In 1994, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of D-Day, I interviewed several veterans for the newspaper where I worked. At the end of one interview, paratrooper Ed Boccafogli said the person I should really be interviewing was Pete De Vries. Pete was in Ed’s company in the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment and Ed said he thought Pete was put in for a Medal of Honor but didn’t know if he received it. He also said he didn’t know if Pete would be willing to talk.

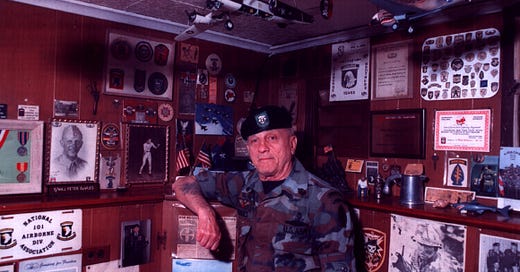

I couldn’t find a phone number, but I had his address in Wallington, New Jersey, so I went and knocked on his door. He invited me in, and showed me his memorabilia room in the basement, but declined to be interviewed. He said the stories you tell should be about the young men who didn’t have the chance to come home. I did get in a question about the Medal of Honor. He said he didn’t get it because he punched a lieutenant.

It took three years, but he finally agreed to the interview, during which he elaborated briefly on the altercation with the lieutenant. It took place after VE Day when a lot of new officers who never saw combat were coming in. An airborne general who knew Pete’s record — it might have been Ridgeway or Gavin — interceded on his behalf and told Pete that if he settled for a Silver Star the potential court-martial would go away. It didn’t help Pete’s cause that he boxed while in the service and was 11 and 2 as a prizefighter after the war.

During the interview, Pete spoke of Medal of Honor recipients he had known while serving with the 82nd Airborne in World War 2, the Rangers in the Korean War, and the 10th Special Forces in Vietnam: Leonard Funk and Chaplain Charles Watters in World War 2, Roy Benevides in Vietnam. Although Pete didn’t receive the Medal of Honor, he was respected by his peers as if he did; in fact, when I interviewed him, the Silver Star had only recently been upgraded to a Distinguished Service Cross.

Although he didn’t think it was right to tell stories, he did tell one, and it was a doozy. He told the story in a letter to the Static Line, a paratroopers’ publication edited by Don Lassen.

“There was an article that some guy from the Marines put in,” Pete said. “He was saying like the different pride the different units had. So he wrote this article, and when I read it, I figured, well, I’ll write this. I didn’t use no names or nothing. I don’t believe in that.”

“Don,” his letter in the May 1978 issue began, “I just read the story by John E. Fitzgerald, but I still think the best one was told by an officer in the tank corps. It seems he came upon this lone GI with a bazooka and told him he was being pursued by German tanks and wanted to know the way to the American lines. After he told the officer the way, he came to attention and said, ‘Don’t worry about a thing, Sir. I’m in the 82nd Airborne and this is as far as those bastards go.’ I think this shows the pride each trooper had for his unit, and what made him the best soldier in the world. Take care, Don. Peter De Vries, 508.”

“When I wrote that,” Pete said, “nobody said anything for a couple of years. Then all of a sudden we went to a dinner in this place called the Drop Zone, and there was this big poster on the wall. It had this guy standing up there with all the equipment, and the caption of, ‘I’m the 82nd Airborne, and this is as far as those bastards go.’ Then they had a couple of guys after that, one guy said it happened in Bastogne, and he said he was sitting a jeep, and a couple of tanks came by, and they wanted to know the way to the American lines, and he says he told them. But like I say, who cares?”

I asked if Pete confronted the fellow who claimed to have made the saying, which would become one of the iconic posters of World War 2.

To which Pete said that he asked the fellow if he knew who the officer was that was trying to reach the American lines.

“How the heck could he be expected to know that?” I asked.

“I’ll give you a hint,” Pete said. “He had a famous father, and he was a Senator himself.”

“I give up,” I said.

Pete said it was Will Rogers Jr., who resigned his seat as a Congressman to serve in World War 2, and was an officer in the 7th Armored Division.

Fact checking fool that I was even back then, I contacted the Will Rogers Museum. The librarian sent me a few pages from the book “Gare la Bete,” by Calvin Boykin, a history of the 7th Armored Division. The excerpts contained an account of a reconnaissance platoon led by Lieutenant Will Rogers Jr. which came upon a sentry and asked the way to the American lines. Rogers then urged the sentry to come with him as the platoon had lost all its vehicles and was being pursued by a pair of German tanks.

