Korea, Vietnam, Mrs. Bradley's dog, and William Tell

Part 2 of my interview with Colonel Clifford Merrill

Clifford Merrill, who was the original A Company commander in the 712th Tank Battalion during World War 2, went on to serve in the Korean and Vietnam wars. This is the second of two parts of my 1992 interview with Colonel Merrill. For Part 1, click here.

Cliff Merrill: The first man killed was Lieutenant Tarr, and he’d say “so and so had joined Tarr’s platoon.”

Aaron Elson: Why was it that the censors wouldn’t allow that...

Cliff Merrill: That was just the policy. They didn’t want discussion about casualties or places you were going. Initially we tried to figure out a way, from Point A, “we’re 200 miles north of Point A,” but they wouldn’t accept that either. They figured out what Point A was after a while. And there was no way of getting by with that, so we didn’t try it anymore. They’d cut it out and tell us not to do it. But in each unit, of course, you had to censor your own. The lieutenants, for example, had the job of censorship of their own men. And in my case I had to review some of that stuff, but hell, I wasn’t able to check up on all that, I was busy. I was out on the line all the time. I’d leave that to Ellsworth Howard [the executive officer], to worry about that stuff. But Charlie Vinson was one hell of a good first sergeant, and he took care of a lot of things like that. A real good man.

Cliff Merrill: Mrs. Bradley [General Omar Bradley’s wife] was rather an eccentric type. When I took the job, went in as the provost marshal in Fort Myers, Virginia, one of the first tidbits of information was that Mrs. Bradley was to be handled with kid gloves. Be careful how you do it. Well, one day she called the office and said, the provost sergeant answered the phone, and he handed me the phone quick; he said, “It’s Mrs. Bradley.”

She said, “Major. There’s a great big dog jumping on my little dog.”

I thought for a moment. I said, “Is that little dog a female?”

“Yes. But she’s been spayed.”

And I said, gee, this is a tough one. I said, “Yeah, Mrs. Bradley. No doubt the dog’s been spayed, but you know that big dog doesn’t know that.”

She cackled, and said, “You’re pretty smart.”

I said, “I’ll come right over and handle it personally.”

When I went over the dog was gone, of course. But she invited me in to have a Coke. I got along well with her.

Aaron Elson: And then when she was speeding around the...

Cliff Merrill: Oh yeah, she drove pretty fast, had a kind of a car looked like an old, what the hell make of a car was that, it wasn’t a Reo, it looked like an old Essex. I don’t know what make of car it was, and anyway, she made the turn around the post exchange building around on the straight, and the car leaned over; it went on two wheels. The MPs were behind her. She was really moving out fast. She called me and said the MPs were harassing, were chasing her.

I said, “No.” I said, “They reported it to me and told me about it. They thought there was something wrong with your car, and they didn’t know but they might have to render assistance.”

“Ohhh.” No more said. So, that took care of that one.

We had, even among kids, rank was considered. I caught three of those little kids one day, one was a chaplain’s son, another one was General Parks’ son, and another general’s, no, a full colonel’s son. They had somebody’s hunting bow, and hunting arrows, and they were trying to play William Tell.

The chaplain’s son was junior, of course, he had to hold the target. And the others were trying to shoot the bow and arrow.

I put a stop to that. In fact, in the course of doing it, of course one of those arrows hit them across the ass. That didn’t go over good with Mrs. Parks.

Aaron Elson: It hit the chaplain’s son?

Cliff Merrill: I hit ‘em all. I spanked “chtttt” “Now get the hell out of here now. Don’t ever do this again.”

General Parks didn’t know about it at the time but Mrs. Parks, she called me. She read me up and down. “This is Mrs. Parks.”

I said, “How are you today, Ma’am?”

“Don’t Ma’am me! That’s my son you struck.”

“Oh,” I said. “That wasn’t anything. It was just a reminder to him that he shouldn’t be playing with dangerous things like bows and arrows that are steel-tipped.” That toned her down a little but not enough to suit me. I didn’t say anything further, but she told General Parks.

General Parks called me. He said, “I understand you had occasion to strike my son with an arrow.”

I said, “I certainly did, Sir.”

He said, “How did it happen?”

I told him.

He said, “Good. I’m gonna whip his ass in good shape.”

