More on spark plugs

712th Tank Battalion had "the best so and so maintenance in the whole such and such army"

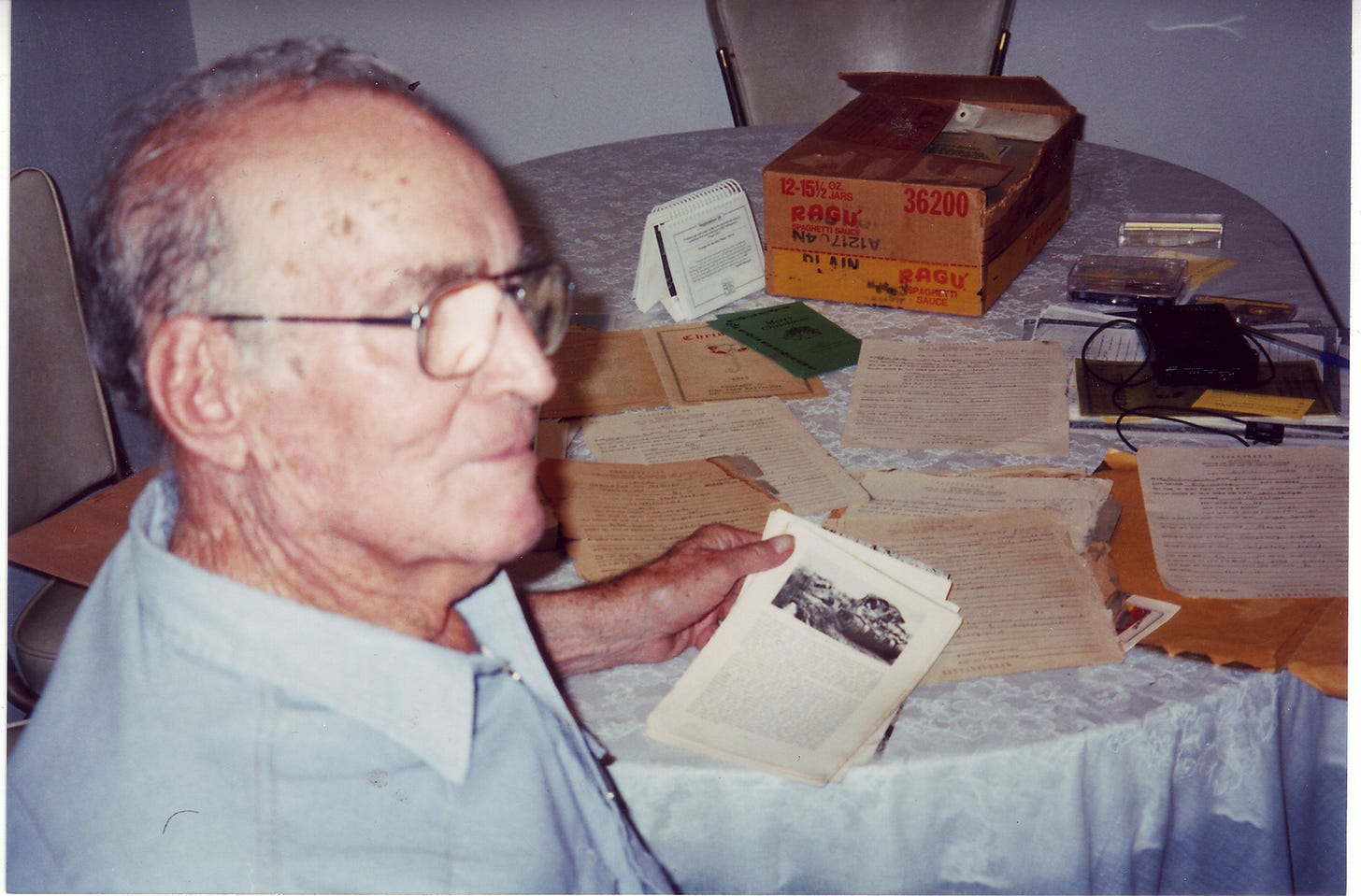

In a recent Substack, “The Spark Plug Thief,” Forrest Dixon, the maintenance officer in the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served, told me how his maintenance sergeant, Frank Mazure, stole a batch of spark plugs which helped keep the tanks from being sidelined when they were needed most. In my 1994 interviewing trip, I visited Jake Driskill at his home in Claude, Texas, because he figured prominently in another story I was researching, about the battle on Hill 122.

