That’s pilot Paul Swofford in the back of the picture, watching as the officers on his crew celebrate a mission being scrubbed because of bad weather. He’s not whooping it up like the others because getting the mission in would have brought him one flight closer to completing his missions and going home. Flyng in a substitute plane named The Sweetest Rose — he grew up in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, not in Texas — his was one of only four out of 35 bombers that returned to the 445th Bomb Group’s base at Tibenham, England. When I interviewed him in 1999 he was still bitter because flying in a damaged aircraft with a wounded man on board, he was waved off because he was about to land on a taxiway instead of a runway, and he was sure he could not gain enough elevation to circle around and come in again.

That interview took place at Paul’s home in Lakeland, Florida, where I noticed a shrine of sorts in a hallway. The shrine was a doll of the famous ventriloquist’s dummy Mortimer Snerd with a baseball cap and a baseball glove with a baseball in it. Paul explained that it was in memory of his son, whose favorite character was Mortimer Snerd and loved to play baseball, and who died at the age of 19. At the time, I didn’t press him for further details.

Paul and his wife, Sybil, were Southern Baptists, and often asked me if I had found Jesus yet. Perhaps because they lost their only son, combined with the fact that after that interview he was able for the first time to express his anger about the taxiway incident, getting it off his chest as it were, and reconnected with the Kassel Mission Memorial Association, Paul and I kept in touch and I would try to visit him whenever I would go to Sarasota for the annual “mini” reunion of my father’s tank battalion.

When I visited, Sybil Swofford would always press me to get Paul to tell me about how he was so poor during the Great Depression that he took a cow with him to college, and about how, despite the poverty, he developed a love for flying. So on one visit I took my tape recorder and we sat down to talk.

My 1999 interview with Paul Swofford

Aaron Elson: I want you to tell me a little bit about the Depression, about growing up in the Depression.

Paul Swofford: Well, I was living on a farm, and we had a big family. I was in the third grade at school when it started in 1929, but we didn't know anything about, or I didn't know anything about what was going on. Here I am, about eight years old. But we noticed it in our, well, in what we were able to go to the store and buy. I was aware that my folks didn't have any money coming in and we didn't have biscuits for breakfast anymore. We didn't have any biscuits to take to lunch to school. Since we lived on a farm we raised corn, so we had cornbread three times a day. That was one of the things that we noticed, but being a young person like that, I wasn't aware of what all my folks went through.

Aaron Elson: How many brothers and sisters did you have?

Paul Swofford: My mother and father had 16 children. One of them was born in 1914, and it was a boy and he died after three weeks. But there were 15 that lived, that after they were grown had children and so forth. Two of us, or one of them, one family didn't have any children, but all the rest of us had children, that were our parents' grandchildren. So one of 15 is the way I grew up. And I had older brothers in school. Most of the girls came along after my time, but mostly boys to start with, only one girl and about seven boys. I was the eighth one. So we had living eight boys and one girl at the time, and then the girls finally overtook us because there were so many girls after, some of them after I left home.

Aaron Elson: Where was the farm?

Paul Swofford: It was in western North Carolina, in McDowell County. That's where I was born, in McDowell County, near Marion, and we later went to school at, or we moved, near Mitchell County. That's where Spruce Pine was the largest town, and so we children went to school at Spruce Pine and that's where I got my high school diploma in 1937. And if you start counting, you'll see that if I started in 1927 and graduated in 1937, there's only ten years there, so when we changed school, I conveniently skipped a grade. So all through high school I was the youngest one in school. And when I started college I was the youngest one in my freshman class at college.

Aaron Elson: And how did you go to college?

Paul Swofford: Apalachin State Teachers College was close to us at Boone, about 50 miles away, and I had two brothers that were also going to school there. Incidentally, in spite of the Depression and the fact that we didn't have any money at home and so many children, before me there were three of them that got bachelor's degrees and a college education. So it was just natural when I finished high school that I would also go to college, and that's where I met my wife, Sybil. Sybil says it's the greatest thing ever happened to me was that when I came up to my senior year, I dropped out. The reason I dropped out is, I didn't have any dollars to go to school, and I realized that my senior year I would have to do practice teaching. That means a couple of suits of clothes. I didn't have a suit of clothes, and I didn't even have enough money to register. So I dropped out for a year, went out West at 19, 20 years old and worked for a year and came back in ’41 before Pearl Harbor and started back in and about the first day of school Sybil and I met each other. First day of school. I was a senior and she was a freshman just coming in, and Sybil says the greatest thing ever happened to me was that I didn't have any money, I had to drop out of school, because I'd never have met her. And that made a lot of sense.