Pete showed me the following citation:

Private Peter De Vries distinguished himself on 19 December, 1944, while assigned to the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Werbomont, Belgium. Though wounded and with disregard for his own life, he attacked two enemy tanks that were advancing on his company’s position, destroying one and disabling the other. This action prevented the enemy from breaking through these positions and saved the lives of many soldiers and civilians. His bravery against such odds was in keeping with the highest tradition of the United States Army and the 82nd Airborne Division.

I see now that there is a four-day discrepancy between Dec. 19 and the date on the poster, Dec. 23. I asked Pete if that was the citation for which he was put in for the Medal of Honor.

“No,” Pete said.

Before we get to the other citation, a little more confusion.

An article in War History Online titled 10 of the Coolest Things Ever Said in War, references the book “All American, All the Way,” by historian Phil Nordyke and tells the story of the poster this way:

The picture above is one of the most famous images in the long, proud history of the 82nd Airborne Division. Here is the story behind it: It was December 23rd, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge.

As a tank destroyer from the 7th Armored Division moved west from Salmchateau on the highway toward Fraiture, the commander spotted a lone trooper from the 325th digging a fox hole for an outpost near the road. The commander stopped the vehicle and asked him if this was the frontline.

The trooper, PFC Vernon Haught, with Company F, 325th GIR [Glider Infantry Regiment], looked up and said, “are you looking for a safe place?”

The tank destroyer commander answered, “Yeah.”Haught then said, “Well, buddy, just pull your vehicle behind me. I’m the 82nd Airborne Division, and this is as far as the bastards are going.”

As it turns out, either Nordyke got it wrong, or War History Online quoted his work wrong. Vernon Haught was the paratrooper in the picture, but according to his page at Find-a-Grave:

December 23, 1944 - An entire US Armored Division was retreating from the Germans in the Ardennes forest when a sergeant in a tank destroyer from the 7th Armored Division spotted an American soldier digging a foxhole. The GI, Private Martin, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, looked up and asked, "Are you looking for a safe place"? "Yeah", answered the tanker. "Well, buddy," he drawled, just pull your vehicle behind me.... I'm the 82nd Airborne, and this is as far as the bastards are going.'

Two more versions of the story appear on the web site of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment

The poster is a photograph of a dirty, scrappy, tough paratrooper, PFC Vernon Haught, of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, marching in the dead of that cold, snowy winter with a rucksack on his back. Going to reinforce the retreating American forces in Belgium. His expression leaves no doubt about his determination. He is moving out to go toe-to-toe with the enemy in Belgium. As you look at the poster, it strikes you that nowhere in this photograph do you see a parachute. And you and I both know there doesn't have to be one -- you simply know from the look: he's Airborne.

Under the photo is a quote from PFC Martin, also of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, who during the battle asked a retreating tank destroyer commander, "Are you looking for a safe place?" When the tank commander answered yes, PFC Martin replied, "Well buddy just pull that vehicle behind me -- I am the 82d Airborne and this is as far as the bastards are going." Imagine, an Airborne PFC telling a guy in a tank to follow him."

--General Henry H. Shelton

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Remarks at the 60th Anniversary of the Airborne

Fort Benning, Georgia, April 13, 2000One more version:

Late on the night of December 23rd, Sergeant John Banister of the 14th Cavalry Group found himself meandering through the village of Provedroux, southwest of Vielsalm. He'd been separated from his unit during the wild retreat of the first days and joined up with Task Force Jones, defending the southern side of the Fortified Goose Egg. Now they were in retreat again. The Germans were closing in on the village from three sides. American vehicles were pulling out, and Banister was once again separated from his new unit, with no ride out.

A tank destroyer rolled by; somebody waved him aboard and Banister eagerly climbed on. They roared out of the burning town. Somebody told Banister that he was riding with Lieutenant Bill Rogers. "Who's he?" Banister wanted to know. "Will Rogers' son," came the answer. It was a hell of a way to meet a celebrity.

