the top of it, on top of it, and blew the ring and the hatches clear off of the thing.

Aaron Elson: That was after crossing the river?

Tom Wood: Yeah, I can’t think of the name of the town. [The town was Distroff, France, Nov. 15, almost immediately following the battalion’s first crossing of the Moselle River.]

Aaron Elson: Who was injured then?

Tom Wood: The only one that was injured, and he didn’t have to have medical, was [Sam] MacFarland. When that thing hit up there, it tore that little fan up that...

Aaron Elson: You had said you told him to come down to talk about something?

Tom Wood: I said something to him, he pulled his head down, and that’s when that thing hit the tank. And he told me, “Boy, Tom, if you hadn’t said something to me and if I hadn’t pulled my head down, it’d have been off.” It blew that ring clear across the street, because I had to jump out and go, later, I had to, well, that’s a long story, but...

Aaron Elson: Well, tell me.

Tom Wood: Well, we went in the buildings there and there was a bunch of infantry there, and this woman was in the basement. And they wanted to come up, they was jabbering something. Nobody could understand them but she finally told one she wanted to go down a couple doors and get some stuff out of the house. So, I got my gun loaded to get it ready, and I went out there with her. It was about two doors down, and she went, pecked on the floor, and they raised a door up where a lot of other people were, and she got something out of there, and then we went back.

Aaron Elson: These were civilians?

Tom Wood: Yeah, they were civilians.

Aaron Elson: Was there firing going on?

Tom Wood: Not too much. Because there was a German tank setting down there, and he already had been hit, or infantry or somebody got him. But when Bynum’s tank got knocked out, we saw heads sticking up over a tree, over the hill there, and there was an infantry guy come out of town from our right, and we said, “Who was sticking their heads up over that hill there?”

He said, “If there’s anybody sticking their heads up it’s Germans.” Because, he said, “we’re surrounded.”

Well, when we went over the hill; the Germans was coming out of that field this thick. When we started shooting at them they took off and went back. Then we fought our way into town. When we was settin’ there, one tank went down the street and one went down there, every other one went down the street, and that’s when we was settin’ there on one street just calm as a cucumber and all at once that thing hit the top of the turret.

Aaron Elson: So you had been surrounded?

Tom Wood: No, the infantry had been.

Aaron Elson: So they must have been happy to see you.

Tom Wood: Yeah, they was. Those Germans coming across that field, they was running, you know, attacking, and when we started up there with those tanks we started firing at them and they took off and went back. But that’s where MacFarland said that I got credit, the tank that hit Bynum, on that outer edge there of that hill, and then when it went over the hill there’s a halftrack settin’ there and the German run toward it, and I hit it just as we went in town; we had to zigzag around a tank trap, or a vehicle trap; George Rowe looked there and seen something settin’ right there and he told me to traverse the gun around real fast. He says, “There’s a tank there and he’s about ready to shoot,” and I turned around. It ended up being a halftrack, but when you get starry eyed and in a hurry, and I blowed the back end of it up. But they give me a lot of credit on going in there. But we fired 14 shots at that little old German tank until something flew out in the field. Then we quit.

Aaron Elson: Wait a minute; explain that to me.

Tom Wood: Well, the tank that hit Bynum’s tank, they drove right up beside it. That’s when that officer, I think his name was Miller, he drove right up; we was in the second tank, we saw it, we thought he knew who it was or something...

Aaron Elson: That’s not when Bynum was killed?

Tom Wood: Huh-uh, no, Bynum got killed in the Battle of the Bulge. But they all got out all right, and that officer got back in the third tank, [which had] the two-way radio, and they hit a tree up there with a HE, a high-explosive shell, and shrapnel went down through his helmet.

Aaron Elson: Now explain to me about the 14 shots.

Tom Wood: Oh, well, we shot until seen something fly out away from the tank. Mac hollered, he says, “Well, what are you gonna do?” He says, “The shells are bouncing off of it.”

And when we come out, see, when our tank was hit by the mortar shell down in town there, that evening they sent us back out of town, we had to come right past, and we noticed that one of my shells had hit that tank gun right in the end of it, where they had that flame arrester on it, the thing over the [end of the barrel]. One of my shells had hit him right square, because they was pointing right at us. They fired shots at us but they went over us, and that’s when they got the lieutenant back in the other tank over us. We fired till something had to give.

Aaron Elson: What came out of it, flames?

Tom Wood: Out of the German tank? No, nothing. But that evening, when we come back out with our tank, some guys that had went by there when the Germans started shelling a gasoline truck, all right, he comes out of the gasoline truck and gets over under that German tank, and he said there’s three dead Germans in it. See, that was one of those what they called tank destroyers; it’s a tank on tracks, but you’ve got to move the whole thing to turn your gun; you can’t just move the gun by yourself. Not very much anyway. And one of my shells had hit right near that, so it might have messed him up if he ever tried to fire another.

Quite an experience.

Aaron Elson: Now, what was that [you said earlier] about the baseball glove?

Tom Wood: Oh. When I left England, my brother had given me a brand-new softball glove and a softball, because he was going on a ship, overseas, and he couldn’t play, so he gave me the softball and the glove. I took it, and played when I was overseas, when we had a chance to play. And after I got home, after the war, after 1945, sometime later than that, why, my wife got a letter from one of the officers, if she would keep something, a package, in safekeeping, it was mine. So she filled out the papers and sent it back, and when the box came, the box had been re-wrapped, and it had the ball glove and the ball in there, so somebody surely couldn’t play ball because he’d have kept it.