Aaron Elson: When you went out West, what kind of work did you do?

Paul Swofford: I ended up working down in California on a ranch that raised sugar beets and aspara ... well, they had asparagus but mostly it was sugar beets, and my job was to work on a rain machine. Now, rain machines, they didn't have much, any rains in the summertime out in central California around Sacramento, so we had to lay these water lines, get water out of the canals and pump them with a tractor to put some pressure and they called them rain machines, the whirling two streams of water. So we let that soak for an hour or so, and then shut her down, and move it over about fifty feet and set up shop again. That's what I did for, oh, I guess about six months out there in the summertime.

Aaron Elson: And you were able to save up enough money to ...

Paul Swofford: Yep. I held onto everything and came back, and that's the first time I'd ever lived in a dormitory. In my previous years I had to work for my room and board and scratch around. It only cost me $25 to register at school. Twenty-five dollars. I never did have any textbooks, couldn't afford 'em. I'd go to the library and read their copies, but I'd have to turn 'em back in at the end of the hour when I'd go there. But I didn't have any problem remembering in those days, like you do when you get a few years on you, you know, sometimes you don't remember what you went to the bathroom for!

So that's the first time I'd ever lived in a dormitory with other people. I had a roommate who was about four years older than me, but we were both seniors that year. I did practice teaching. That was a wonderful experience, at that age. Here I was 20 years old, and I was doing practice teaching. And I was doing practice teaching at the time of Pearl Harbor, in December of '41. So I graduated in the spring, got a bachelor's degree, and then I went right — my father and mother, I had told them all along that I wanted to be a pilot. That's before we were in the war. And my dad would say, "Well," he says, "I'm not gonna sign it for you," because I was underage. The requirement was to be 21 and have at least two years of college in those days. That was in 1941. But my dad would say, he says, "I'm not gonna sign it." His sly way of telling a joke I guess was never to laugh about it, but he would say, "I wouldn't mind flying an airplane at all, so long as I could keep one foot on the ground." That was his kind of humor. But when I did graduate that year, after Pearl Harbor, they lowered the Selective Service age. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Selective Service was only inducting people who were at least 21 years of age. That's the ones that signed up for the draft. But just after Pearl Harbor, a month or two later, they lowered the age to 20.

So I was 20. I had to go sign up, and from then, from February to my graduation I was really on pins and needles because I was afraid I was gonna get drafted before I could get a chance to finish college. I knew that the day I was 21 I headed to Charlotte and signed up for the aviation cadets. Of course such things as mathematics and so forth on it, here I'm just a brand new college graduate, it was no problem to pass the written exam, and the physical exam, so I passed, and well, the rest is history. I did become a pilot for the next 24 years.

Aaron Elson: What was it that Sybil was telling me last time I was here that you and your brother took a cow with you across a mountain?

Paul Swofford: Well, we did. Since I skipped a grade, it put me up just one class behind my brother who originally was two classes ahead of me in school. I've always thought there was a little bit of resentment there; of course he isn't alive anymore so I can say that, maybe a little bit of resentment his kid brother is nipping at his heels. But he had married when he was a sophomore in college, at 18 he got married. Married a lady who was a senior in college, and so he took a cow that was his, at home, a neighbor had a truck, and hauled that cow up to Boone, and he found a place to feed the cow and stake it out to graze the grass. So that was my junior year, say '39 and '40. We had a room in a place that had a bathroom outside and had a shower outside, and he'd milk the cow and sell about half of the milk. He sold half of the milk for ten cents a quart, and and we drank the rest of it. He did most of the business with the cow, all the milking and all the selling and all of that. I was just a young squirt to him.

Aaron Elson: Are there still a lot of Swoffords in that area, in Spruce Pine?

