Battle fatigue. Shellshock. Call it what you will. A veteran of one of the 90th Infantry Division’s artillery units wrote and published in spiral binder form a memoir in which he described a sergeant breaking down under pressure. When the sergeant read the memoir and threatened to sue, the author had to re-do the memoir sans the offending passage and reissue it. Hence, I have in my “archive” two copies of the memoir. One other thing about that memoir, and this is why I love these first person accounts: When I went to my first reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I met three veterans who remembered my dad, two of them only in passing. A couple of years later, when I went to my first reunion of the much larger 90th Infantry Division, I met Duane Richter, who was a few years older than me, as I think he was two years old when his father, a forward artillery observer, was killed in action.

Just as I wrote to the newsletter of the 712th, Duane wrote to the newsletter of the 90th Division asking if anybody remembered his father, Captain James Richter. I forget how many responses he got, but it was north of 80, including the aforementioned memoir author who included a passage in his book in which he was on the telephone with Captain Richter when he was killed (during the same artillery barrage in Nothum, Luxembourg on January 9, 1945 that killed the 712th Tank Battalion’s commanding officer, Colonel George Randolph). According to the memoir, Captain Richter’s last words were “Excuse me, I have to duck.”

Which drew some criticism because some of the 90th veterans recalled Captain Richter as being fearless, whereas others thought that by that point in the war, after being under fire from D-plus 2 (June 7, 1944) in Normandy until January of 1945, he might have begun to be less fearless.

Rex Smallwood: Which brings me to Lieutenant Leo Hellman, who would be removed from command of the second platoon of Company C in the 712th Tank Battalion and replaced by Lieutenant Francis “Snuffy” Fuller. He was not the first member of the battalion to be overwhelmed by the stress of battle and he wouldn’t be the last, but when it happened to an officer the consequences were compounded.

In the second installment of this Memorial Day series I mentioned the death of Sidney Henderson and Rex Smallwood in the battle of the Falaise Gap but I didn’t go into much detail. This incident came up in a conversation at the 1993 battalion reunion in Orlando, Florida:

Aaron Elson: The second platoon was led by...

Otha Martin: Francis Fuller

Aaron Elson: What was he like?

Ralph Tambaro: Sort of a quiet type fellow.

Otha Martin: A real quiet little fellow. We had a man ahead of him, but he wouldn't fight.

Aaron Elson: Was that [Leo] Hellman?

Ralph Tambaro: Yeah, that's it.

Aaron Elson: What happened with Hellman?

Otha Martin: They transferred him to the quartermaster. The quartermaster handles supplies, they're way back, they don't even hear artillery.

Andy Rego: He broke down under fire. We were trying to close the Falaise Gap, and we were bivouacked, and they moved the second platoon out, and Hellman was the commander of No. 1 tank, and they were going down this road that led to the Gap. The Gap was an enormous valley down in there. And Hellman was proceeding up the road, and his tank got hit. When his tank got hit, Hellman bailed out of the tank. He never stayed to see if any of his men were okay or not; he came back to the company. He just claimed it was too god damn bad.

In that tank, the driver was a tall fellow from New York, named, I think he was being raised by a widow woman, Sidney Henderson was his name. Nobody ever knew what ever happened to Sidney Henderson. Did you ever hear anything about Sidney Henderson?

Ralph Tambaro: No.

Andy Rego: Nobody ever found out what ever happened to him.

Aaron Elson: Was he wounded?

Andy Rego: We don't know. He was never found. He must have been captured. If he got captured, we still don't know that. He was missing in action. Charlie Vietmeier was the gunner, he was from Pittsburgh, and Charlie broke down, and I've never seen, Charlie. He was sent out of there, and I never saw him come back to the company again. Wasn't it a guy by the name of Tolland, I think, was the bow gunner?

Ralph Tambaro: No, Smallwood. Smallwood got all cut to pieces trying to get out.

The following year, at the Cincinnati reunion of the 712th, I interviewed Don Knapp.

