Several Substacks ago I wrote about the search through my archives to see if I could identify a tanker crossing the Werra River to come to the badly needed aid of subscriber Ron Ammons’ father’s infantry company. As it turned out, I was able to identify Lieutenant Francis “Snuffy” Fuller as the tanker who volunteered to risk fording the river, although it turned out that the picture itself was of a different tank in a different river.

Fuller, in his late twenties, from Tonawanda, New York, was placed in command of the second platoon of Company C in the 712th Tank Battalion after the platoon’s lieutenant, Leo Hellman, suffered combat fatigue in August of 1944.

Fuller “was sort of a quiet fellow,” Ralph Tambaro, a driver in the platoon, said at the battalion’s Orlando reunion in 1993.

“A real quiet little fellow,” Otha Martin, a tank commander in the platoon, said. “We had a man ahead of him, but he wouldn’t fight.”

“He broke down under fire,” Rego said.

“They transferred him to the quartermaster,” Martin said. “They’re way back. They don’t even hear artillery. Now Snuffy, he’d fight.”

“And he could play the piano for you guys, too,” Rego said.

And so begins this Substack about loot.

“I picked up a V.C. Hohner Tango accordion, 120 bass, over there,” Rego said, “and we were in Amberg,” where the battalion was stationed following the cessation of hostilities in Europe. “I had it already boxed up, and he [Lieutenant Fuller] told me that I couldn’t take it with me as company material, that I’d have to ship it. But then I’d have to have somebody sign that I had purchased it. And Snuffy told me I’d never get it out of there, why don’t I give it to him? He wanted it in the worst way.

“I told him before I give it to him I’d put my goddamn foot through it.”

Undeterred, Rego came up with a plan to get his accordion home. It began with some coffee grounds. He worked in post utilities, and had a good rapport with the German workers there.

“These people in post utilities were just ordinary scared Germans,” he said, “and every meal that we had, breakfast, dinner and supper, we always had coffee, and they probably had somewhere in the category of three 20-gallon aluminum containers.

“They’d put about 20 pounds of coffee in a bag and stick it down there and just punch the devil out of it with a stick.

“Some of that coffee was not completely expelled, and they used to take it out and throw it away. And some of the German fellows realized it still had a reasonable amount of strength, so they dried it out, and when they were going out the gate, one of the guards stopped them and threw them in jail. I talked to their supervisor about it, and told him if he ever wanted any of the used coffee, let me know and I’d take care of it.

“I worked in the fire department, and we used to all eat early chow. When I ate, I’d go wash my mess kit out, then I’d go over and fill it up again and take it over to the fire hall. There were two German fellows over there who worked in post utilities, one was Eric and I can’t remember the other fellow’s name, but they took turns eating.

“One day they were standing around and Eric had a cigarette in his mouth because he had picked up the butts he found. But he had nothing to light it with. I said, ‘Do you want a cigarette lighter?’ So I gave him a cigarette lighter. I must have had a dozen of them.

“But no fire,” he said.

“So I said, ‘Don’t worry about that.’ I got a Coke bottle and I got him some hundred octane gasoline, filled it up, and it burned wonderful.

“So they took me in as a half-decent guy. I could walk in there and get anything in post utilities. So I said to the supervisor, ‘I need a favor.’

“He took the pencil off his ear and said, ‘What do you want?’

“I said, ‘I need a bill of sale that I bought this accordion. If I don’t get a bill of sale, they won’t let me take it to America, and I’m gonna have to put my foot through it.’

“He said, ‘No problem.’ So he went over to the typewriter and said, ‘This man is dead, but nobody knows it but you and I. But I verified the transaction between you and Mr. So and So for 1,000 marks.’ That would be a hundred dollars in American money, ten cents on a mark. So he gave me that piece of paper, and I went over and I said to Snuffy, ‘Read that, god damn you. Now how are you gonna stop me?’”