Aaron Elson: When was your son born?

Tom Wood: He was born the July after I went overseas. And he was born, well, on my brother’s birthday, the day before my birthday, see, mine’s July 25th and his is the 24th of July.

Aaron Elson: And when did you find out he had been born.

Tom Wood: I don’t know, well, whenever my wife got a letter to me, so I don’t know, sometimes it’d come right through real fast, and other times we was in places where we didn’t get mail that regular. And MacFarland’s girl, daughter, was born right at the same time. In fact, when we was up at the Falaise Gap I think his daughter was born about that time, and that’s when he, Mac, lost his glasses up there, broke them underneath an apple tree.

Aaron Elson: What happened?

Tom Wood: The tank driver went underneath the limbs on an apple tree, and knocked his glasses off and they broke, but they was born just about the same time. I wish Harriet [Sam’s wife] had been here, she could tell you exactly. And they named her Lucky.

[That was the end of the conversation with Tom Wood. Later, in the hospitality room, I was speaking with Orlando “Lindy” Brigano.]

Aaron Elson: I was talking to Paul [Wannemacher], he was telling me some things, and I want to get a little more Headquarters Company stuff. He wanted you to tell me about Christmas Eve. The jeep...Not right away, we can get to that. [Spoiler alert: We don’t get to the Christmas Eve incident when three members of Headquarters Company were killed, but I will address that in a later Substack due to the increasing length of this edition!]

Lindy Brigano: We can get to that, yeah.

Aaron Elson: What did you do in headquarters?

Lindy Brigano: I was in the reconnaissance ... and I ran the radio. I was radio for the reconnaissance platoon. I stood there and waited when they went out on a mission, waited for them all to come back. And...

Aaron Elson: The headquarters platoon, was that the three 105 assault guns?

Lindy Brigano: Yeah, they had the assault guns. I was, like I told you, I ran the radio. And they were my boys. I wasn’t gonna go anyplace until they were back from a mission, and when something happened to one of them it affected me because it bothered me in such a way, those are my boys out there, and I used to wait for them to come back.

Aaron Elson: Did you do that from Day One?

Lindy Brigano: From in Europe, yeah. They took me right from Normandy. [Brigano was one of the battalion’s first replacements.]

Aaron Elson: So then were you involved that first day when those headquarters company tanks were...

Lindy Brigano: No, no, no, no. When they landed, I came up, I was a replacement, but I was with them right from the beginning. In fact, I had to walk up the cliff on a big rope in order to get up on top, and once I got there they assigned me to the 712th Tank Battalion, and then they assigned me to the halftrack to run the radio, and that’s what I did.

Aaron Elson: What’s it like in a halftrack?

Lindy Brigano: Well, it’s confining, but not as bad as a tank. At least we could get a little breath of fresh air, and, busy, you know, calling this one and calling that one, and giving information, you know what you ought to be interested in, I think, you know Leroy Moore?

Aaron Elson: Yeah.

Lindy Brigano: Well, he’s got a history of the conversations, things that happened, who said this and what said that, more or less, he compiled it together.

Aaron Elson: Himself?

Lindy Brigano: No, it came down right at the end...

Aaron Elson: So Leroy Moore has ...

Lindy Brigano: Leroy has it, I have a copy too, home. We’re the only two that have it. Now Sergeant Smith had the original, he passed away in California, and there’s only two copies. He has one and I have one.

Aaron Elson: What kind of things would you say on the radio?

Lindy Brigano: Oh, it told who went out on a mission, who came back from a mission, what accomplishment there was on the mission, all that. It’s quite interesting. It’s more or less put into a, how could I say, it tells you “So and so went out today, and he defeated somebody,” you know, when a reconaissance platoon was on reconnaissance, and they were on reconnaissance, they both had a job to do, the Germans and the Americans like us, and sometimes, from a distance, they wouldn’t see one another, but they would go past one another, you understand? And this is what they’ve done here... [For some unknown reason, this is all of this particular part of the conversation I transcribed.]

Later, in the hospitality room

(singing) ... show me the way to go home/I’m tired and I want to go to bed/Oh I had a little drink about an hour ago/And it went right to my head ... Wherever I may roam/On the land or sea/ You can always hear me singing this song/Show me the way to go home...

Roll me over/In the clover/Roll me over lay me down and do it again...

Now this is Number Three/And my hand is on her knee/Roll me over lay me down and do it again...Roll me over in the clover roll me over lay me down and do it again.

(Cliff Merrill) Now this is Number Four and I’ve got her on the floor Roll me over lay me down and do it again/Roll me over in the clover, roll me over lay me down and do it again.

Now this is Number Five and she’s hardly alive/Roll me over lay me down and do it again. Roll me over in the clover roll me over lay me down and do it again.

Jim Cary: What’s Number Six?

Cliff Merrill: We are in a fix. But you can also say, Do you know any new tricks.

Roll Me Over in the Clover (for reference)

------

Stan Freeman: I was an S-3 sergeant...

Aaron Elson: What’s an S-3 do?

Stan Freeman: Operations. My basic responsibility was to see that all of the companies received their rations, gasoline and ammunition.

Aaron Elson: Wait. First, your name is Stan Freeman?

Stan Freeman: Stan Freeman.

Aaron Elson: Your rank was?

