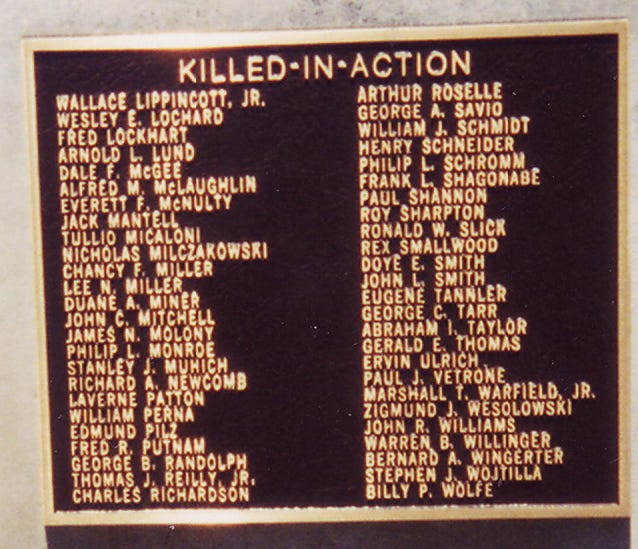

Marshall Warfield: “It was Sunday morning, we were sitting in Briey” on Sept. 17, 1944, “and we were looking for a way down the railway track to take some tanks,” Ken Fisher, the platoon sergeant who would take command of the 712th Tank Battalion’s recon platoon after Lieutenant Marshall Warfield’s death, said when I interviewed him in 1996.

“Warfield, [Tim] Smith and [Patrick] Reilly were looking for a way to move tanks.”

This was the period when the battalion and the 90th Infantry Division, to which it was attached, were stalled on the west bank of the Moselle River probing for a place to cross in force.

“They had cleared an outpost,” which was probably the last 90th Infantry Division outpost in friendly territory, Fisher said. “Reilly and Warfield were on this one track and Smith was on the other side of the track, and a machine gun opened up on them. Reilly was killed instantly. Marshall Warfield got back to an aid station, and he died in the aid station, of shock. The reason I know this is because Smith was there and Smith would never abandon a living person, and the aid station wasn’t that far away.

“The doctor personally told me he died of shock. His wound would not have killed him. But he told me, now this is true, he said that this is it.”

“Warfield always said, ‘I know if I get hit I’m gonna die,’ Fred Steers said at the Medford, Oregon reunion in the late 1990s. “When we went overseas, Marshall was the commander of the reconnaissance platoon. I was a corporal at that time, and one day he was assigned a daylight reconnaissance mission. Ordinarily, he always asked me to go with him wherever we went, because he liked the way I handled my rifle. I was a pretty good shot, I guess. But this day he said, ‘I don’t want you to come with me.’ So he took another corporal, Patrick [Reilly] and Tim Smith. And they took off on this mission.

“Later that afternoon, Smitty came back, and he’s the only one that came back. Reilly got killed right on the spot. Warfield was shot there too. Smitty got him back to the aid station, but he died there.

“Later, Smitty and I were assigned to go out there and see if we could find Tim. We went out there and found where they’d took off, and Smitty wouldn’t let me go with him. He said, “You wait here.” He was a staff sergeant, and I was just a corporal. He anchored me right there and made me stay there. So I waited for him, and he was gone for a good half hour, and I heard a rifle shot. And I just was so afraid it was him. I was just getting ready to take off and go down there anyway, and here he comes back. He’d picked up Reilly’s pistol and he handed it to me, and I carried that for quite a while.”

Marshall Warfield was from a prominent Maryland family. His brother Albert was the commanding officer of the Maryland National Guard during the turbulent 1960s, and among his distant relatives was Wallis Warfield Simpson, the American socialite for whom King Edward VIII abdicated the throne of England.

Which brings me to my interview with Marshall Warfield’s widow, Olga, pronounced “Ahlga.”

In the late 1990s I interviewed Marshall’s widow, who never remarried, at her modest home in Oakton, Virginia. It was one of my most fascinating interviews ever, and while I have never transcribed it, I used a portion of the interview for episode 27 of my podcast, War As My Father’s Tank Battalion Knew It, in 2020. The podcast has been on hiatus for the past two years and I hope to revive it soon, but more than 100 episodes are still available for free at sites like Spotify, Itunes and Audible, although I guess Audible might have a slight charge. But here is a copy of Episode 27, at the end of which I included audio of my conversation with Fred Steers, who was a corporal and then a sergeant in Marshall’s reconnaissance platoon.

Olga Warfield interview excerpt:

Zigmund Wesolowski: In one of the ironies of war, Zigmund Wesolowski was so shaken up on the battalion’s first day of combat when his tank was struck by a round from an antitank gun that he was transferred to Headquarters Company. That was on July 3, 1944. On Christmas Eve of that year, he was riding in a jeep that ran over a mine and was killed. It’s one of the tragic cliches of war that when it’s your time it’s your time, and there’s little or nothing you can do about it.

