John C. Mitchell: Often when I’m asked what got me interested in preserving the stories of World War II veterans, I say that at the very first reunion of my father’s tank battalion I went to, in 1987, I saw a veteran telling a story and listened in. Although I missed the first part, I was glued to the spot until the veteran, who I later learned, was Wayne Hissong, finished. Later, I asked if he would tell me the story from the beginning, and he was happy to oblige.

It wasn’t a story about combat, at least not with all the details that often accompany a war story. It was about how Wayne entered the service with three friends from his hometown of Argos, Indiana. One of those friends was John Charles Mitchell. Wayne and John stayed together through the horse cavalry, through its mechanization with the 10th Armored Division, and when the 712th was broken out of the 10th as an independent battalion, Wayne was assigned to Service Company as a truck driver, and Mitchell a tank driver in B Company.

Mitchell was killed on the battalion’s first day in combat, and the story I overheard Wayne telling was about all the things he did upon returning home to the small town of Argos, Indian, to avoid facing his friend’s mother, who owned a dry goods store downtown. Finally, Wayne’s father said “Son, we’ve got to go downtown and see” Mitchell’s mother.

“I couldn’t tell her very much,” Wayne said. “He was a tank driver. At one point he was considered one of the best tank drivers in the battalion.”

That was the end of the story Wayne told. But it wasn’t the end of the story.

When the first edition of Tanks for the Memories came out, in 1994, Paul Wannemacher, the battalion association secretary, got an angry letter from Orval Williams of Macalester, Oklahoma. Orval was upset, and rightfully so, that I had all but ignored the battalion’s B Company in the book. My father was in A Company, the most ardent storytellers were in C and Service Companies, and I’d only spoken with a few B Company veterans at the reunions.

I was planning an interviewing trip in 1994, and told Paul I would get in touch with Orval and add Macalester to my itinerary.

Orval was a wiry fellow, 80 years old in 1994, and, like Otha Martin, who also lived in Macalester, had spent some time as a guard at Macalester State Prison. We drove past the prison and he wanted to show me the museum with all the makeshift weapons that were confiscated, but it was closed that day.

When we sat down to talk, he was apologetic.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Elson,” he said, “and there’s one thing, I want to apologize to you for that old nasty letter I wrote.”

“I’m glad you wrote it,” I said, “because it made me realize that I should have been more thorough.”

“Well, you see, now you might imagine, just take if you’d have been in my place, and I’m anxious to get this book, and I’ve still got it. I wouldn’t take for it. There’s good reading in there. But when I keep reading on and mentioning A Company, and C Company, and D and Headquarters, and no B Company, it’s kind of like talking about your folks. And then, we’re like a family when we was in there together. Some of them old boys I loved ‘em like a brother, and I had a tank crew, I just, I’d have done anything for ‘em. And I thought a lot of Sergeant Diel, but when he did what he did the day we got knocked out, I care not to talk to him or even see him.”

In essence, at St. Jores in Normandy, Sergeant Dan Diel’s tank, in which Orval was the loader, became separated from the rest of his platoon, and as it approached a curve in the road, there was a German tank just around the bend.

“He took our tank and completely left the whole outfit and when we got knocked out and I got out of that tank I couldn’t see another tank nowhere,” Orval said. “He led us up over there and broadsided us right across the road right at a curve, and that first shot that tank fired at us missed us. I heard it and I pulled my periscope left, and I told Sergeant Diel, ‘Someone took a shot at us from the right side.’

“He said, ‘Oh, that was a shell burst.’

“And I said, ‘Sergeant, don’t tell me. I know a shell burst from a gun firing,’ and I turned my periscope around and I’m looking right down the tube of that, just, less, about a half a block from us. I’m looking right down the tube at it, and boy, about that time they let her fly again. And I was in that tank when two shells come through it, and they shot it again. Of course the first shot killed Mitchell. I could see him, he was right in front of me. Just about half his head was gone.”

Wait, what? “Mitchell was John Mitchell?” I asked. I was like, what are the odds? No wonder, I also thought, Wayne Hissong could tell Mrs. Mitchell only so much. In all likelihood he would have known far more of the details.

“John Mitchell, my driver, well, you'd like him when you first see him, he was that type of guy,” Orval said. “He was a big guy, he probably weighed about 220, 6 foot tall, and a young guy, just pleasant to be around. And that first shot killed him. The first shot got me, knocked me off my seat, tore three inches of little bones out of my left hand.”

Orval, whose war was over that first day of combat, said he never went to a reunion because he didn’t want to see Sergeant Diel (who later received a battlefield commission and was a lieutenant). But I knew that if Orval had gone, the anger that roiled inside him all these years would have dissipated in a moment, and he would have accepted Diel’s explanation for what went wrong that day.

“The German tank knew where we was at, and we didn’t know they were there,” Diel said when I spoke with him at the reunion only a few days later [the reunion was the final stop on my interviewing trip]. “I looked up and seen the tank comin’ and I hollered ‘Tank!’ Well, when I hollered ‘Tank!’ it was automatic that you took, we had a high explosive shell in the breech and the loader opened it up to get rid of the HE and put in an AP [armor piercing]. And that was the wrong thing to do. It was the right thing for the way we was trained. It was the wrong thing for the circumstances, because while he was unloading and reloading, they got the shot in. And if we’d have hit ‘em with an HE, even though it wouldn’t have hurt ‘em, it might have stunned them enough or slowed them down from the debris and the smoke that we could have got another shot in, but it didn’t happen that way.