Stan Freeman: I was at that time a technical sergeant. I eventually, after they started sending people home I became the battalion sergeant major, but during combat I was a tech. And generally, most generally, at supper time, by radio, I contacted, or field phone if it was possible, contacted the companies, and then they would give me their report on how much ammunition, how much gasoline, how many rations they needed. If I was unable to contact them, then I had to search them out in person. Sometimes this was kind of scary. Not too often, not really, I’m not making myself out a hero or anything, but several times, now, after the, in the wintertime when the Germans took over up in Malmedy, we were down at Fortress Metz. Our battalion headquarters were in a little town called Ste. Marie aux Chenes, and our headquarters was in a building that reportedly was the hotel. It was not in function at that time. And my halftrack had the battalion control radio in it. I can’t tell you what it was, but we could hear anything, we could get all channels. Commercial. Anything, we could get everything on it. And mostly, during any operation, we were on what I call di-da-di-da-dit. I had two operators that ran the channel, and they would send with the key. They did have what they called a bug, which you moved back and forth, move it one way it was a dash, but neither of the operators liked it, they liked the key.

Aaron Elson: And they did it in Morse code?

Stan Freeman: Oh yeah. Morse code. And my one operator, the major operator, the ranking operator I should say, was a fellow named Bray, B-R-A-Y was his last name, and he used to, he was a genius at this di-da-di-da-dit stuff. I remember several times he could send really fast, I forget, I really forget now what the requirement in the Army was, back in my memory there’s a figure 36 words a minute, but I don’t know whether that’s right or not. But he was so damn good, that he would send, and they would block him out, they would hit the key and just block him out because he was sending too fast. We had to slow him down, and chew him out and everything. But if we couldn’t contact them, either by radio or field telephone, one of us would have to go out. Generally I would go with a jeep driver, we’d go out and try to find the unit. This was scary, but really, any of those I would say at the most maybe 10 expeditions that I had to do that, I never came anywhere close to being killed. Or hurt, actually.

Aaron Elson: Did you go out alone in the jeep?

Stan Freeman: Yeah, generally I would go, sometimes I’d take another person and there’d be three of us in the jeep. And generally this was after dark, because we would exhaust every possible method of contacting them prior to that. And if we couldn’t, and we knew that they were in an area where they had been in contact with the enemy, you’ve got to contact them. And actually, sometimes they would send a vehicle back and contact us, send a tank back to find out, because you can’t fight a tank if you haven’t got gasoline and ammunition. It was really something.

A little side thing here that had nothing to do with my job, but we were in this place at Ste. Marie aux Chenes, it’s down in, oh, it was I would say ten to fifteen kilometers from what they called Fortress Metz; it was a circle of fortresses, and at one time five of our tanks got in there and none of them ever came back.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Stan Freeman: Oh yeah. As far as I know. I would get these reports all the time.

Aaron Elson: Do you know what company that was?

Stan Freeman: No I don’t. [This was likely from another battalion.] I did, but that’s too many years ago now. But I remember, from Ste. Marie aux Chenes straight across, there was a level kind of ground, then there’s a slight rise up this, there were wooded areas on both sides and woods in the back of that. And every afternoon, there was a German soldier would come out there, and he was an observer. And when he’d come out in this opening, he stayed squatting, and you could see he had a scope or something in his hand, the shelling would start, and the shells came in on Ste. Marie aux Chenes. And we contacted, in conjunction there was an Army pioneer outfit; this is, well, I don’t know what you would associate it with today...

Aaron Elson: What kind of outfit?

Stan Freeman: They called it a pioneer outfit. And they had a sharpshooter...

Aaron Elson: Was that like the Rangers?

Stan Freeman: I think today that’s what they would be. And so the officer, our commanding officer contacted them. They had a sharpshooter there, and they brought him over. I remember the officer he came with was a, oh, a large guy, very tall, skinny guy, red hair, big red handlebar mustache, and they went up in the steeple of the church on the west side of Ste. Marie aux Chenes, and this guy sandbagged himself, and he had a scope on this, this is an old Springfield bolt-action rifle, they called star gauge. He went up there, and I mosey over, I went up there, I didn’t get clear up the steeple but I was on the ladder where I could look at him. He lay down, sighted in on this guy when he came out. And I saw him shoot. And I raised up and looked at this guy, this guy, actually, this is, the guy was out there taking a crap. He had come out and dropped his pants and squatted down on his knees like that, relieving his bowels. And he shot this O-3 Springfield, and ohh, I’m not good at distances, but it was a thousand yards at least. And this guy stood there like, I thought sure he missed him. And then all of a sudden this German soldier stood up and pitched right forward on his face. He hit him dead center. This guy was a marksman. A little side story on what happened.

And of course across the street there was another place where people lived, and there was a real good chick that lived over there, ask Caffery about her (laughing). Ask him.

Mike Solomon: Aaron, you’re listening to a lot of bullshit again. These guys with all the lies.

Stan Freeman: Well, I lie better than I do anything else (laughing). But I swear to God what I said was true.

Aaron Elson: So you were in Ste. Marie aux Chenes for a while?

Stan Freeman: Ste Marie aux Chenes, how long were we there? I think it was three to four weeks.

Mike Solomon: I wasn’t there.

Stan Freeman: You weren’t in Ste Marie?

Mike Solomon: Hell no. You know where I was?

Stan Freeman: Where were you?

Mike Solomon: In the jailhouses trying to catch up to the outfit.

Stan Freeman: How does a jailhouse move?

Mike Solomon: The MPs couldn’t find the outfit.

Stan Freeman: I’ll tell you, if you want a good story, talk to him.

Aaron Elson: He won’t talk to me.