Aaron Elson: You were in Hellman's platoon?

Don Knapp: Yes.

Aaron Elson: Were you there when he was relieved?

Don Knapp: I was in back of him when he got nailed in the Falaise Gap. I seen the whole thing. I seen Smallwood in the ditch, dying. I jumped down and he was about gone, and I hollered for the medics. Then I looked into the tank, to see if Henderson was there, and that's when Henderson, no matter what anybody tells you, he got it there. Sidney Henderson. I have a letter that was printed in the 712th bulletin from his aunt, the old lady, they wanted to know about her Sidney that she loved so much. He was the driver of Hellman's tank.

Aaron Elson: Hellman got hit in the Falaise Gap?

Don Knapp: Yes.

Aaron Elson: Did you see the tank when it was hit?

Don Knapp: Yes. Monty [Sergeant William Montoya] was in front of us. I was the third tank. He came up on a rise, WHAM! There was an antitank gun, okay, and I saw them APs [armor piercing shells] coming, they went right through him [Hellman’s tank]. And my, oh yeah, you could see those APs, they were red-hot, coming at you. It's not like a panzerfaust, that's like a football. I saw Hellman come out, a big man. I can always see that silhouette. And I never saw anything else on the tank, we were so busy backing up.

Sheppard [Captain Jack Sheppard, the C Company commander] came and told me, "Hellman's taking your tank." So I went on the back of the tank, sort of on the rear, sitting all by myself with a Thompson submachine gun.

The next day we're creeping up, back to that position. The antitank gun was gone, so we start to pull around, very slow, and I look over and I see Smallwood laying in the ditch.

Aaron Elson: He was still alive?

Don Knapp: Yeah. I jumped down, because I thought I saw him breathing, and he was, I could see him breathing, and I hollered "Medic! Medic!" And then I got back in the tank, which had stopped enough for me to get on.

Aaron Elson: Was he speaking?

Don Knapp: No, just breathing. And I told Sheppard, he said, "No, he was dead."

I said, "No, he was breathing."

So we got into the Gap, shooting away.

Aaron Elson: What about Henderson?

Don Knapp: I presume. Nuce [Charles Nuccio] told me they were still carrying him as missing in action. They couldn't find his body.

So anyway, we got up to the Gap and we're shooting. I relieved my gunner, Johnny Clingerman, because I wanted to get some shooting in.

Aaron Elson: You relieved Clingerman because you wanted to fire? What was it like, a shooting gallery?

Don Knapp: All down there, 2,000 yards. I remember aiming at a motorcycle and I think I got it, somebody got it. And several times, that was Von Kluge's Seventh Army. [Later] we went down [into the Gap] and then they called it the Valley of Death; the stink was something terrible.

Aaron Elson: When you were doing that, did you have a feeling that this is going to be like a historic event?

Don Knapp: No. I was just happy that they weren't shooting back at us. Once they were throwing some rounds in, and Helmut Speier, the mess sergeant, did you ever hear about him? We called him Gestapo, Speier was up there, he wants to shoot at them; he brought some meat up for us, and he caught some shrapnel in the butt, I think that's the last we saw of him. So we get him in an aid truck to take him back, and a German asked him for a cigarette, and somebody told me this, I didn't hear it, Speier says, "First you serve with Hitler, and now you want a cigarette?"

That was the Gap.

Sidney Henderson’s name is on the Wall of the Missing in the Brittany American Cemetery in France.