“But I always thought that if we’d have fired a shot instead of going through the reloading motions, if we’d unloaded the gun just by pressing the trigger, it might have saved him. But I also am a believer that it don’t make any difference where you’re at when your time’s up, you’re going.”

James M. Molony: According to Find-a-Grave, James N. Molony was killed on Jan. 21, 1945. His remains were repatriated in 1948 and he is buried in Covington, Kentucky. He was 19 years old, and probably had not been with the battalion very long as a replacement.

Philip L. Monroe: From my 1992 interview with Pfc. Bob Rossi of C Company’s third platoon: “Monroe was a replacement officer in the Third Platoon. March 21. He was leading the platoon. First of all, he wasn't a tank-trained officer; he was a maintenance officer. They made him a tank officer, and he was riding sitting up on the turret, and [Lieutenant Max] Gibson told him "Get down in that turret." He said, "only your head sticks out and that's too much." So this one particular day that we encountered a lot of fire, Lieutenant Monroe got out of his tank to disperse the infantry, and one mortar came in and wounded him. ]William] Frink tried to get out and save him; another mortar came in and finished Monroe off.”

According to Find-a-Grave, Lieutenant Monroe is buried at the Lorraine American Cemetery at St. Avold.

Stanley J. Muhich: From my 1996 interview with Cleo Coleman of B Company:

Oh, you were talking about Muhich. I was right beside him, the next tank over. I don’t remember the town now, it was a small village, but anyhow a shell got jammed in the chamber, so you’ve got a big rod; you have to get out there at the end of the barrel and push it out. That’s what he was doing, when a sniper got him.

They loaded him up and we moved back to this little town; we stayed indoors, so we had cover at night. That evening there was a sniper, he was bound to have been a sniper, he had a camouflage uniform on, and one of our boys — Muhich was one of his best friends — and I seen him march this prisoner out behind a stone wall, and close the gate. I didn’t pay much attention, but I heard a gun fire. And I thought something had happened, he’d done something to him, and he came out of that gate and he was white in his face.

One boy says, “He shot that prisoner,” the sniper. He said, “Let’s go in there.” And we went in there; he had a hole there, it was between his eyes. Nice looking man. But I never did say nothing about it.

Later on, after I got a discharge and came home, I got a letter from Muhich’s sister. I believe he lived in Milwaukee. She wanted to know how well I knew her brother, and did I know how he got killed. And I wrote her back and told her just exactly how he got killed. She wrote me another letter; she said, “Did you ever hear of Stan ever saying if anything happened to him, he wanted to be buried over there?” I wrote her back and told her I never heard him say anything. I said we didn’t talk about things like that. So I don’t know what happened. He was a cavalry man.

According to Find-a-Grave, Stanley Muhich was repatriated and is buried in Aurora, Minnesota. He was 31 years old.

Richard A. Newcomb: A private first class in Headquarters Company, Newcomb was killed in the jeep that ran over a mine on Christmas Eve, 1944. He was 30 year old, and is buried in Milton, Massachusetts.

Laverne Patton: Laverne Patton was one of nine members of Lieutenant Jim Flowers’ first platoon, Company C who were killed on July 10, 1944 during the battle for Hill 122.

William Perna: I was unable to find any information on William Perna. He was not listed in the battalion roster.

(To be continued)

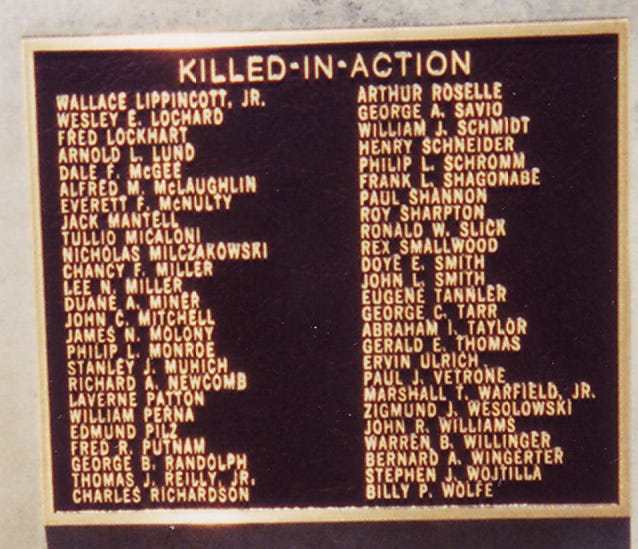

While the world focuses on the chaos and hoopla surrounding the 80th anniversary of D-Day, I’m stuck on Memorial Day and determined to see this through, to honor the memory of the 99 men of the 712th Tank Battalion who were killed in World War II.

Not to ignore D-Day completely, though, please check out my book “The D-Day Dozen” at Amazon, available in print and for Kindle.