Rego was home for about four months before the accordion caught up to him, but he finally got it home. “My oldest girl was taking the piano and the accordion,” he said, “but it was too doggone heavy for her to lug around, so I thought maybe I could take it up. But I was working maybe fourteen, fifteen hours a day, so I didn’t have time. So I had a friend, he was divorced, and he had a tough time, but he lived on a 147-acre farm, and I took it out of the cupboard one day and he said, ‘You know, I always wanted one of them.’ I said, ‘Buddy, you got it.' So I gave my accordion away, but I wouldn’t give it to Snuffy.”

* * *

“We were stationed in Bremerhaven, and that’s when they put us on town MPs,” Elmer Forrest said. Elmer was the younger brother of Ed Forrest, a lieutenant in the 712th Tank Battalion who was killed in the war. Elmer was wounded in Europe with the 30th Infantry Division and after recovering was transferred to the military police. “And that was a mistake,” he said, “because we were all ex-combat men and they’re putting us on town patrol?

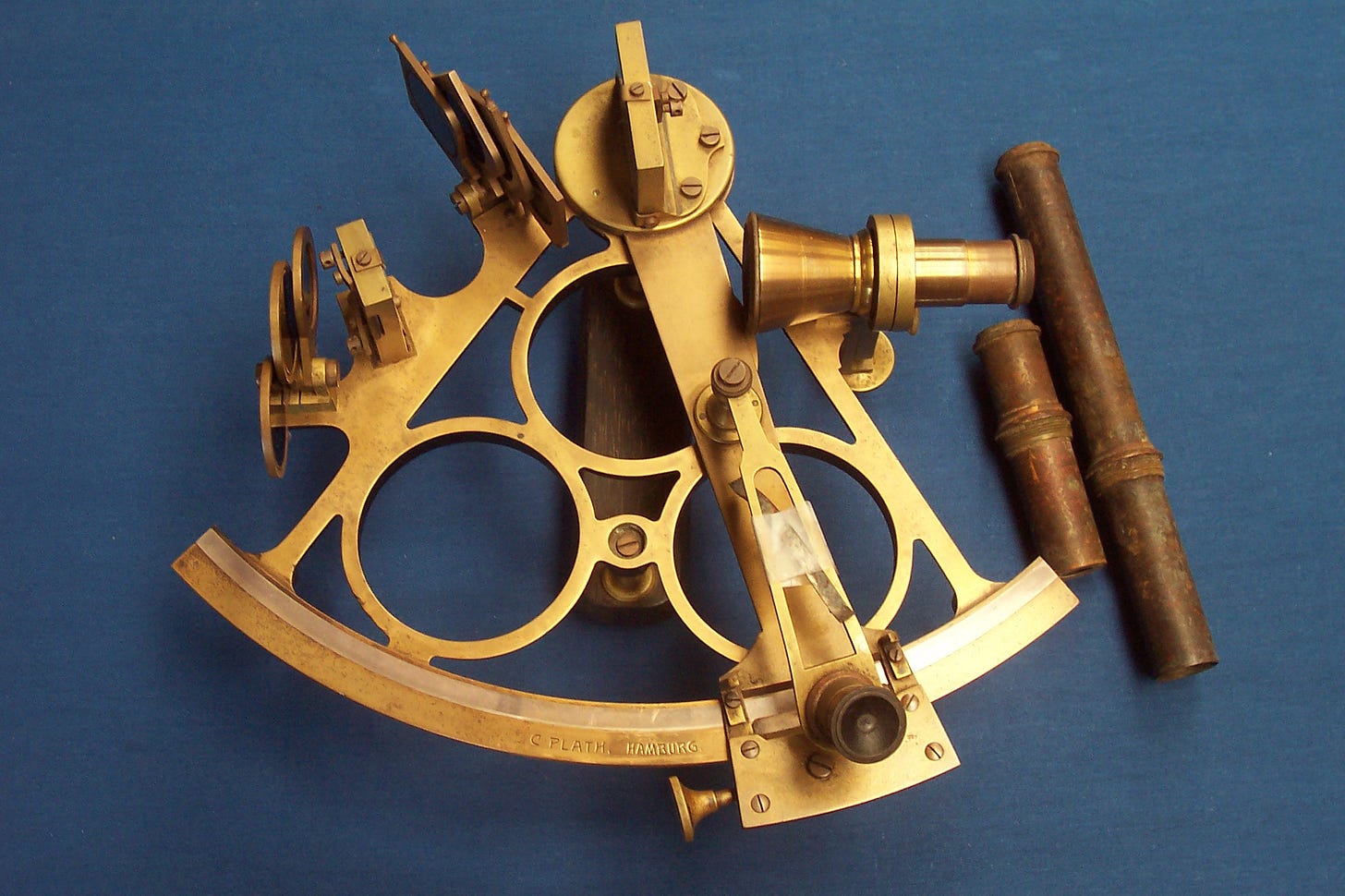

“I’ll tell you a funny what happened. We were in Bremerhaven and Hank Sokowski and I were on patrol in a jeep one night and of course we head for the waterfront because hell, we hadn't had any ice cream, we hadn't had any milk that was fresh, we had canned stuff. So we went on board this one boat and this guy we're talking to, I think he was the captain of the boat, he said, ‘You know, I've got a German working for me that's got a sextant [a navigational instrument for mariners],’ you know, one of these things that you hold. And he said, ‘He wants 12 cartons of cigarettes for it.’

“I said, ‘Well, would you give 12 cartons of cigarettes for it?’

"‘Gladly,’ he said. ‘I'd love to.’

“‘Good. ‘Where's this guy live?’

“So he told us. Now Hank and I, we get the jeep, we drive down to this guy's house, put on MP brassards and white hat, go in, oh, Jesus, who do we stop? ‘MPs.’

“‘Ohhh.’ So we went into his apartment, and I said, ‘I understand you have a sextant.’

“‘Nichts verstehe.’