An hour later they reached the main highway running west from Vielsalm. There they found a lone soldier digging a foxhole. Armed with bazooka and rifle, unshaven and filthy, he went about his business with a stoic nonchalance. They pulled up to him and stopped. He didn't seem to care about the refugees. "If yer lookin for a safe place," he said, "just pull that vehicle behind me. I'm the 82nd Airborne. This is as far as the bastards are going."The men on the tank destroyer hesitated. After the constant retreats of the last week, they didn't have much fight left in them. But the paratrooper's determination was infectious. "You heard the man," declared Rogers. "Let's set up for business!" Twenty minutes later, two truckloads of GIs joined their little roadblock. All through the night, men trickled in, and their defenses grew stronger.

Around that single paratrooper was formed the nucleus of a major strongpoint.

-- from: Anecdotes from the Battle of the Bulge

I have a theory. Although Pete was noncommittal, I believe the iconic statement was his. If he dispatched Will Rogers Jr.’s patrol to the safety of the American lines and remained at his post on December 19, 1944, it is possible — granted, I’m speculating here — that Rogers said there was a crazy paratrooper who said “this is as far as the bastards go” and waited to confront the approaching tanks. Having heard this, Private Martin, four days later, seized the opportunity to use the line in a similar situation. Then somebody thought it would be a good idea to match it up with the photo of Haught.

Later, Pete showed me his other citation from World War 2. It was for a Silver Star, and had only recently been upgraded to a Distinguished Service Cross.

Sergeant Peter S. De Vries, 508 P.I.R., 82nd Airborne Division, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy at Nijmegen, Holland, on 17 September 1944. Though wounded upon landing, Sergeant De Vries advanced forward and singlehandedly wiped out two machine gun emplacements, killing approximately six German soldiers. Sergeant De Vries then led his men in clearing snipers from several houses. At one point he attacked a building singlehandedly, killing two Germans manning a machine gun, while another group cleared a building across the street. After the company had advanced further into the city, at least two German machine guns began firing into the column, pinning down the entire company. Sergeant De Vries maneuvered his point from the line of enemy fire to establish a base to cover the German positions, and without other assistance assaulted one position with a submachine gun and grenades, destroying the position. He succeeded in diverting fire of the enemy upon himself and permitted his company to neutralize the position. The outstanding bravery of Sergeant De Vries and his willingness to close with the enemy contributed in large measure to the success of his company’s attack and rendered a distinguished service in the accomplishment of his company and battalion’s mission were in keeping with the highest tradition of the military service and reflect the utmost credit upon himself, the 82nd Airborne Division and the United States Army.” Robert L. Meisenheimer, chief records reconstruction branch.

In addition to the Distinguished Service Cross, Pete was awarded two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, and a pair of Purple Hearts, among many other decorations. But for many years, all he wore at ceremonies was his jump wings and the combat infantry badge.

“That’s all I ever wore,” he said. “but then one time I was on the Rutherford VFW, and I knew Eddie Smith from the Ranger battalions in World War II, and he happened to be the commander down there. He asked me about joining the color guard. I was unsure from the beginning, but then I says, ahh, what the hell. Matter of fact, I was the only man ever to get on the color guard that was not a member of the post. With that color guard that was an honor, because they had a very outstanding color guard. And Eddie told the guys this and that. As a matter of fact, Bill DePugh, he took over like head of the color guard unit, so they had a dinner, and at the dinner they were announcing the guys from the color guard. When he called for me, I stood up, and then he mentioned my name and everything, and he says, “When the United States ran out of medals to give him he was decorated by three foreign countries.”

So everybody looked around and all they saw was a pair of wings and a combat infantry badge. So they says how come you don’t have any ribbons or anything?

I said, “I just don’t wear them.”

So they all got together, they said, from now on you’re gonna be wearing them. So after that, I started wearing them.”

Between the time I met Pete in 1994 and when I interviewed him in 1997, I thought if he agrees to be interviewed, I’m going to put it in a book. I included the interview in my third book, “A Mile in Their Shoes,” and put his picture on the cover. It’s available at Amazon and for Kindle, or if you’d like a signed copy (by me), you can order it directly from me for $10 plus $3.95 shipping. Contact me at aelson.chichipress@att.net for instructions.

Often when he spoke at veterans ceremonies, Pete would read the following poem.

(Pete De Vries passed away in 2016 at the age of 89)

What a story!! So enjoyed reading it Aaron! Thank you for keeping the WWII stories alive!

Your posts should be compiled as a book . Priceless stuff, all of it. Along with your interviews, they are valuable historical records!