Paul Swofford: No. There's some, I have a cousin, a first cousin, my dad's brother's son, that we always went to school with. We're dearest friends. He's 93 right now, just had a birthday recently, 93, he's not in too good health. He's got a sister who's 91, but in my family, we went to the four winds, you might say, because of World War II. Or, I guess you'd have to go on back and say the Depression, because I had two brothers to drop out of school before they graduated from high school, and they went out to, quote, "seek their fortune," and as it was, I don't know why they did it, but they left home when they had finished about the eighth or ninth grade in school. One of those now is the 93-year-old, but of those who, well, there's three boys that we have left in the family, with the Swofford name, but, you know, Sybil and I, we lost our son when he was 19 in 1963. He had just completed his sophomore year at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. On June the 6th, we were just saying yesterday I was putting up a new calendar for the month of June, I said "On Saturday is the fateful day." It was just 19 years after D-Day that he lost his life. He'd just finished his second year at the University of North Carolina and was home for the summer, and I was on temporary duty, we call it TDY, out to California, to Merced, checking out in the, what we call the KC-135 tanker airplane.

Incidentally, later when I came back I was the commander of the KC-135 squadron, I was the commander of the field maintenance portion of the KC-135 wing. That airplane was originally the DC-9 that the airlines used. Douglas built that DC-9.

Aaron Elson: So you were overseas when your son was born?

Paul Swofford: No. I went overseas in '44. It took about a year to go through flight training, and then nearly another year to train on the B-24 to go to combat, so it took about two years there to get ready to go to combat, so I went over; I left at the end of June of 1944, it's just in the same month as D-Day was the 6th of June '44. So we were given an airplane. From our training camp we went to Topeka to pick up an airplane. They gave us a brand-new airplane, and I had a crew of ten, and we flew it across the northern route, up through eastern Canada and Greenland and Iceland and so forth, to the British Isles, and we became part of the 8th Air Force.

Aaron Elson: What year was your son born?

Paul Swofford: Our son was born in '43, probably a year after we were married. He had his first birthday when I was, well, it was just about the time of the Kassel Mission. His first birthday. There was only a couple of us on the crew who were married. It wasn't always easy for the other members to understand what being married meant, you know, how the two of us who were married and had children, we knew how to communicate with each other, you might say, easier than it was with the other fellows.

Aaron Elson: Who was the other crew member who was married?

Paul Swofford: That's Waller, Joe Waller. He was my ball turret man, but we got to England and the first thing they said, "Give us this airplane, we're going to send it somewhere and take the ball turret off of it." Well, when we got to our combat group, they said, "You've got to eliminate one of your men.” So we discussed it with my co-pilot and my crew chief, because those are the ones I'd always consult on matters like that. "What do we do?" And it was unanimous among us three that eliminate one of the others and keep Joe Waller and put him in another position, because we didn't want to lose him.

Aaron Elson: What position did he become?

Paul Swofford: Tail turret gunner. He was the first one to see the enemy on my aircraft on the Kassel Mission because they were coming in from the rear. He had one definite kill and one probable, and my engineer manned the upper turret all the time; normally the engineer would be standing between the two pilots, and we'd talk about the functioning of the airplane, the functioning of the engines and so forth, so we had to have him there to talk to us. But when we would get into enemy territory, he would man the upper turret, and he had a probable. So we had one kill and two probables assigned to my crew.

Aaron Elson: You had said that Steve's first birthday was around the time of the Kassel Mission?

Paul Swofford: Yes. Steve was born on 10 October of '43. And that was in late September of '44, the Kassel Mission, so he was just short of his first birthday there.

Aaron Elson: And it was June 6th that the accident was?

Paul Swofford: That's right. June 6th of 1963, he's just about four months, a little more than four months short of his 20th birthday. He came home for the summer and, as I say, I was in California, and, he had come home for the summer, and another young fellow there that he palled around with. We lived on the base, in base housing, and I had gone off, I was assigned out to California to that KC-135 school and Sybil was there alone, and she went down to Chapel Hill and picked him up and brought him back home. And the two boys, our son and the other boy, the other boy had his father's car. So they were out on the afternoon there, just before they were both gonna have a job for the summer. And the boy, the driver, decided to pass another car, and it happened to be right on a rise. I don't know why, it would have been surprising because it was almost in front of the high school that both of them had attended. They were familiar with that road. But he decided to pass on the rise, and went head-on into another car.