Stan Freeman: Well, he blames everybody else for lying. Talk to him.

Mike Solomon: I told him, I said, “Aaron, you’ve got enough lies in that book, you don’t want any more from me.” And that’s what he put in the book, he sent it to me. Oh, that was bad. Court martial. Assault and battery with a deadly weapon.

Stan Freeman: With intent to kill? You hit him with a creampuff.

Aaron Elson: Did you see the fight?

Stan Freeman: No, until he told me I didn’t even know...

Mike Solomon: The MPs said, “We want your guns.”

“Over our dead bodies.” This was while we were in jail.

Aaron Elson: Wait a minute, who’s we?

Mike Solomon: Karl Friend and myself.

Aaron Elson: Oh, Karl Friend? He’s dead now. But he used to live in New Jersey.

Mike Solomon: He used to play sax with Gene Krupa’s band.

Aaron Elson: Go on.

Mike Solomon: Yeah.

Stan Freeman: Oh, yeah. You know, there was a couple guys, there was a couple guys when we were in Amberg, you remember, they got up that orchestra? And there was a couple guys there from big-name bands. One of them was from Tommy Dorsey, and I forget, there was another one, it wasn’t as big a name as Tommy Dorsey, but I didn’t know about your friend.

Mike Solomon: We were in the same tank. So now, they lock us up in jail.

Stan Freeman: You deserved it.

Mike Solomon: Karl says, “I’m gonna shoot that sonofabitch.”

“Hey, we’re in jail, how the hell are you gonna shoot him?”

He says, “Right here.” He’s got a little Beretta.

I said, “Put that sonofabitch away.”

He said, “Well, let’s get drunk.”

“How the hell are we gonna get drunk?”

He pulls out a quart of wine.

Stan Freeman: You know what? I think we reduced the alcohol content of France and Germany by quite a lot.

Mike Solomon: I think so.

Stan Freeman: Do you remember, after the war, in Amberg, when they made the beer tank down at the end of the compound? And we went down there, and of course the beer was free, they had gone to a brewery in Amberg and got them to set up and make it, but it was green beer, it was terrible. Oh, my god. And I remember the first glass I got down there was served in a mason jar; you got it in a mason jar. We didn’t have glasses. Oh, Lord.

Mike Solomon: I couldn’t catch up with our outfit.

Stan Freeman: Were you walking or what?

Mike Solomon: No

Aaron Elson: Where did that take place, in France?

Mike Solomon: Yeah. I missed all the war, so I didn’t no nothing.

Aaron Elson: You did catch up eventually?

Mike Solomon: Oh yeah. I caught up. They gave us a court martial, following a brief court martial there was a keg of beer.

Stan Freeman: Do you remember, if you got VD it was an automatic summary court martial? Automatic.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Stan Freeman: Oh yeah. I’m talking Stateside now, but if you got VD, you got an automatic summary court martial. And, what was it, three or six months they took so much of your pay away, with the summary? Was it three or six.

Wayne Hissong: I believe it was three.

Stan Freeman: They took two-thirds of your pay for three months.

Wayne Hissong: What did they call it, when you went on sick call with it, they had a name for it.

Mike Solomon: The best one I ever had, I went to bail out of the tank, right, so I get to this goddamn barracks there, it’s a [Polish] DP camp. Twenty-eight women, that’s all. I didn’t come back to the outfit for a week.

Stan Freeman: You know what? After we got to Amberg, oh, east of us there there was this, oh, I don’t know what they called it, but it was these deposed people...displaced persons, and one day, oh, Lieutenant Seeley, who was battalion adjutant, just after Herring went home and they made me battalion sergeant major, he said “Come take a ride with me.” And we drove over there, and you know, the thing that was, the strangest thing about that, these guys were drinking that bomb fluid, and it killed them; the thing that was funny, you went down the line, they were stretched out on the ground, and none of them had shoes on, these dead people. None of them had shoes. As soon as they died, the other prisoners took their shoes, because shoes were a scarcity.

Aaron Elson: What were they drinking?

Stan Freeman: We called it buzz bomb fluid. It was denatured alcohol, wasn’t it, or something?

Mike Solomon: Fuel of the buzz bombs.

Stan Freeman: Yeah, they fueled the buzz bombs with it. And they were drinking it.

Mike Solomon: What the hell, we drank it.

Stan Freeman: Did I? And didn’t know it?

Mike Solomon: I drank it.

Stan Freeman: Well, then, you’re strong. You’ve got a gut like a ...

Mike Solomon: No, we used to take a slice of bread, snotty old handkerchief, pour the junk in there, bring it through the bread, put orange juice in there and drink it.

Stan Freeman: You know, I thought I was an uncurable alcoholic, I just met my peer.

Mike Solomon: For two days after that, you’d swear you were walking on air. You weren’t touching the ground.

Stan Freeman: But you know, that was the strangest thing, we went over there, this was the battalion adjutant, Lieutenant Seeley, we went over there, just he and I and the jeep driver, we went over there, and they had these, like a perimeter of a tent but they didn’t have any sides, and they were long, I don’t know what they were. But these guys were laid out shoulder to shoulder in there, dead. They were all dead. They had died from this, but all of them either had only stockings on if they had stockings or were barefooted. And, of course we asked, “Where’d their shoes go?” But the other people there had took them because shoes were a real scarce item. You were at Amberg, weren’t you?

Wayne Hissong: I got in Amberg. I was in the hospital when they moved into Amberg. We’d been in there, oh, hell, about a month before I got back to the outfit.