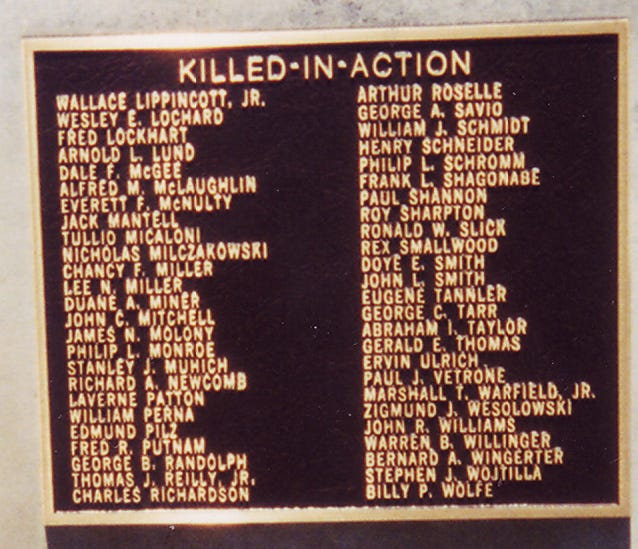

Doye Smith: This one’s a mystery. Private Doye Smith of B Company was killed on Sept. 27, 1944. At the time, B Company was in a non-combat situation. Also, he is not mentioned in Louis Gruntz Jr.’s book “A Tank Gunner’s Story,” in which his father recounts the deaths of many members of B Company. Doye’s great-nephew Brian Smith has been obsessed with learning how his great uncle died, and has had no success despite enlisting the help of researchers on both sides of the Atlantic. Doye Smith was born on Feb. 25, 1924 and is buried in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, National Cemetery.

John L. Smith: This one, too, is a mystery. This is from HonorStates.org:

Some records indicate [him as] being held as a prisoner by Germany at a location known as Rennes Military Hospital Rennes France. Died on July 21, 1944, as a Prisoner of War under German control.

I can only venture a guess that he was gravely wounded and captured during the battle for Hill 122, which ended on July 12, 1944. Private Bob Levine of the 90th Infantry Division and Sergeant Kenneth Titman of the 712th were both wounded and captured during the battle, and both were sent to a school in Rennes, France, that was converted into a military hospital. They were liberated a few weeks later by the 8th Infantry Division.

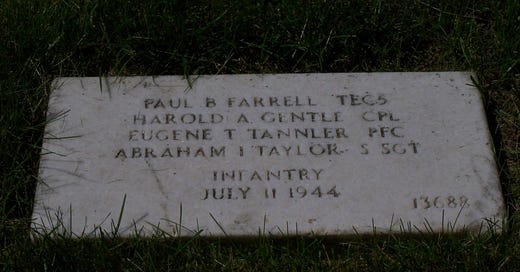

Eugene Tannler: Eugene Tannler was the loader in the tank commanded by Sergeant Abraham Taylor in which all five crew members were killed when the first platoon of Company C was ambushed in the battle for Hill 122 in Normandy. Although nine of the 20 crew members in the four-tank platoon were killed, Tannler’s was the only one in which the entire crew perished. Tannler’s original tank commander, Judd Wiley, was evacuated the day before the battle after suffering a leg injury when a liberated German “Kettenkrad,” a vehicle with a motorcycle front and a tracked compartment in the rear, tipped over; and a hand injury when a hatch cover slammed down on his fingers while he was clutching the rim of the hatch as the tank went over a hedgerow.

When I interviewed Wiley at his home in Seal Beach, California on Oct. 2, 1994, his wife, Donnis, said that Judd had a serious case of survivor guilt.

Aaron Elson: Your wife has said that you felt what would be called survivor's guilt.

Judd Wiley: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. Oh, I felt terrible. I would have loved to have died with my men. Two months later or three months later when I found that out I was so, I, it's still a horror to me when I think of it, us, we never had an argument, none of us. It was the only tank probably in the whole damn battalion where everybody liked everybody else. We never had any problems, and that's why we won so many awards, when we were in England.

Tannler was from Scranton, Pennsylvania. Lieutenant Jim Gifford went into the tanks of Lieutenant Jim Flowers’ platoon, and except for bone fragments he was only able to find a ring that belonged to Tannler. It was placed with his belongings, but never made it to his family.

(more to come)

Let me know with a comment if you think that this series about the 99 members of the 712th Tank Battalion who were killed would make for an interesting book. Tentative title: “Some Gave All”