The other car was driven by an airman's, a sergeant's wife from Lockbourne Air Force Base where we were, in Columbus, Ohio, and the other, the sergeant's wife was killed also in the accident. Head-on. And the driver, young driver, about the same age as our son, had a broken arm. That's, that was the of, that's the end of our descendants, right then and there.

Well, it just so happened that particular day, the 6th of June, had long been my graduation day from my KC-135 schooling in California. That was at Merced; it was Castle Air Force Base, and we graduated in the morning. Of course, being three hours earlier out there, by the time I started home, about noon I started driving East. I had my own automobile out there. So that was about 3 o'clock Eastern time and about noon our time out there that I started driving. And towards evening, it was approaching darkness, somewhere around Needles, just before I was to get into, I don't remember if I would come into Nevada or Arizona, both of them are pretty close there, but as I was approaching Needles, I decided, as it got dark, that I would find a motel. So I saw one and I just drove right into it, in the driveway, near the office, and I looked in my rearview mirror, and right on my rear bumper was a highway patrol ... highway patrolman. And I got out of my car and I said, "Well officer, is there a problem?"

He asked me if I was Major Swofford. I was a major at the time. And he said, "Call your command post." I'd never heard of such a thing, but apparently the authorities back at Lockbourne in Columbus had called. They had first contacted the military at Merced and they said I'd already left, heading East. And so, I don't know where they got information about the car, but that policeman, the highway patrolman, had been alerted to, I think all of the patrol were alerted to look for me. And they said, “Call your command post.” So before I even checked in at the motel I went over to find a place to call, and there was only one pay phone in all of that little, it was just a village then, Needles; that's quite a while ago, and there was one pay phone that was available. And there's a long line there, so I had to get in line, and I got in, and it was always arranged when we were away from the base that I could just put in a quarter and call, and the number that I would call they would return the quarter to me. So I got the base number, and called and talked to my commander, and the commander told me that my son had been killed that very day. And so, so then, I had the, well, I had the commander to give me back the command post there. It was hard for me to talk — like it is now, really — after 46 years, it's hard. But he gave me the command post there that was on the base, and I asked them where I was. And they told me, they said, "You're just a hundred ..." I was a hundred miles south of Nellis Air Base, which is in Las Vegas. And so I asked him, while I was on the phone there, I said, "How about you making arrangements for me?" I said, "I can drive up there, but I don't know, you find ..." I said, "I have no way of knowing what airplanes are flying" and so forth. So the people at the command post got ahold of the airline office out in Las Vegas, and he found out that there was a plane heading East about two hours from then. And they said, "We told them, if you didn't get there, to hold it."

Well, that was a pretty hard drive, you know. At night, a hundred miles, and I had to go across Boulder Dam, Lake Mead and Boulder Dam, strange territory, at night, by myself, not even knowing where I was. But I finally got to that airfield in Las Vegas, it was a hundred miles away, and they were holding the airplane for me.

And when I had talked to the commander earlier, he told me they couldn't, that our son had lost his life about 4 o'clock in the afternoon, and they couldn't find Sybil. Sybil had gone up to town and was spending the night in town somewhere, and they hadn't found her yet. So I heard the news before she did.

Well, before, when the commander told me that, there were people outside the phone booth back there in Needles, they wanted the telephone. They were clamoring there for me to shut up and get out. And since they couldn't find Sybil there's no point in me calling her. So I called Sybil's mother. Steve was the first grandson, he was the light of their life. And I started off by saying, "I'm out in the middle of the Mojave Desert, in Needles, California," and she says, "Well, how, how wonderful. How are you getting along?"

And I said, "I didn't call for that." I said, "Steve is dead."

And, I know that shocked Sybil's family from head to toe. But I got up there and got on that airplane, left my car there, parked there in the lot, and headed East, and the next morning I was at home in Columbus. And Sybil met me at the door as I came in. That's a tough time.

Aaron Elson: What sort of a kid was he? Was he like a, an Air Force brat?

Paul Swofford: Well, we always lived on an Air Force ...

Aaron Elson: When I say Air Force brat, that's not meant to ...