Stan Freeman: Do you remember they started those truck trips, like to Berchtesgaden. And then there was someplace else they went. I wasn’t able to go, but they made trips, this is after ...

Side 2

Aaron Elson: Where did you join up?

Stan Freeman: I was the fourth person drafted out of my draft board in 1941. Until that time they had volunteers, and I found out later that I replaced a fellow from Westinghouse which was the main company in our town who volunteered, and when he got to Fort Hayes they found out he had tuberculosis, so he got back and I replaced him.

Aaron Elson: And how old were you?

Stan Freeman: Let’s see, 1941 less 15, twenty-six, going on twenty-six. And I was in four years, six months, 14 days, almost to the minute.

Wayne Hissong: I got you beat seven days.

Stan Freeman: You know, if you ask these guys, they can tell you almost to the minute how long they were in.

Wayne Hissong: I had it almost figured out one time, man.

Aaron Elson: How do you know right to the minute?

Stan Freeman: I was sworn in and earned, what was it, 70 cents? I think you got 70 cents a day, because you got $21 a month, 30 days, 70 cents a day, the guy that swore us in said “You’ve earned 70 cents,” at 7:10 p.m. And I got out at 6:54 p.m. four years, six months and ten days later.

Aaron Elson: Where were you from?

Stan Freeman: Mansfield, Ohio, 207 miles up the road.

Wayne Hissong: Yeah, when we went in it was $21 a month, and after 30 days you got a raise to $30.

Stan Freeman: No, wait a minute, not after 30 days, after three months, wasn’t it? I still, I was still getting that when I took my basic. The whole time, and that was three months.

Wayne Hissong: Maybe it was three months.

Stan Freeman: Maybe it was six. Anyway, when I went in, you know, they tried to sell you that $10,000 insurance, and I only took $3,000, and that $3,000 life insurance was $3.01 a month. So my paycheck, or my money, you didn’t get a paycheck, you got paid in cash, mine was $21 less $3.01. $18.99 I think it was. And I went into the cavalry in Fort Riley, Kansas, and the first, I believe the first six weeks we were there we were quarantined; the only town close to you was across that river into Junction City, and we just waited till we could go over there, you know, we couldn’t get out of camp, somebody had mumps, somebody had measles, you were quarantined all that time, and the day we went over there we thought maybe we’d better go back. Junction City wasn’t a hell of a lot.

Wayne Hissong: Did you go to Seeley from there?

Stan Freeman: Where?

Stan Freeman: Camp Seeley?

Stan Freeman: Right. I went to Seeley from there.

Wayne Hissong: I did, too. I went to Camp Seeley.

Stan Freeman: We got into Camp Seeley on July the 2nd, Sunday morning, and oh my god, on July the 4th I drew guard. Down at the stables. And what was, remember our colonel’s name?

Wayne Hissong: Rainier?

Stan Freeman: Rainier. Sunday night about 2 o’clock in the morning I was walking around the perimeter of the stables and somebody came up, I heard him coming up behind me, and I turned around and went to present arms, and hollered “Halt! Who goes there?”

And he said, “It’s Colonel Rainier.”

Hell, I didn’t know him. I’d never seen him. I’d been there two days. And I didn’t know what to do. I’d had all this instruction what to do and I didn’t, and I’ll never forget, he looked at me and smiled. It’s 2 o’clock in the morning and every so far around those stables at Camp Seeley there was a pole with a light on it, and we were almost directly under it. He said, “Soldier? How long have you been in the Army?”

I said, “A little over three months, Sir.”

He looked at me and said, “How long have you been here at Camp Seeley?”

I said, “Two days, Sir.”

He said, “Continue your post.” Turned around and walked away. You know, that’s the one thing I found out about in the Army. The guy, with one exception — the one we went overseas with, the battalion commander — the higher the rank, the better they treated you. The higher the rank, the better that officer treated you, did you find that to be true?

Mike Solomon: I don’t know, I never had much rank.

Stan Freeman: They don’t have much rank in jail.

Mike Solomon: At least, I was a T-5, right. They couldn’t break me because I was a tank driver. I kept my rating all the time.

Wayne Hissong: When we moved up to Camp Lockett I was working in personnel headquarters. And Rainier, they put it in that he was in the hospital, but they didn’t say what for. When I made out my report that day I put out NLD, not in the line of duty. Maaan, you talk about somebody getting worked across the coals, when he saw that.

Stan Freeman: You stood at attention and took it, too.

Wayne Hissong: Oh, man. A Major Wilson was the ...

Stan Freeman: Oh, I remember him...

Wayne Hissong: He was the personnel officer, oh, man, I’m telling you.

Stan Freeman: Oh, hey, did you get yellow jaundice?

Wayne Hissong: Yeah.

Stan Freeman: I did, too.

Wayne Hissong: I didn’t have it very bad, but ...

Stan Freeman: They gave us yellow fever shots, and I would say 75 percent of the regiment got yellow jaundice. Oh, my god. Your fingernails turned yellow. Your eyeballs turned yellow. You pissed dark brown.

Wayne Hissong: Goddd, I’m telling you, that was a mess.

Aaron Elson: Didn’t somebody die from that?

Stan Freeman: We had several casualties.

Wayne Hissong: What troops were you in?

Stan Freeman: A.

Wayne Hissong: A Troop.

Aaron Elson: Did the cavalry have a bunch of battle streamers, the old timers, did they ever talk about like the old campaigns?