But I didn’t give a damn then. Understand, at Fort Myers, Virginia, [there were] 23 generals. And that meant there were 23 general officers’ wives. That was the problem. Keeping everybody happy.

Aaron Elson: As the provost marshal, what were your duties?

Cliff Merrill: Oh, just the chief of police. Discipline, law and order were the general terms. Anything goes wrong, call the provost marshal. I got calls all the time of the day and night. I’d say “Call the office. The MPs are well-organized, they know how to handle these things.” As long as it wasn’t Mrs. Bradley.

Aaron Elson: Your position at the time, you were what?

Cliff Merrill: I was provost marshal at Fort Myers, Virginia. This was in 1950.

Cliff Merrill: I went to Korea in ‘52. From Fort Myers I went to officers career course, and then I went to Korea.

Aaron Elson: About how old were you at that time? That’s 42 years ago?

Cliff Merrill: In 1950 I was 36. I was born in ‘14. What did you want to talk about, Korea?

Aaron Elson: Just briefly. What was it like, in Korea?

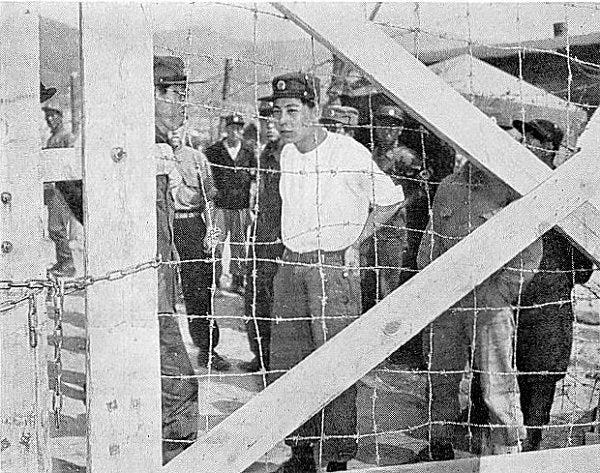

Cliff Merrill: The part I got in on was handling the Pws. In Koje-do and then on the mainland, too. On the mainland I had non-communists, anti-communists. They were friendly. But not Koje-do, they were very unfriendly. It was quite obvious in Korea that the prisoners were pretty well organized. They had an organized resistance, and they had a plan to discredit us because our own, we were our own worst enemy, really. Everybody got shook over what the newspapers were gonna say. Nobody had the guts to kick the damn reporters out of the way. Really. I didn’t like them. Same situation in Vietnam. Anyway, to put down a riot, there were no guidelines as to what was a reasonable amount of force, well, what is a reasonable amount of force when you’re faced with ten to twenty thousand screaming meemies trying to crash a fence? What should you do? Let them run over you? You have to; if you’ve got a machine gun you have to use it. And if you don’t, what we didn’t realize maybe is you could shoot one in the face, that discouraged them. If you shoot them in the torso, it didn’t bother them that much. But the disfigurement factor would stop them quicker than anything else.

Aaron Elson: Is that a cultural thing?

Cliff Merrill: I don’t know what it was. But anyway that would cause them to discredit their, change them from looking like a conquering hero, you might say, to a common thug; I think that was part of their philosophy. There was one battalion commander, a North Korean, Lee Hak Ku was his name. And he surrendered. He surrendered his men. But I think, I really believe that was a planned thing to come into the PW camps and there they’d organize riots and so forth. They were successful for a while until we finally identified the leaders, Lee Hak Ku among them. Isolated them. Put them in solitary, and so forth. Then things quieted down a bit. Their leadership was gone. But on the transfer, what they called the Big Switch operation, we had to watch; they’d try to riot and upset our schedule. We were moving up trainloads of them and moving back our people who were turned over. We didn’t get as many, of course. Theirs went up in the thousands, and the returnees from our side were only in the hundreds, by comparison. I think that was their plan, to disrupt things. They ruined everything they could. They cut up the seats, broke the windows in the railroad cars. We’d transport them from the train station at, I have to think a minute for the name of that siding where we transferred, it wasn’t Mun-so-nee, Mun-so-nee was our base camp. Ke San was a base camp for the Koreans. They met at Panmunjon but prior to that, I think we called that, I believe it’s Freedom Station I think, I’m not sure. But it’s across the Nektong River, the north side of the Nektong. I think it’s Freedom Station I believe they called it. There we transferred them to trucks. In the meantime, we’d given them new uniforms, new combat boots. Everything brand new. Toilet articles. Really stupid. But you can’t criticize your seniors. But anyway, on the way to near Panmunjom they dismounted from the trucks but prior to getting there, they’d cut all the canvas off the trucks, ruin everything they could, and each time somebody’d give us an order to put new canvas on. We had a major general in charge, and I asked him, I said, “What’s the sense of putting canvas? These damn idiots don’t appreciate it, and they’re gonna cut them up.”