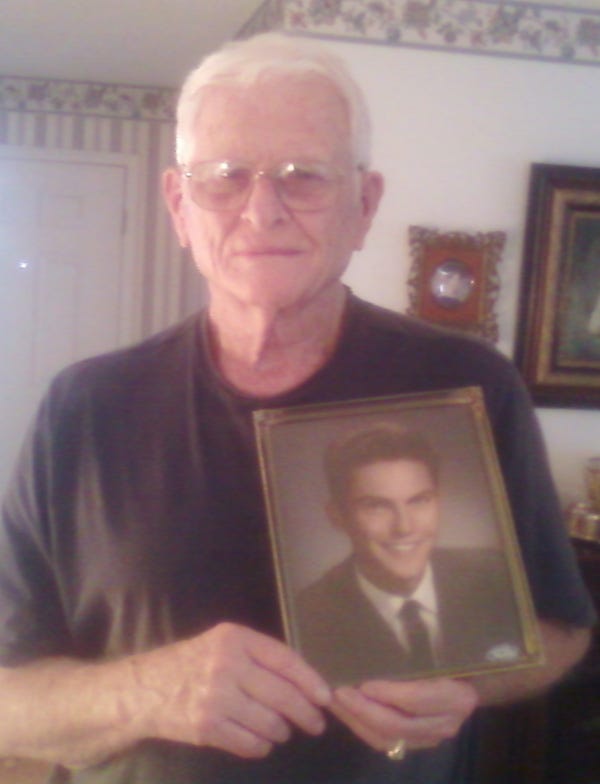

Paul Swofford: Well, I know what you mean. He didn't much like the idea of me being in the military. It didn't send him any at all. But he was a, a wonderful, wonderful young fellow. Just look over your shoulder.

Aaron Elson: Oh my goodness, a good looking kid.

Paul Swofford: That was made when he was 19. That just, I've missed him every day. And so has Sybil, but she's not as vocal about it I guess, as I am. I'm the one in our household that brings his name up all the time.

Well, after that, I'd already had three tours overseas, one tour in England in combat, later had a tour in, just at the end of the war, '46 to '48 in Okinawa, for about a year and a half, and left them at home. And then in the mid-Fifties I was sent up to Thule in Northern Greenland for a year and left them at home. And it came up to 1965 and I was approaching 24 years in the military; that's when I was the commander of my field maintenance squadron at the time. I was still on flying duty, and so I took a Goony Bird, that's a C-47, took it to Holsom Strategic Air Command personnel; we were part of the Strategic Air Command or SAC as we called it, had to take some of their personnel to some of the outlying sites down in Oregon like stopping at Portland, and so forth, and I learned by looking at my manifest that they were from the personnel section at headquarters, Strategic Air Command at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha. So I turned the controls over to the co-pilot there, and I said, "I'm going back and talk to this chief of personnel back there," and I said to him, when I saw him, I said, "I've been stationed at Lockbourne Air Force Base there in Columbus for eight years, I'm eligible for retirement." I said, "I've got 23 years," and I said, "Do you have anything open down in Florida where I can spend my last years in the military?"

He said, "You mean you've been stationed here for eight years? Why you're red hot to go to Vietnam."

Of course, the Vietnam business had just started a little bit before. And when I came back from the flight, came home, I said to Sybil what had happened there. She said, "What time does the personnel office open tomorrow morning?" I didn't have to ask any questions. I knew what she meant. And I did it. I was there when they opened up the next morning, I said, "I want to put in for retirement." So I put in for retirement there, and I asked the personnel chief, "How safe is this now? If something happens after I sign this, can it be called off?"

He said, "Negative. If you put in for retirement and we accept it, you'll retire." Well, that same personnel office, about ten days later, called me at my office and said, "I've got a TWIX for you." That was a military message. And he said, "You need to come over to the personnel office and read it."

When I got over there and opened it up, it said, "You have been reassigned to Ton Son Nhut Air Base in Vietnam, in Saigon, and to report immediately to be the chief of maintenance there." And I just laughed like I laugh right now. I said, "Well, Colonel," I was a lieutenant colonel at the time also, I said, "That's hilarious, isn't it?" I said, "I'm safe, right?"

He said, "You're safe." Because Sybil had said, "I don't want you ever to leave me again." She said I've been away too much, we lost our son, and said, "If you went over there, in the first place you may not come back, and the other is, we're gonna be apart." So I retired in about six months then in January of 1966, got credit for 24 years' service. Pay wise that means 60 percent of base pay for retirement.