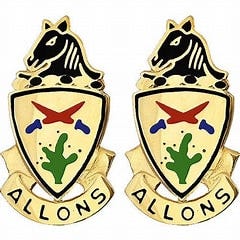

Stan Freeman: Oh yeah, our, the 11th was in, they fought in World War I at Verdun. I don’t know whether they fought as cavalry or whether they fought as foot soldiers, I can’t tell you. At home, in my garage I’ve got a plaque, a picture, really, with their insignia. Oh, I guess it’s about oh, I’d say nine by six, and you have these little “Allons” that you carried on your uniform, and my crossed sabers, I’ve got them, and you know, I can’t find that damn stuff. I squirreled it away and I cannot find it.

Wayne Hissong: I can’t find that Allons.

Stan Freeman: I tell you what, old buddy, if I find my two I’ll send you one.

Wayne Hissong: I remember we went into San Diego, after we went to Lockett up there, and you’d meet the Marines on the sidewalk and they’d salute you. What the hell are you saluting me for? Well, they saw that Allons up there and they thought you were an officer.

Stan Freeman: Hey, you know what? I remember, I got a weekend pass to Long Beach. There were four of us that were buddies in the outfit, two of them were from B Troop and two of us were from A Troop, and three of us got together, one guy couldn’t go, I guess he was on KP or guard. We went out there for the weekend. And on Sunday night, one of the military outfits had a band that played a concert on the pier, right at the beginning of the pier, and the three of us were walking up there, full uniform, this was after D-Day, or after Pearl Harbor, and we were in full uniform, boots, spurs, the whole bit, and they started playing the Star Spangled Banner; the program, they always ended it with that, and so we came to attention, and when you clicked your heels together you made a metallic sound and it was loud. We did that, and I think the 3,000 people turned around and looked at us instead of looking at the band. And we couldn’t understand what was going on. And we went to a, there was a Majestic Ballroom in Long Beach, and this was the first I ever had an experience of running into a major bandleader in person. At that time he wasn’t a major bandleader. We went in this thing and the guy at the gate, it was a nickel a dance, or ten cents, and he gave each of us, there were about five of us, he gave each of us free tickets, just handed them to us. He said “Go on in guys. I’m drafted tomorrow.” And we went in there, and it was the Stan Kenton band. He wasn’t famous then. He was the house band there, at this ballroom, and the thing I remembered about that was he had four trumpets, four trombones and four English horns in his band, and when he let it out, he’d blow you off the dance floor. He would blow you off the dance floor. After that, after the war was over, I paid a hell of a lot of good money to go listen to concerts by Stan Kenton. He was good.

Wayne Hissong: Who was your company commander in A Troop?

Stan Freeman: Miller.

Wayne Hissong: He was a West Pointer, wasn’t he?

Stan Freeman: No, no. Miller was a Jewish boy...

Aaron Elson: This is not Whitside Miller?

Stan Freeman: No, this was a captain. The head of Headquarters Company. I can’t think of his first name now. But he was a captain, he was the head of headquarters all during combat, and Herring was the battalion sergeant major. Jack Roland was intelligence, S-2. I was S-3, operations. Sergeant Burry was the battalion radio, and then we had the two warrant officers, Lemm and I can’t think of the name of the other one. One was motor and the other one was communications, Lemm and, I can’t think of his name. Captain Miller was the commanding officer of Headquarters Company. Whitside Miller was the guy we, what do they call it (laughing), well, we reported him, they reported him to the adjutant general’s office and they sent an inspector out to our camp in England.

Aaron Elson: You said you learned the hard way about officers being good people except him...

Stan Freeman: I’ll tell you, this is a personal opinion, I don’t know whether these guys agree with me, but I always found out that with damn few exceptions, the hardest straight-line officers were always West Point graduates. The best, easiest officers were always reserve officers. I don’t know whether you guys found this out or not.

Mike Solomon: I wouldn’t know because I wouldn’t know one from the other.

Aaron Elson: Was Randolph a reserve officer?

Stan Freeman: I believe Randolph was. This man was like God.

Aaron Elson: Which man?

Stan Freeman: Randolph. [Colonel George B. Randolph, who took command of the battalion on June 6, while the battalion was still in England, and was killed on January 9, 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge.] I’ll tell you, I remember in England we were heading for D-Day and we ended up atop of a hill in southern England, remember, we waterproofed the tanks, and he had just recently, we had scuttled Whitside, and we got Colonel Randolph as the commander of the battalion, and I’ll never forget, we were out in the open — we had a field kitchen — Headquarters Company came down to get in the chow line, and all of the officers were standing there in the chow line first. Colonel Randolph walked by, there was a little bank off to the side, and he said, “Gentlemen, will you join me?” They all went over and sat with him and the enlisted personnel ate first, and then the officers ate. And I’ll tell you, that man earned one thousand points that day. He was a wonderful person.

We had a, on the recon platoon, we had a real, oh, he was a wonderful guy, Lieutenant Marshall [he means Marshall Warfield]. He was head of recon platoon, and when we were down at Metz, he took a group out, there was either a tank hit or one of the vehicles, he took a group out there to try and retrieve it and got killed [According to other accounts, Lieutenant Warfield was killed on a scouting mission]. And that night I was on duty in headquarters; we’d swing around, even, regardless of rank and stayed on duty all night, I was on duty that night and Colonel Randolph was sitting at a table, it was in the hotel at Ste Marie aux Chenes down on the main floor, and they came in and told him that Lieutenant Marshall was dead. And I was setting over, and I watched that man. He put his head down on that table and he cried, real tears. I mean, when he brought his head up he was wiping wet off of both cheeks. He was a wonderful person, he really was.