“Well, that’s what we have to do.”

So I thought that was rather stupid. After a while they saw it was going to be pretty expensive, and they’d take a whole trainload of people, I forget now how many, but three or four thousand, on trucks. And the way we transported them was seats on the side, two and a half ton trucks with a bench in the middle, straddled, they’d straddle that bench. And I forget now, but I think it was forty or more they put on each truck. If they carried GIs it was only 18 to 20 people, but with them we could double it. And the way you do that, you get all you could get in, the driver would start the truck, and slam the brakes. At that time you could throw in another half-dozen. You learn things.

Aaron Elson: Your position then was what?

Cliff Merrill: At that point I was the operations officer at the Big Switch operation.

Aaron Elson: And what was your rank at the time?

Cliff Merrill: Major. I was still a major, in fact, I made lieutenant colonel in ‘54.

Aaron Elson: And what were you when you retired?

Cliff Merrill: A full colonel.

Aaron Elson: How did you wind up in Vietnam after that?

Cliff Merrill: I was with the 1st Infantry Division. I was a provost marshal, and we were at Fort Riley, Kansas. Orders came down; of course we knew where we were going. We went from Fort Riley by bus to Topeka, Kansas, where we boarded planes that flew us to the West Coast. And then on the West Coast we transferred to bigger planes. The plane I was in had most of the division staff, and two jeeps on board the plane. It was a big four-engine, big thing. And we flew to Okinawa, and then, it was Guam, Okinawa, and then into Vietnam, landed at Pusan, at, there was the Air Force base there, what was the name? I forget.

Aaron Elson: Was this towards the beginning or the end of the war?

Cliff Merrill: The beginning. We were the first combat troops of the Army to get in there. I think the Marines had landed up near, they’d gone in up in the northern part, in the midsection, near Hue, in that general area.

Aaron Elson: So this was what, about 1968?

Cliff Merrill: Oh no, this was ‘65 I believe. ‘65 or ‘66. ‘65, because I came back in ‘66. I didn’t last too long. Seven or eight months.

Aaron Elson: And your position there was?

Cliff Merrill: I was provost marshal initially for the 1st Infantry Division. Then the commanding general moved to corps and took me with him, and I became the corps provost marshal, which was a bigger job but I actually didn’t do as much as I did before.

Aaron Elson: And how did you come into a combat situation; were you in combat when you were wounded?

Cliff Merrill: Combat was everywhere. There were no rigid front lines. You could become a casualty in the middle of any town. I had highway security, amongst other jobs. I had men who were out on the road all the time, subjected to all kinds of things; land mines were a common occurrence. Daily occurrence really, and we lost troops that way. The way I got hit was, we were in a convoy; I was leading the convoy. I always went out in advance. We had to go over the highway to see what it looked like, and you could sense; you’d go over these highways, dirt roads is all they were, and we’d find, I was testing to see if I could draw fire or what; it didn’t make any difference, because we were moving right along. We were well-armed. I had machine guns, and a 75-millimeter recoilless rifle, it takes a shell about two feet long. We had, this was an 1,800-head convoy.

Aaron Elson: 1,800 vehicles?

Cliff Merrill: Yeah. We were going up to the Michelin plantation. They had troops going in. We were initial support stuff, supplies; you couldn’t fly everything in. They had built an airstrip in the Michelin plantation, but some planes couldn’t get in there. And some of the heavy stuff had to be hauled overland, and that’s what we were doing. In the convoy was troops, tanker trucks, food, ammunition trucks. And there were three explosions behind my jeep. And I thought they were mortar shells. But they weren’t. They were land mines. We were moving right along.