“So we had to start looking for it. Well, we found it. He had a grandfather clock and down in the bottom of it was the sextant and a camera, which was verboten, they couldn't have cameras. So Hank said, ‘Oh, we'll take the whole damn thing, the heck with him.’

“I said, ‘Aw, let's give him at least a carton of cigarettes.’

“So we gave him a carton of cigarettes and told him to keep his mouth shut. We went back, the guy gave us the whole twelve cartons of cigarettes for that one sextant. Plus we had the camera, I forget what we did with the camera.”

* * *

Well, an accordion and a sextant are a little esoteric as “souvenirs” brought home by World War 2 veterans. The luger was the souvenir most coveted by combat veterans. At one point, when the 712th Tank Battalion was having difficulty replacing tanks that were lost in combat, Major Forrest Dixon told the battalion commander, Colonel George Randolph, that on a trip to ordnance, he could trade five lugers for five new tanks. (Dixon said Randolph would not go along with the plan.)

When I interviewed Dixon at his home in Munith, Michigan, I mentioned that Red Rose, a member of Service Company who attended most reunions, told me that one time Dixon encountered a dead German, but didn’t know that he was dead at the time.

“Oh, I remember,” Dixon said, chuckling, “I opened up the hatch and there was a German. We went to recover these tanks, but there was no particular danger at the time. This tank was in friendly territory. That is, nobody was firing at us. And you always look in your tank to see what’s inside. I opened up the hatch and there was a German. And I didn't know whether he was alive or dead, so I slammed the hatch down right quick. And I yelled to somebody, I said ‘Come on up here! There's a German in this tank!’ And then we kind of gathered that he was dead because there was no activity, so we quietly, or carefully, peeked in, and we saw that he was dead. We didn't evacuate the tank because there was a dead German in it; we just reported it to somebody , I think probably to the graves registration people, that there's a dead German in one of our tanks. But I did take a pistol off of him. He had a German luger on him.”