One other, I’ll give you one other story, then I’m going back and talk to my wife before she divorces me, but I remember, we were in, it was in the wintertime, I’m a little bit hazy now but I think it was when we were transferring from down at Metz up to Malmedy [the battle of the Bulge] and he got killed, Colonel Randolph got killed, and this jeep driver had taken me out to get a report, and it was a little town, and we went in there, and I saw this with my own eyes: There was this tank [it was a tank destroyer], on the corner, and there laying on the ground was Colonel Randolph. About, well, when we got, remember the concentration camp at Flossenburg, when we got there, the Red Cross or whatever it was caught up with us and they gave us, they’d give us magazines, I picked up a Saturday Evening Post and I opened that up and went through it and there was a picture in there, it said “American colonel killed in action.” It was a picture of Colonel Randolph laying at the front corner of that tank. And I had seen the damn thing, it looked just like I was there again. I wrote home to my wife and to my mother, I told them to go get that, if they could, buy that copy of the Saturday Evening Post, and Gerry, my wife, I think she found it and she gave it to my mother. I had kept that all these years; 23 years ago we moved into a new house and I haven’t been able to find the damn thing since. I squirrel stuff away and I can’t find it.

Aaron Elson: It was the Saturday Evening Post?

Stan Freeman: Saturday Evening Post and there was a picture, a full-page picture of Colonel Randolph lying dead beside the left front corner of that tank.

Aaron Elson: How far do you live from Forrest Dixon?

Stan Freeman: Oh no, he’s in Michigan, I’m in Ohio, he’d probably be, oh, I don’t know, it’s 160 miles from us to Detroit, and he lives farther up in Michigan.

Aaron Elson: He’s got a book with a reprint of that photo.

Stan Freeman: Of that photo? That’s the one I saw in the Saturday Evening Post. If I could ever find that thing I’d send it to you, because there’s an article in conjunction with the picture.

Aaron Elson: You’re sure it’s the Saturday Evening Post?

Stan Freeman: I’m almost positive. I can’t remember, Corporal Blessing, he was a T-5, he was a jeep driver, I think he drove, I’m not too sure but he might have drove for Caffery, I don’t know. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen him at a reunion.

I’ll tell you a little story about Caffery. I’m gonna shut up in a minute. I always thought I was a pretty good badminton player. When we got to England, we were there, what was the name of the camp we were at? And I mentioned one day that I liked to play and I was pretty good. Caffery says they’ve got a badminton court over here where the officers are; he said, “Why don’t you come over and play?” He beat me 21-zip, 21-zip, 21-zip. I learned that he had, at that time he had a national ranking in badminton.

Wayne Hissong: He had either a three or a five handicap in golf, too, I found out.

Stan Freeman: I would drop back to drive it, he’d drop it right over the net and I swear to God the feathers on that thing touched every strand of rope on that net. Oh, he was good.

Aaron Elson: What was it about Whitside Miller that was so terrible?

Stan Freeman: He was crazy, absolutely crazy. I was operations sergeant, and in England we had a program one night, night compass reading. They went out by platoons as I recall. He told me to go over to the finish point, and there were guys posted, he said, “When the first guy comes in and tells you that the first unit is coming in, come and wake me up.” So the first unit, which was of course recon, they were out in front, they come in and told me that they were oh, maybe ten or fifteen minutes from the finish line. I went back over to the barracks there and woke Whitside up, and he chewed my ass out for ten minutes for waking him up. And he had told me to do it! He was crazier than hell. Do you remember when they took all the tank companies over in Wales, on the firing range? I was left in headquarters, and there was, oh, a few of the officers there, and the officers’ mess was adjacent to the headquarters, the office area you might say. I was in there, I had a folding mat — I slept there, I didn’t go back to my nissen hut but I slept in there. He got a telephone call from, oh, what were we attached, we were attached to an armored group. I got a telephone call, they wanted to talk to Colonel Miller, so I got up, took off for the officers’ quarters, which is all of maybe twenty yards from the headquarters building. I went in there, there were maybe six or eight of them that were left in camp. I saluted, and I said, “Sir, you are wanted on the telephone.” And I stood there for the next ten minutes getting my ass handed to me for interrupting his supper. And then finally he came to the phone and whoever was on it had hung up. And then I got another chewing out.

He was crazy. The first time I ran into him was in California, and he was, I think he was in machine gun troop. But we had a weekend pass to San Diego, and one of the favorite drinking and meeting spots in San Diego was the, it was a dance hall but it had I think seven entrances, and when you went in any entrance you ran right into a bar. We were in there drinking at this bar, and he walked in and gave us a lecture on drinking. And then he sat down and ordered a drink himself. Whitside Miller, something else.

Aaron Elson: Was he a colonel in the cavalry?

Stan Freeman: He was with us in the cavalry, when I was in California I was in the cavalry.

(some of tape not transcribed)

Stan Freeman: The last six years that I was at Westinghouse, I worked the first shift, production control, and I worked the first shift and I had to be up at 4:30 in the morning. Do you know, after I retired it was about six years before I could break myself of that habit. I’d wake up every morning at 4:30 in the morning, every day.