John R. Williams: Another B Company tanker whose name I didn’t recognize, but can thank the late Louis Gruntz Jr. for the following passage in “A Tank Gunner’s Story”

On January 10, 1945, Dad’s best friend, John Richard Williams, was killed in action during the Battle of the Bulge. Almost a year had lapsed since the married men of the 712th told their wives goodbye at Fort Jackson. Unfortunately for Richard and Opal Williams, their goodbye occurred during a period of marital discord. Dad had written Mom in November of 1944 and told her that he had asked Richard if he had ever heard from Opal. Richard’s reply was that he had not written anything in the past seven months. Dad stated: “A day or two before he (Richard) got killed he came to me, and said, ‘Louie, I wrote Opal and made up with her and I told her we are going to try and make it together, so when I get back we are going to go back together.’ He wrote her a letter and said that things were going to be different but he never did come home, he got killed two days after that.”

Warren B. Willinger: Warren Willinger of B Company was killed in action on August 7, 1944, in Ste. Suzanne, France. Again, from “A Tank Gunner’s Story”:

Sgt. Warren Willinger was tank commander, Dad [Louis Gruntz] was the gunner, Lloyd Sparks was the driver, Dee Johnson was the assistant driver, and a replacement private, William Land, who joined the Company on July 14, was the loader. Dad’s tank had taken over the lead position in the advance when the other tank in the squad got stuck in the mud off the main road into town.

In war, the farther forward you are, the more you know about the immediate situation but the less you know about the overall situation; the farther rear you are, just the opposite is true. As Dad explained, that truism was in effect on that day:

“We were at the top of the hill coming this way. We thought they were firing artillery at us, so what we did was we fired a shot at the steeple of the church and knocked half of the steeple off (to knock out any enemy artillery spotter).”

Up until then the infantry was walking close to the tank; as the tank proceeded, the infantry stayed behind under cover.

“Then we proceeded with the tank up this road here and we took the road on the left next to the wall of the cemetery. We were firing at Germans running across the street in Sainte Suzanne (running from right to left perpendicular to the direction the tank was traveling). When we were firing we got radioed from the officer in charge in the back and said we were firing on friendly troops and we stopped firing. We got up to the wall — a few yards up that road to that cemetery way and we stopped.

“We saw the Germans still running across the road going in toward the church, toward the center of town. We started firing again. They called back again and said you are firing on your own troops. So I told Willinger, ‘You tell them if we are firing on our own troops then they had German uniforms on.’ So we ceased firing. Willinger was sticking his head out (of the turret). He was afraid someone was in the cemetery and he grabbed a hand grenade. […] He may have seen something in that graveyard. When we (stopped firing) the bazooka came out of the cemetery and hit the tank.”

The German soldier behind the stone wall in the cemetery was armed with a Panzerfaust and, at that close range, he hit the tank turret.

“The turret top was up and it (the shell) hit the top of the turret and it melted and all the steel went all through the tank. Willinger was standing up (behind me) and he got hit in the head and it came over his shoulder and hit me in the back. He fell down. He fell on me, not on top of me, and fell down to the (bottom of the tank). A ball of fire went through the tank, the tank lit up you almost went blind with the light. I jumped out and I told everybody, ‘Get out, let’s get out.’ We couldn’t proceed any further and were afraid it (the tank) was going to blow up. Willinger was dead.”

Bernard Wingerter: This is one of those mysteries that may never be solved. Bernard’s date of death is listed as August 18, 1944, and he was in C Company, yet the only member of C Company killed on that date was Rex Smallwood; and Sidney Henderson, who was listed a missing in action until he was declared dead. The inscription on Corporal Wingerter’s Find-a-Grave page reads: “The seventh child, sixth son, of Conrad Carl Wingerter and Elizabeth Ann Schmaltz, he was the twin of Fred Conrad Wingerter. He enlisted in the US Army in Spokane, Washington on July 28, 1943 and assigned to the 712th Tank Battalion. He was the first of two sons killed in action during World War II.”

Stephen J. Wojtilla: Pfc. Stephen Wojtilla, of Farmington, Connecticut, was one of nine members of the first platoon, Company C, killed in the battle for Hill 122 in Normandy.

Billy P. Wolfe: I’ve probably written more about Billy Wolfe than about any other member of the 712th Tank Battalion, with the exception, perhaps, of Lieutenant Jim Flowers. His story is featured in all three editions of my book “Tanks for the Memories,” An 18 year old replacement who was with the battalion for only two weeks, Billy was killed in the battle at Pfaffenheck, Germany on March 16, 1945.

"I don't want to choose an occupation now because I am not sure what type of work I want,” Billy wrote in a high school essay. “I will soon be of draft age and may be put in the service. After serving my time my views may be vastly changed. I may, if the war don't last too long, want to take a little more schooling. Or I may get specialized training from Uncle Sam which might be my life’s work..."

“It was his life’s work,” Billy’s sister Madeline Wolfe Zirkle said.