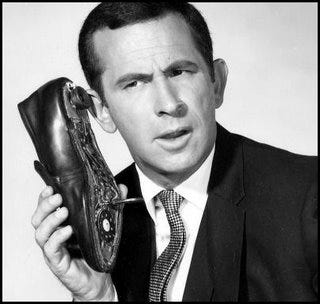

Maxwell Smart: Guess how many Substacks Aaron has posted.

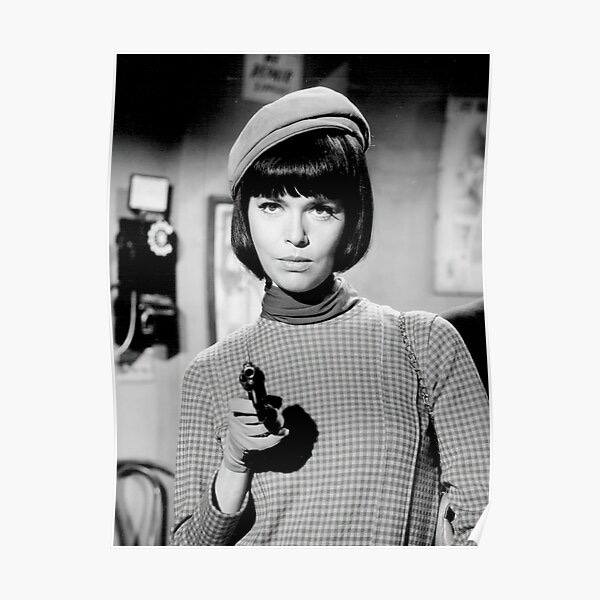

Agent 99: Five hundred?

Maxwell Smart: Would you believe three hundred?

Agent 99: No I wouldn’t.

Maxwell Smart: Would you believe 99?

Agent 99: That sounds personal. Is Number 99 about me?

Maxwell Smart: Would you believe it’s about lunch?

