Memorial Day 2024 Part 7

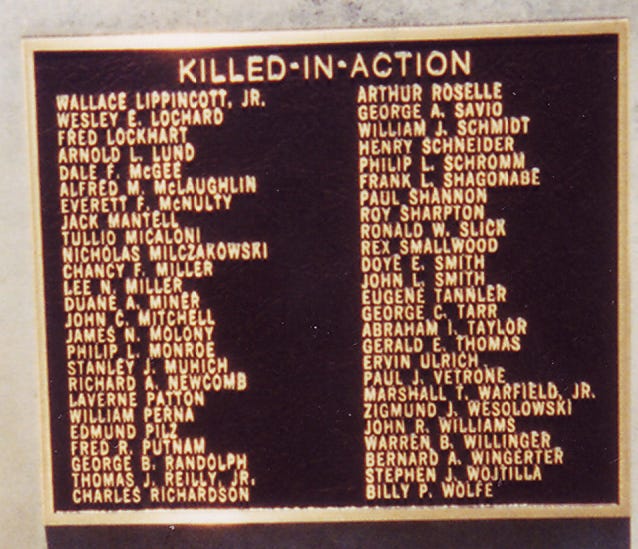

A look at the names on a tank battalion monument

On Memorial Day, Pearl Harbor Day, the anniversary of the raising of the flag on Mount Suribachi, American Legion Post 2 of Bristol, Connecticut, and the World War 2 Legacy Foundation honor the occasion by ringing the Captain’s Bell of the destroyer USS Kidd as they read the names of the fallen from the state. Incidentally, while the Kidd was the only U.S. Navy ship authorized to hoist the Jolly Roger, it was named not after the famous pirate but after Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd, who perished on the bridge of the battleship Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Admiral Kidd’s widow approved of the flying of the skull and bones, and said her husband’s nickname was “Cap”.)

This Memorial Day I thought I would go down the list of 99 names on the monument to the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served, to give myself a sobering reminder that despite writing extensively about the battalion, there were many of the battalion members who died in World War 2 I still knew nothing about. Many of those names were in the battalion’s B Company. Fortunately, Louis Gruntz Jr., whose father was in B Company, wrote a book about a trip he took to Europe with his dad in which the elder Gruntz related a great deal of the company’s history. Between Louis’ book, “A Tank Gunner’s Story,” and my own interviews, I found I could say a little something about many — but still not all — of the names on the monument.

The last name in Part 6 was that of Fred Putnam. The first time I heard his name was in my interview with Jim Gifford, who had a photographic memory but on occasion may have done a bit of embellishing, like the time he said he found a Reader’s Digest in the rubble of a crashed glider in Normandy and cut out two small American flags and placed them inside the handle of his .45 caliber pistol. When he was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge, he said, he handed the pistol to Bob Rossi and told him to hold it until he came back. Rossi mentioned the pistol because after his next tank was knocked out he was running and Lieutenant Gifford’s pistol fell down his pants leg and he was afraid of being captured with it. I asked him about the American flag cutouts and he said the cutouts weren’t American flags but rather were pinup girls.

Fred Putnam was from Albany and Gifford was from Gloversville, New York. Jim said that after the war he went to visit Putnam’s mother and told her he was buried in a little village cemetery near a church. This is understandable, I mean, what is he going to tell her, that her son was blown to pieces by an armor piercing shell or that he might have burned inside a tank? I was interviewing Don Knapp, a tank commander in C Company, when he described the battle in which Putnam was killed. He had just been speaking at the reunion with Ralph Tambaro, who was the driver in Putnam’s tank.

Don Knapp: Tambaro said to me, here [at the 1994 reunion in Cincinnati], and I hadn't seen him since, I said, "We were on the side of a hill, and we were putting brush on to camouflage," and I heard "Whang!" His tank was just up above mine, higher on the hill, sideways, and I look out and in the mist I see a German tank, maybe 2,000 yards away, and I seen another flash, and as I seen the other flash Tambaro goes running by, and he had blood and stuff all over him, and it was the bog [bow gunner/assistant driver] that caught it.

Aaron Elson: Putnam?

Don Knapp: Putnam, yes. And I said to myself, you know, in your subconscious mind, "How the hell is he running with all his guts all over him?" But it wasn't his, it was the guy next to him. He maybe caught a little. But I said to Babe [Wes Harrell, Knapp’s driver], "Never mind the goddamn brush, let's get the hell out of here." So we pulled out, with brush and all, because I think if we'd have pulled up on that hill we'd have got nailed too because I don't think a 75 would have taken him out, because he was shooting an 88 and an 88'll take us out.

I remember Tambaro, and I said to him, I wanted it cleared up, "You were the driver, weren't you?" And I says, "Who was your bog?" And he could not think of it, and it finally came to him, and he said "Putnam." And, you know, when he left here, he's not a very demonstrative person. Wrapped his arms around me.