So I knew the jeep had got hit. I didn’t realize I had. See, I didn’t wear a vest. I sat on it. To protect the family jewels. And we stopped, and I told my driver, I said, “That guy was shooting at us,” those mines. “Those were not mortar shells.” So I gave a halt to the convoy, and I was looking around on the hillside. It wasn’t steep, it was just rising ground, really. And I told the driver to get on the machine gun and I’ll go look. But I didn’t have, I had hand grenades and a little snubnose .38, that’s all the weapons I figured I’d get by with. So we went, I went up this hillside. Through my glasses I could see this change in the contour of the terrain, a little hump. And I went up there, and hell, there was this well-concealed cover for a hole in the ground. I kicked that cover off, and this old guy gave me the Buddhist salute and when he did I shot him through the top of the head. But he had aiming stakes, three sets of them, he set off three mines. And he was the one. He was too old, his reflexes were not too good, that’s why he didn’t get us. He was an old guy. That’s the way they did it, they’d have a stake here, a stake here, in his case he had three. You’d line these things up, eyeball, then when somethings along, you touch your wires, move over to the next one, touch your wires, and so forth. Simple. Crude. But very effective.

See, my people were some of the first ones in the division to get killed, and I didn’t have any, it didn’t bother me to kill him. If there had been more of them I’d have been happier to kill them all. I got rid of him.

Aaron Elson: Understandably. At that time you were hit already?

Cliff Merrill: Yeah, in the upper spine. Little tiny pieces. Nothing showed. Like a faint scratch. I didn’t feel anything much. Oh, about two or three weeks afterward, my left arm started getting numb. I thought it was a heart attack, you hear all kinds of things. I knew, I didn’t figure I was a candidate for a heart attack, I was always rugged and healthy and all. So I went to the medics and they X-rayed me, and said “We can’t help you here, but you’re going, get your things together, you’re going back tomorrow.”

That’s how I was evacuated. Back to Walter Reed. And they didn’t operate on me either. They said, let’s wait and see what happens. It got a little better, the numbness was not as pronounced, but I ended up having to be operated on, a very extensive type operation. I lost the use of the arm, the arm isn’t good yet. It never did come back all the way. And that’s how I ended my war career.

Aaron Elson: You were no kid then. You must have been in your forties?

Cliff Merrill: Oh yeah, I was 55 when I retired. I retired in ‘69. But I was batted around, I tried to come back on duty, and went to Fort Dix. I was down there about six, seven months. I couldn’t cut it. And they kicked me out. Unfit for service.

Cliff Merrill: There was something, I thought of it last night, I didn’t write it down. Oh yeah, from, after I got out of Walter Reed I was, the First Army commander was General Seaman. He’d gone from the 1st Division in Korea, field force commander, and went to Fort Mead, Maryland, he was the commanding general of the First Army, and he called me one day, asked me what I was going to do. I told him I guess I was going to retire. He said, “I would like you to go down to Fort Dix for me.” They’ve been having problems. The provost marshal there was not successful in keeping prisoners in line. They had a lot of prisoners, I guess over 1,500. The system was, in Europe, all the bad actors, they’d ship, transferred there. They’d hold them a while pending trial or pending their being put out to places like Leavenworth, long-term, murderers and stuff like that. Real bad actors.

Aaron Elson: Were these American soldiers?

Cliff Merrill: Yeah. And they were kicking up; he didn’t know how to handle it, so he asked me if I’d go out and take it. I felt pretty good, but I wasn’t exactly a hundred percent good. So they tested me, and found I could handle them all right, and they quit. I had an MP battalion there ... But I would, I went in with a group of men. I told them how to do it. We used, we didn’t use pickaxe handles, we used sledgehammer handles. A handle like that, they’re hickory, they don’t break. You catch them in the face, it discourages them. What led up to this was the fact that these were old wooden barracks, two story types, and the people inside were, in each barracks I had unarmed people to maintain order. If they needed something, they could call, and we’d help them out. They dropped a footlocker on one of my kids. That caused me to take action. We went in. They tried all kinds of things. They tried to set a fire, and barricade the doors, but we were determined so we went in, and operated on them a little bit. Knocked out some teeth and broke collarbones. A couple of them I guess they busted an arm or so. But used a reasonable, I termed it a reasonable amount of force. No gunfire or anything like that. We didn’t have any guns. We did have those sledgehammer handles. They were very effective, if you know how to use them. But we toned them down. Then this shoulder and arm got pretty bad, I probably did something wrong. I’d already been operated on, this was in ‘68. So they sent me to the hospital, and I was in the hospital four or five months, taking treatment, and they boarded me out.