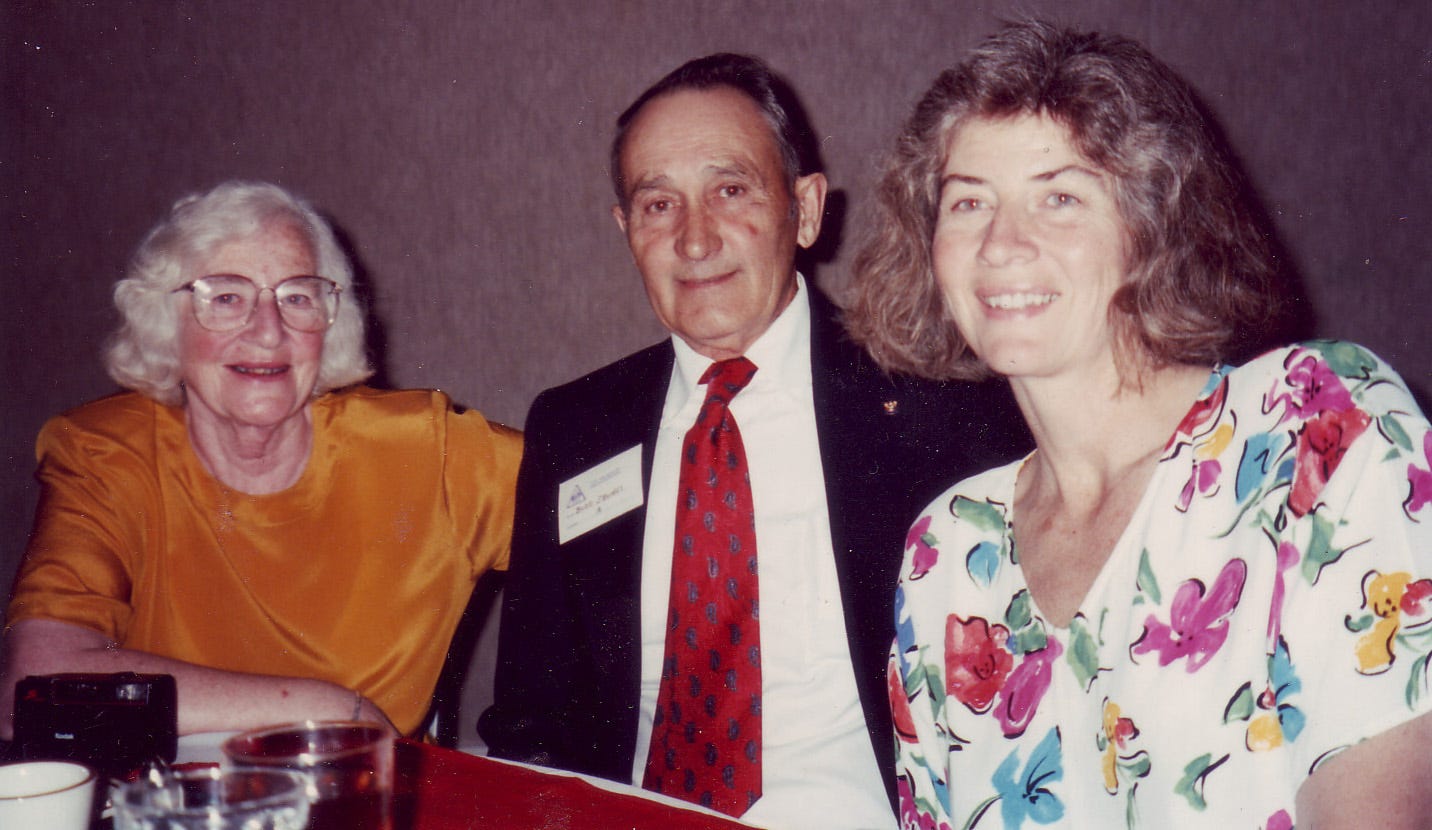

Aaron: Actually, it’s about going out to lunch with four veterans of my father’s tank battalion at one of their reunions.

“I gotta tell you guys a story, you'll enjoy this,” Budd Squires said, blurted really, while I was having lunch with four A Company veterans during the battalion’s 1993 reunion. Squires joined the battalion as a replacement. The other diners: Bill Whitley, who joined after the Falaise Gap in August of 1944; John McDaniel, a tank driver, who also was a replacement; and Neal Vaughn, a gunner who was an original member of the battalion.

“We were in a little town,” Squires said. “I don't remember where the hell it was, just a little shit town we fought to get in, and took the town. We were behind a building with our tanks, and the gas trucks came up and we were gassing up the tanks. But the infantry was still going through the buildings, sorting out stuff. And there was this one infantryman, he went in what was like a basement entrance, the kind you open up and go down into. I was filling my tank. I was holding the gas can, and I watched him go in there. I watched the entrance for quite a while. Pretty soon he came out, and he had his helmet in his hand and he was dragging his rifle like the goddamn war was over. I thought he was hit, so I jumped off the tank and I said, ‘Are you okay? Are you okay?’ He said, ‘You wouldn’t believe it. You’ll never believe it. You would never believe it,’ just like the goddamn war was over. There was shooting going on, and we were behind the building there. I pulled him in and I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘You wouldn’t believe it,’ and he just kept shaking his head. I said, ‘What the hell’s the matter? Are you hurt?’ ‘No.’ But he went down in this building, and he came back out, and there was a couple of nuns down there, and a woman having a baby. Now that was an experience for a guy, and he was just out of it. He didn't give a damn if the war was over or what. That was something. I thought he was hit, but he wasn’t hurt. I remember that clearly. It’s something you don’t forget. I was standing there pouring gas in the tank, from cans.”

The next issue of the battalion newsletter brought the sad news that Budd Squires died shortly after the reunion. It was then that I decided to self-publish the first edition of “Tanks for the Memories.”

“I came into the company at the Falaise Gap,” Bill Whitley, one of the other veterans in the lunch group, said, “and the first major thing that we ran into was the deal at Mairy.”

The “deal at Mairy” occurred on the night of Sept. 7-8, 1944 when the German 106th Panzer Brigade happened upon the 90th Infantry Division artillery command post, with almost the whole 712th Tank Battalion in the area.

“We were together, weren’t we?” said Neal Vaughn.

“We came in at the Falaise Gap,” said John McDaniel, of Paragould, Arkansas, “and they put me in Lieutenant [Harry] Bell’s tank. He was the commander of the third platoon. He was a second lieutenant, and Lester [O'Riley], they brought him over from Service Company and he was our company commander, and he put us down in that little hole. Who was it, it was General [John] Devine, he was commander of the 90th Division artillery, and he had his command post there. So they sent us down to protect that c.p. And when I went back [in the 1970s], it was down in a little wooded area. We got a schoolteacher to show us around. We were in this little wooded area, and then our main companies were up on higher ground. Lester took all the rest of the companies and put them up on higher ground, and we had three tanks right in the corner. The road came around like this, and boy, I mean we were right in front of it. And they woke us up. I never did sleep with my shoes on. For one reason or another I couldn’t sleep with my shoes on, and Bell would get on me all the time. He’d say, ‘We’re gonna get into it. We’re gonna get attacked sometime, and you’re not gonna have your shoes on.’ I said, ‘I'll put ’em right here,’ and I can put the shoes on, I don't have to lace them up. So he got to where he pulled his shoes off.