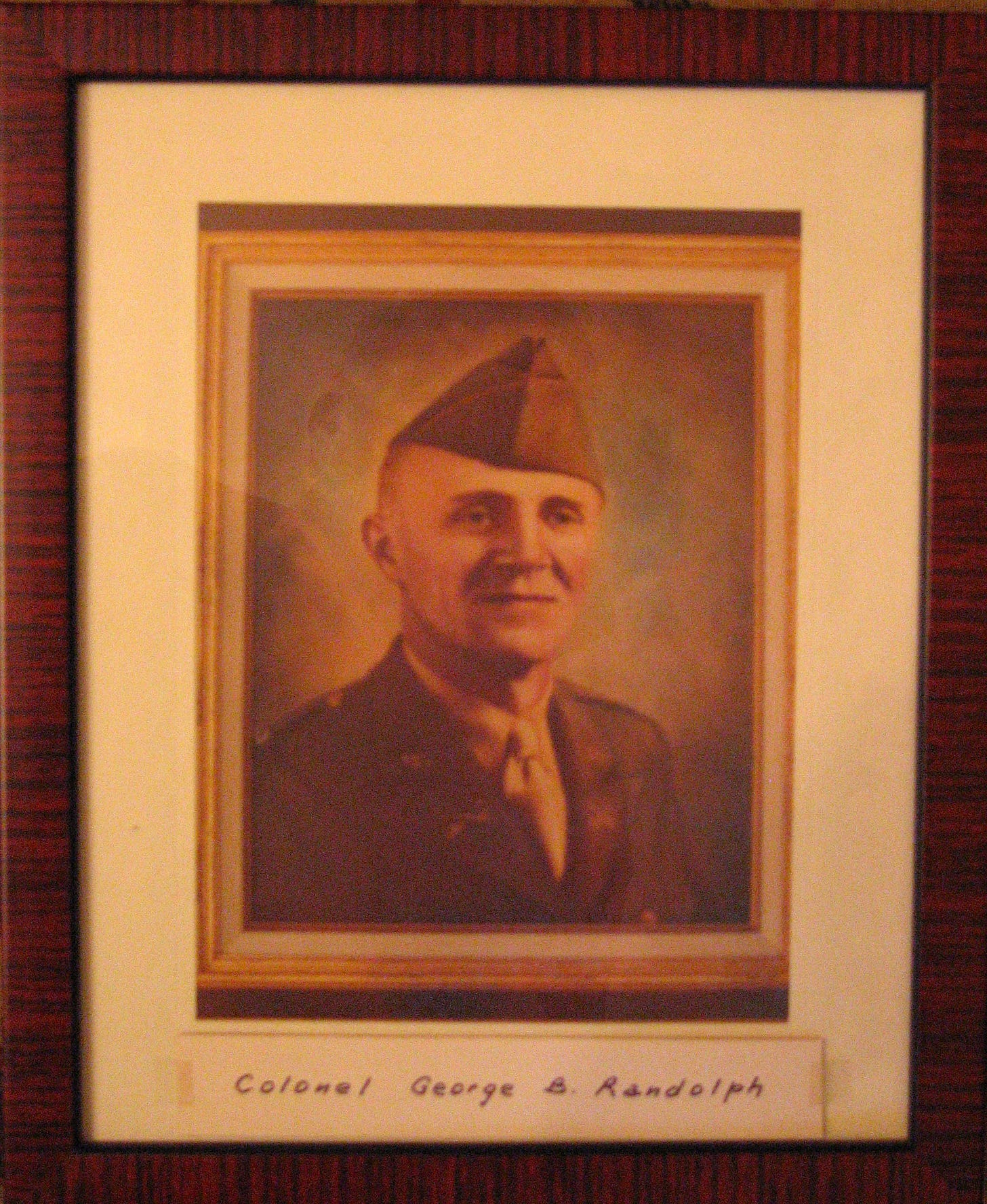

George B. Randolph: No death hit the 712th Tank Battalion harder than that of Colonel George B. Randolph on January 10, 1945, during an artillery bombardment in Nothum, Luxembourg. “Here lies a colonel by a tank, read the caption in the Saturday Evening Post [it actually was a destroyer]. A high school math teacher from Montgomery, Alabama, with a wife and two sons, Colonel Randolph took command of the 712th on June 6, 1944, while the battalion was still in England, after the battalion’s officers all but mutinied against the original battalion commander, Whitside Miller. Randolph went on to become one of General George S. Patton’s most respected officers.

Captain Jim Cary, the B Company commander who would be wounded shortly after Colonel Randolph was killed, was tasked with relaying the information to the battalion’s second-in-command, Major Vladimir Kedrovsky. Upon reaching Kedrovsky by telephone, Cary said: “George Kitten.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Do you understand?” Cary asked.

“Yes,” Kedrovsky replied.

Of all the code words in all the wars, kitten was the word for killed.

Kedrovsky became the battalion’s third and final commanding officer.