(some more of tape skipped)

Stan Freeman: Do you remember when they issued campaign hats? You wear ‘em three months and stuff curls up and they get dirty? So everybody in A Troop were buying these Stetsons, and at the time I think they were $14, so I saved up and bought myself a Stetson. About two days later, on the bulletin board it said “There will be no more wearing of campaign hats other than GI issue.” There was my Stetson, and I didn’t dare put it on. The same thing happened down at Benning. I went up to Atlanta and there was a, they didn’t call them Army surplus stores, but I went in there and I bought a shirt with the little tags up on the shoulder, and I no more than got back to camp then they put an order out, you did not wear shirts with the shoulder tags. The story of my life.

Aaron Elson: You came down with the yellow jaundice, too?

Wayne Hissong: Hell, yes, I don’t know of anybody that didn’t. I didn’t have it as bad as some of them did.

Stan Freeman: Well, you know, I had it, and I come back to civilian life, and I went to work. And every three months, the Red Cross took blood. I was one pint short of a gallon, and they wouldn’t take it anymore. And before that, they used my blood as parts. And then all of a sudden, one pint short of a gallon and they wouldn’t take it anymore. So I haven’t been able to give blood since then.

Aaron Elson: Why wouldn’t they take it?

Stan Freeman: I don’t know.

Wayne Hissong: I went to give blood one time, a fellow that I was working with, his daughter was in Indianapolis in the hospital, she needed a blood transfusion, and I said, well, I’ll give blood. Well, when I go in to give blood, the first thing they asked me was whether I had ever had the yellow jaundice. Now whether it was something that she had or not, I don’t know, but they wouldn’t take me and so I never tried it.

Stan Freeman: I’ll tell you how old I am. The place I worked, one of the fellows there was in a fire and got burned quite badly, and he was in the hospital and I have Rh positive, A type R-h positive, and they found out that I had this, and his wife, who worked at the same place, came in and said, “Could you give him blood?”

I said, “Sure.” He was a nice guy. So I went, during working hours I went up to the hospital, gave him a pint of blood, and you know what they gave me? The nurse took me in the room after giving a pint of blood and she gave me a glass of orange juice and a shot of whiskey. I had never heard of that before, she says, “We always do that.” After the war, I went up to the hospital to give blood, and I said, “What do I get for this?” I said, “The last time I was here I got a shot of whiskey.” She said, “You know what you’re gonna get now? A tuna fish sandwich and a cup of coffee.”

Wayne Hissong: Maybe it was a good thing we got yellow jaundice.

Stan Freeman: I have, I’d say, at least ten friends from where I work who went in the Army, all of them but myself ended up in the South Pacific, and I would say 75 percent of those people died from the effects of yellow, or whatever, they took for malaria, malaria-based causes of death. One fellow, who was a medic, I do not remember the island they were on, but they were on the island with the Japanese, and he was a medic, had no weapon, but, he said everybody in the outfit, in the medic outfit, they got some kind of a weapon, somehow, because the Japanese would infiltrate their camps, and he told me about this incident, his buddy, they buddied up, you know, like we did, and he said his buddy woke up one morning and looked up, he had dug a very deep slit trench, here was a short Jap with one of those swords trying to kill him, he had a mark down his chest. And he had a carbine which he had got from some dead soldier or something, and he was afraid to shoot the damn thing before he, he thought he would fall on him and run that damn samurai sword through him.

Now I can’t verify the authenticity of that story, but he told it. One of the guys was in the silent service, and he said there was a period out in the Pacific there, after Pearl Harbor, there was a period where their sub never surfaced for over a month. Never surfaced. Except to come up periscope high, I guess they suck air or something, they never surfaced where they could come out on the deck for over a month. I never thought I had claustrophobia till after the war, up in Lake Erie they had a World War II submarine up there, down on the lake shorefront, and they had an exposition there, and we went up, and I went through that damn thing. I couldn’t live like that. Oh, my god. I don’t know how they survived. Today, in those atomic subs, they have room all over the place, but those damn World War II subs were, by God, you had to suck in your breath to go by a guy in the hallway.

-------

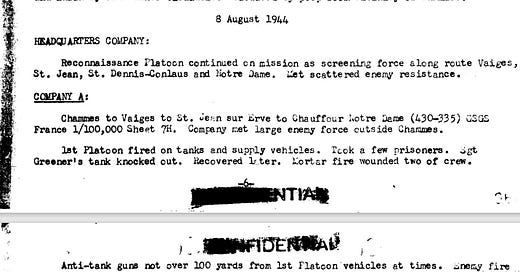

This snippet from the battalion after action report for August 8, 1944, mentions Sergeant Greener’s tank. When Tom Wood mention Bynum’s tank being hit I thought it might corroborate the story I’d heard about Quentin “Pine Valley” Bynum carrying two wounded tankers, one under each arm, to safety, for which he was awarded the Bronze Star. (He was later killed during the Battle of the Bulge.) After reading more of the conversation with Tom Wood, I realized that the incident in which Bynum’s tank was hit was on November 15, and I later was able to find corroboration that he carried two injured men to safety. But more about that in a future Substack.

Just a note: This conversation, which sometimes is all over the place, is just one of dozens of conversations and interviews I recorded at reunions of my father’s tank battalion. I haven’t looked at some of the transcripts in years, but I plan to review and annotate more of them if there is interest. If you’re still reading and found this issue as interesting as I did, you can leave a comment or hit the share button. And if you’d like to support the Substack and help me continue to publish books based on my unique archive, you can purchase one or more of my books from my Amazon author page (my web site is still under re-construction). Also, if you have a Kindle e-book reader, most of my books are available for Kindle.