“When they woke us up that night — really, what happened, one of the kitchen people from this little c.p. fired on these tanks, and when they did, boy, there was just a terrible commotion, and it woke us all up, and I couldn't find my shoes. I reached for ’em where they ought to be and I couldn’t find them. So I got in the tank just like I would have with my shoes unlaced; I just got in it barefooted. I was the assistant driver. Swartzmiller was the driver and I was the assistant.

“We all got in the tank, and Bell, the first thing he did was call ol’ Lester, and Lester said, ‘Are you sure it’s not our people?’ And Bell said, ‘I can read on the tank. They're German.’ And Lester said, ‘You're sure they’re German?’ And Bell said, ‘Yeah.’ So Bell asked him what to do, and Les said, ‘Give ’em hell.' That's exactly what he said.”

“He said, ‘Give ’em all you got,’” Whitley said.

“When he did, old Bell told Swartzmiller, ‘Fire it up,’” McDaniel said, “and boy, when he fired that tank up, now we had an advantage — we had an electrical turret and they had to do theirs by hand. But they were facing right straight toward us so they didn't have much to do. And boy, they fired on us. They hit in our suspension system. That knocked us out. We couldn’t move the tank, and Bell said, ‘Bail out.’ So everybody bailed out. But they put thirteen rounds of armor piercing through the tank, and then set off the ammunition in it. It carried what, 90 to 100 rounds, and then it had a couple hundred gallons of gasoline, and it blew our tank, that ammunition and everything, it was riveted together, right down below where the driver and assistant driver, that front is riveted together, it blew that apart where you could almost crawl in it, that ammunition explosion. I went back the next day. But we all bailed out, and I took off across the field because I knew about where old Lester was.

“Somebody hollered at me and said, ‘Are you American?’ I said ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘Come over here,’ to the wooded area. So I ran over out of the open field into the wooded area, and it was General Devine. And he had his colonel with him. I said, ‘My company commander’s right up here.’ He said, ‘You just stay here with me.’ So he and the colonel were talking. He said, ‘When I woke up, I reached to wake up my driver, and he wouldn’t move. He was dead.’

“Just as soon as it got light I went over there, and that boy was laying there just like he was asleep. He had a little hole right in his forehead; there wasn't no more blood than the end of your little finger. I guess that hot shrapnel pierced his skull and it seared that blood. He looked like he wasn’t 20 years old. That was General Devine’s driver. So I stayed with General Devine, and boy, when you get in combat like that it will really work on your nervous system and your stomach, too. And I had to use the bathroom. He said, ‘Go right back over here,’ and he gave me some digging equipment. So I went over and dug me a place and used it, covered it, and came back. And I stayed with him then till it got light, and when it did, I asked him, ‘You reckon we’re gonna get out of here?’ It was cloudy at the time. He said, ‘Just as soon as these clouds clear out, we’ll get ’em.’ He said don’t worry about it. And he was really cool and calm. I was really surprised. And his colonel seemed to be in good shape, too. So after it got daylight, I started toward the tank and I met old Bell. I said, ‘I couldn’t find my shoes this morning.’ He said, ‘These are not mine I’ve got on.’ I said, ‘They’re mine! I thought they looked like ’em.’ And he pulled them off and gave 'em to me, and then he went barefoot.

“Swartzmiller was wounded, and Bell was wounded too. And [Quinton] Smith, I believe he was wounded too. No, they weren't wounded. We all got out of it. But then when I got wounded, they did too. I got wounded about a week later at a little place called Distroff. It was after we crossed the Moselle, and Fort Koenigsmacher was over there. We were still all intact. What they did then, they fired a bazooka in, and they hit me in the neck and burned my hair off. I don’t know how the others got wounded, but I got back before Bell and Swartzmiller, and I never did know if Smith ever got back or not.”