And while third and fourth hand information is not always reliable, when the battalion’s veterans commissioned a portrait of Colonel Randolph, it was turned down by one of his sons, who, according to Major Forrest Dixon, felt his father had abandoned him by getting killed. It is among my failings that I never was able to locate a family member or get any verification of this.

The portrait was donated to a museum in Diekirch, Luxembourg, where it hangs today.

While the battalion anecdotally had one of the best maintenance records of any tank battalion in the war, things did not look good in its early days of combat. Forrest Dixon, the battalion maintenance officer, recalled meeting with Colonel Randolph after the third day of combat. On the first day the 712th, which started out with about 70 tanks, lost almost half of them. Not all were destroyed; some were tipped over or bogged down or damaged but salvageable. On the second day almost half of the remaining tanks were knocked out or damaged. And on day three almost half of those that were left were incapacitated. Dixon recalled telling Colonel Randolph the battalion might not last another day.

On the contrary, Dixon recalled Colonel Randolph, the math teacher, saying, “If we lost half our tanks on the first day, and half of those remaining were lost on the second day, and half of the remaining tanks were lost on the third day, and we lose half of those that are left the next day, we should be good for several days.

Do your math homework, kids.

The 712th Tank Battalion’s tanks lasted for 311 days in combat and nearly finished the war with more tanks than it started with, but that’s another story.

Thomas J. Reilly, Jr. During September of 1944, the 712th Tank Battalion was sending small parties across the Moselle River, probing the German defenses and looking for a spot for the battalion to cross in force.

Fred Steers of Florence, Oregon, who was a sergeant in Headquarters Company, recalled Reilly as Tim Reilly. On September 17, Steers said at the battalion’s Medford, Oregon reunion in the1990s, Lieutenant Marshall Warfield “was assigned a daylight reconnaissance mission. Ordinarily he asked me to go with him wherever he went because he liked the way I handled my rifle. I was a pretty good shot, I guess. But this day he wouldn’t take me. He said, ‘I don’t want you to come with me.’ He took another corporal [Steers was a corporal at the time] and Tim Reilly. Joseph Patrick was the corporal. And they took off on this mission. And later that afternoon, Patrick came back. He’s the only one that came back. Tim got killed right on the spot. Warfield was shot there, too. Patrick got him back to the aid station, but he died there.”

I’ll have more on Marshall Warfield and my interview with his widow further down on the Honor Roll.

“Smitty [Eugene Smith] and I were assigned to go out and see if we could find Tim,” Steers said. “We went out and found where they’d took off and Smitty wouldn’t let me go with him. He said, ‘You wait here.’ He was a staff sergeant and I was just a corporal. He was gone for a good half hour and I heard a rifle shot. And I just was so afraid it was him. I was just getting ready to take off and go down there, and here he comes back. He’d picked up Tim’s pistol and he handed it to me, and I carried that for quite a while. He’d found Tim and they finally got him out of there, but Smitty couldn’t get him out then. I asked him about the rifle shot. He said he heard it, but it wasn’t fired at him.”

Charles Richardson: At the 1994 reunion in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, I recorded a conversation with three veterans, Tom Wood, Bob Atnip and Neal Vaughn, all of A Company. The transcript had a lot of names I didn’t recognize at the time and Tom Wood spoke kind of fast and the transcript has a lot of unintelligibles, but here is what I found:

Tom Wood: I don't recall exactly where it was, but an 88 hit us, and when he [Sergeant Greener, his tank commander] got out of the tank, why, then they started putting HEs [high explosive] through the trees, and they got him, and they got my loader.

Aaron Elson: He was killed?

Tom Wood: No, he wasn't killed there. But the last time I laid eyes on him he had his hip blowed open, his shoulder blowed open, and he was trying to crawl around behind the tank, and they started backing up at the same time; we thought, ohhh, there he goes, but we hollered loud enough the tank driver stopped. And that's the last time [I saw him], of course. He lived, though, after that. He died here in the States.

Aaron Elson: Sergeant Greener, was he the platoon sergeant?

Tom Wood: He was the tank commander.

Aaron Elson: And the loader was?

Tom Wood: Charles Richardson, Burkesville, Kentucky, and he was killed right there in front of me.

Aaron Elson: Was that one of the first days in combat?

Tom Wood: No, it was after the breakthrough. We got hit by an 88, I think, I'd say about 80 yards. It hit us a glancing blow, otherwise we'd have been Katy bar the door.

(to be continued)

I’d like to welcome all the new subscribers from the Reading, Pa., World War 2 Weekend at the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum. Yes, MAAM, this is one of the premier World War 2 re-enactment events. The weather was perfect and the crowds were awesome.

This weekend I’ll be at the Greenwood Lake, New Jersey, Airshow, another great three-day event with two nights of after-dark aerobatics and fireworks.

And if you’d like to read the earlier Memorial Day posts, click on the central button in the filter, which says “most recent.”