“When I came off guard that night,” Whitley said, going back to the Sept. 8 battle at Mairy, “it was about 1 or 1:30, and I woke up Arthur Summers; he was another member of our crew. We were on patrol together, and this German column was already there. When they started strafing, these two boys was away from the tank, and old Summers told me after, they was laying as flat as they could, taking their knives, trying to dig a hole in the ground, then they’d lay in it, and roll over on their other side and dig some more. He told me how hard they was working trying to dig a trench.”

“I didn’t tell you right about when I was wounded," McDaniel said. "It was a good while after that. We went to Metz. We stayed there for a long while. After that, we crossed the Moselle, and this happened I think in September, Mairy. I didn’t get wounded until November 16. I was getting my dates mixed up there.

“When O'Riley sent our company down,” McDaniel said, “Bell was in charge of the platoon and I was in his tank, and that’s the reason I could tell you about it. After I left Devine, before I found Bell with my shoes, I was still barefooted. They were throwing those H-E's [high-explosives] against those trees, and boy, it was coming down. I crawled under one of their halftracks, and it happened to be on good solid ground; some of those vehicles, your tracks would mire down and you couldn’t hardly crawl under it. So I crawled under that thing and boy, I thought I was doing good, that shrapnel was falling everywhere, and there was a little jeep right outside of it, and one hit that thing, and when it did, I moved out from under the halftrack. I would still probably have been all right, but that jeep on fire really scared me. I moved out, and that’s when I found old Bell and my shoes.”

As often happened at the reunions, the conversation at the lunch table soon turned to food.

“Do you remember the time we were doing indirect firing over that town of, was it Metz?” Whitley asked. “We were doing indirect firing the whole time. They would go from one end of town to the other, and we would alternate. Just about lunchtime we got hungry, and we were in a farmer’s yard, and I was running down a chicken, do you remember that? And I fell, and a pitchfork was setting with the fork right up this way, and it went right into my finger. Right away a guy says, ‘Go get a Purple Heart. Tell them a shell came in.’ After the end of the war I was sorry I didn’t do that, because I got delayed coming home. I said, ‘I’m not gonna be dishonest about it.’”

“One thing we did,” Neal Vaughn said, “the potatoes, which we used to dig, whenever we had a chance we’d fry up a lot of potatoes. And there were, George Colton was one, several of them ate the potatoes cooked in grease, ate so much of it they got indigestion, I suppose it was, all doubled up. Old Colton, they evacuated him. He never did come back, and I'm sure that’s what it was. I had to start laying off some of that stuff, too. That's the only thing we’d eat.”

“We ate a lot of fried eggs in Germany,” Whitley said. “Our assistant driver, I can’t remember who it was now, went into a barn, ‘Let’s get our eggs.’”

“I forget who was in our crew,” Vaughn said. “We went to a store and we got two cases of eggs, and we divided it up with some of the other crews. I can’t remember who went with me. They were sure good eggs. We'd eat about three or four or five of them each time. It’s a wonder we ever lived through our diet.”

“It's a wonder to me we all didn’t get poisoned,” Whitley said. “They could have poisoned that food for us so easy, you know that?”

“Do you remember when we were indirect firing there at Metz, across the river from Metz,” Vaughn said. “Before we’d go down to indirect fire, and start to move out, they didn’t want to stop, afraid we’d get hit, so we had to move out with pretty good speed. And when you come up to the corner, just before you got to the open fire area, there was a hotel, right in the corner. And one of the drivers didn’t make the curve and hit that big door. And it was a big door. It was big enough that the tank went through it and landed down partway in the next floor. It was one of our battalion tanks, but it wasn’t one of ours. It sure did, it wound up halfway down that hotel basement. He had to get somebody to pull him out. I remember that. I remember some little old town, the infantry boys that went along with the tanks were checking all the buildings and houses. One door was really locked up, a big rock house. I told him to stand aside, we’d open it up for him. I swung the gun around and fired one round. You could have drove a jeep through it.”

“I went back the next day after the battle to examine my tank,” McDaniel said, returning briefly to the events at Mairy, “and one of General Devine's first sergeants, he wasn't a technical but he had a full set of stripes on his arms, boy, he was a big man, he was as big as you are Aaron, and he was lying behind our tank, dead. Evidently he got too close to it and they hit it with H-E probably."

“He was partially burned, too,” McDaniel said, “some of his clothes were.”

“I saw several that were in sleeping bags that never did know what hit them, around that artillery c.p.,” Vaughn said. “The worst of it was they had the sign out there on the road, with a little arrow pointing into our area, so the Germans didn’t have any trouble finding us.”

“Something else you may not know about that,” Whitley said, “this was not really a regular event, like you were marching forward. Really, what happened, is all artillery is behind the lines, and this was 15 or 20 miles behind the line, or 15 or 20 kilometers.”

“What made me mad,” Vaughn said, “was when we crossed the Saar River. We’d just got across the river. Lieutenant [Ed] Forrest was our commander, in the third platoon at the time. We’d just got over and he was drawing on the map what we were going to do the next day. Then he got word on the radio, that’s when the 101st Airborne needed to be helped, and they told us to go up north to the Battle of the Bulge. And we had to go back across, and go about 90 miles in ice and snow, nighttime, and of course the tanks didn’t have lights, the only thing they had was those phosphorous things on the tank. A lot of the tanks skidded off the road, going through the mountains on the ice. And we got up there the next morning, the Battle of the Bulge, ready for action.”

“Early in combat,” Whitley said, “Lieutenant Forrest was wounded, and he came back while I was there.”

“Forrest was the third platoon leader,” Vaughn said. “Something happened and then we had Bell, and then Bell got wounded or killed.”

“He got wounded the same time I did,” McDaniel said. “He’s alive. He’s an insurance guy in Philadelphia. Old Bell, you know, I liked him, because I drove his tank and I slept with him. I was always shaped up and I was clean, and we had to sleep together to keep from freezing in the wintertime, and he told me, ‘You can bunk with me,’ and I did, and I learned to like him. But he was odd as a three dollar bill. He was odd, but he was good to me and I liked him. He made me his driver, after Swartzmiller got wounded, and that kind of irritated one or two of the other drivers. And it didn’t make any difference to me, I’d just as soon have been in one of the back tanks not driving. You know, our tank was knocked out nine times, that front tank was. Nine times. What I started to tell you, I think I was going to tell you about, he got wounded, and we had, in Harrisburg, either Harrisburg or Philadelphia, we had one of the reunions, and he didn’t even come.” [Lieutenant Bell was from Philadelphia.]

“It’s coming back to me now,” McDaniel said a few minutes later. “Swartzmiller was wounded there in Mairy. He was wounded. I was assistant driver. They sent me back to Fontainebleau to pick up a new tank, and I got one of the new, see, the old ones were the old radial airplane engines, and I got a new Ford tank. And Bell told me, ‘You're going to be my driver.’”

This was some luncheon conversation! And it wasn't over yet. You'll notice I hadn't asked any questions up to this point. That was about to change.

“Did you have any encounters with the Hitler Youth?” I asked the group at the table.

“I only remember one evening,” Neal Vaughn said. “Our tank was parked in this area and they did a lot of firing, and they said that’s who it was, the Hitler Youth. I didn’t encounter them. I think they were kind of fanatical, probably.”

“One time there was a bunch of them ran at us,” Budd Squires said. “I don't remember where that was.”

“The Germans were kind of short on manpower,” Vaughn said.

“See, everybody thinks the German army was so goddamn big,” Squires said. “They wouldn’t have been big, but they had divisions of Russians, they had French, they had everybody. Shit, we used to capture ‘em, they'd say ‘Nichts Nazi, Polski. Nichts Nazi, Russki. Nichts Nazi, Franzuschi.’ But the Germans were behind them. They would either get killed, starved to death, or join the German army. They had divisions of Russians, I know that for sure, and Polish, and at the end of the war, where the hell were we at, the Czech border there where we were shipping them back to Poland and Russia, boy, and they didn't want to go. We packed them in boxcars and shipped them back. I think they all got killed when they got back.”

“Poland had a few army units of their own, that trained in England,” Vaughn said. “One day we took some prisoners, and this one young boy, he was in a German tank crew, and he knew these others that were in this Polish unit. They took his German coat off and put on one of theirs and he went with them. I thought that was kind of different.”

“When we went into Czechoslovakia,” Squires said, “we were one of the first units across the Czech border; we ran a task force in there and then came back, but we went into Czechoslovakia, and we hit a town. They had all the white flags up, and they had the Germans tied up to fence posts, wagon wheels, everything. And we got into town and this one guy came over and was talking to [Lieutenant Bob] Hagerty, and then Bob says he didn't understand him, so then the guy started talking German. Bob said, ‘What did he say?’ I said, ‘He's got all these prisoners and he wants to give them to you.’ Bob said, ‘Tell him that we can’t take no prisoners. We ain’t got nowhere to put them. We’ve got to wait till the next outfit gets here.’ This guy says, ‘That's all right. We’ll take them back. But we'll take ’em to the woods.’

“I said to Bob, ‘They're gonna take ’em back.’

“Bob said, ‘That’s fine.’

“I said, ‘No it isn’t. They’re gonna take ’em to the woods. In other words, they’re gonna kill them all.’

“Bob said, ‘They can't do that.’ You know how Hagerty was, he was a real staunch Christian. He didn't go for that shit.

“I don't remember what the hell we did. I think we left somebody there to take care of them. They had them tied to wagon wheels, and these little Czech kids were going by and they were going ‘Heil Hitler,’ and they're tied up to fence posts, wagon wheels and everything. And that's the first ice cream I had all the while I was over there. The Czechs came out with some ice cream for us. Jesus Christ, was that good.

“When the war ended, we were what, 20 miles from Prague, I think, and we had an order to halt and let the Russians come in to us. Well, the Germans didn’t want to give up to the Russians, so they kept coming back to us. And we had a big area, big fields full of German prisoners, and the goddamn Czechs, they’d go up in the woods and snipe at ’em, pick ’em off. Well, they didn't have much love for them.”

“How many tanks did you have knocked out from under you?” I asked my fellow diners. I have no idea how many cups of coffee we were into by now, but there were more to come.

“I lost at least two from German tanks,” Vaughn said. “And one blew up, it hit a charge in the road. And I got hit with an anti-tank gun once. The first sergeant, how many was it, if you got knocked out of four or five he would rotate you. And he told me I could get out if I wanted to, and I said I believe I’ll try it one more time, and the war ended shortly.”

“What was it like in a tank to tank duel?” I asked. Vaughn brought up Mairy, the battle that broke out in the middle of the night which was discussed earlier.

“One we lost there in France,” he said. “I think the 90th Infantry gave a call and they wanted some guard for the artillery c.p. So we took three tanks up there, that’s when we was racing across France. We were up around Nancy and Verdun. And I was on guard that night, I and an infantry boy, and we were walking, and I got off guard and I lay down behind the tank on a bedroll, and I could hear some vehicles moving, and I could tell it was a tracked vehicle, and it had steel treads it sounded like. Well, the heavy artillery has these, they call them prime movers, an M-4, and I thought maybe that's what it was. Then pretty soon I heard somebody say something, and I got up and looked, and what it really was was a whole German armored brigade, and I could see these, we called them halftracks, I don't know, personnel carriers, and they had those three guns mounted on the front. And then there were German tanks. And I woke the tank driver up, he was sleeping next to the road, and then I got the tank commander up. And us three made it back inside the tank. We climbed up over the side opposite where the armored brigade was. And they started strafing just about the time we was getting in.

“That was quite a deal. We did knock off one tank. We had ammunition, armor piercing and high explosive, and then we had a few white phosphorous. Later on we ran out of armor piercing and everything kept on coming. We got out then, we was out of ammunition.

“That was quite a night. A lot of the guys that were sleeping in their sleeping bags with the infantry and the artillery c.p., they never knew what hit ’em, I guess. They strafed that wooded area where we were at.

“That was about 1 or 1:30 in the morning, and it was still going on at daylight.

“I made my way up to where another kid had a .50-caliber machine gun set up and he was by himself, so I stayed with him. And some of the Germans were prowling around out in the woods. It was quite a deal. But I think they lost all of their vehicles, because the whole battalion was stationed in different areas with the tanks.”

“Was that,” I asked, “there’s a little drawing in the history book of the night attack at Mairy?”

“That's it,” Vaughn said. “Our tank was the one that was closest to the road. The tank commander radioed our company and asked what to do, and he said, ‘Well, give ’em all you got.’ At first, we thought maybe they’d bypass us. But they started firing, that’s what started it all.”

“What confusion that must have been,” I said.

“I wasn’t expecting anything, see, and here they came. In the middle of the night, too. That was kind of a scary night to me, anyway.”

“They were all scary nights for me,” Squires said. “The nights were the worst.”

“I didn’t have anything to sleep on, those tanks burned up,” Vaughn said. “So when they were getting hit with the German tanks, you’ve got to get a direct hit to penetrate, and some of them are at an angle. Boy, you’d see the sparks really fly. I went up there the next morning, and you could see where that shell just gouged out a lot of metal. But then some of them hit direct, after we were out of it. They hit us in the transmission a time or two. The tank had been disabled anyway before we got out. One or two went right through the turret, so we’d have got it if we hadn’t got out.”