After I spoke with Clark Mazure, Frank’s son, a few days ago, I revisited my interview with Driskill.

AE: Now, what would your daily routine be like?

JD: Well, I don't know how, of course I would get up, in time for chow. Sometimes I'd be rarin' for that cup of coffee. But a lot of times our work was at night. We would go up to those tanks at night and work on them at night, to keep us from having to go in broad daylight. I'd say that there, I don't know of anybody that changed more sparkplugs in blackout than I had to. Those air-cooled motors, they would fire them up in the morning, before daylight, because when you first fired one of them up they smoke, they'd fire them up and let them idle, they would idle all day long, and foul up the plugs. And we'd have to go up there and, first we had some extra plugs, like one day we'd go up there and have maybe new plugs to start with, we'd go up and get the plugs, put new ones in, we'd bring them back, then the next day, daylight, we'd clean those plugs up where they'd be ready to go again. But we did lots and lots of that, over there, as long as we had those air-cooled tank motors. After we got those tanks with the Ford motor in it, there wasn't much maintenance on them. Unless they were hit, well boy, they were running loose.

That's the kind of routine. I worked, trying to keep the tanks going. Sometimes they'd have two of them that was messed up, you could take say an oil pressure line off of one and put it on the other one and go with it, so they kind of fussed at me one time for leaving a tank stripped, but by stripping that one tank we had about three or four other tanks that were going. There wasn't all that much wrong with any of them but you could just, like I said, we could get an oil line off of one, put it on one. If one had two somethings wrong with it, why we'd just maybe rob it and make another tank run.

The greatest day, though, we were getting into Czechoslovakia and traveling in a column, I followed the last vehicle in a recovery vehicle or halftrack, and we come to this tank that had rolled over on the side of the field, had a road that was built there and it rolled off. So we went to work and we straightened it up and got it running and brought it back up and were still working on it and old Colonel Kedrovsky, he came by, and of course he was our company commander back in Fort Benning, and he knew everybody by name, and he saw us and he stopped, and said, "Boys, this is it. We've had orders to cease firing." That was real happy, a happy time. Old Colonel Kay or Kedrovsky, I had, he was telling me one time that the 712th Tank Battalion had the best so and so maintenance in the whole such and such army. He didn't say so and so and such and such, he could really cuss, he said we had the best maintenance in the whole U.S. Army. It made us feel good, anyway, whether we did or not.

In my work-in-progress, “Tales of Love, Food, Booze, Jumping Out of Airplanes and Winning World War 2,” a series of curated themed stories from my oral history interviews, I’m going to have a section on the importance of coffee and cigarettes. Here’s a vignette told by Ed Stuever, the maintenance sergeant in Service Company, about a captured Russian who stayed with the battalion’s Service Company to help with some of the hard-labor chores.

“Russky gonna cut you throat”

In Normandy, they liberated a young Russian, he was about 21 years old, and the Germans had him digging foxholes. So when he heard the Americans were coming he hid out, and he waited till we came along, and then they told me to take him with me, he’s a good worker.

I had him with me doing hard work, moving the tracks around. We had him from Normandy until August. When we were in Briey, France, he was walking down the main street over that little bridge, and he saluted a colonel of the MPs in a jeep with a cigarette in his hand, and they hauled him away. We never saw him again.

In all this period, he would always approach me and he’d say “Sergeant, what you do when Russia and America come together?” I says, “Oh, I go home. I can go home tomorrow, I have enough points.”

“No, no. You no go home. Russky gonna cut you throat.” Time and time again he would approach me with this, “Smoky, what you do when America and Russia come together?”

I couldn’t sleep with that guy around. I had a real sharp dagger, and I had an extra pair of boots on the truck; they were all worn and I wanted to exchange them whenever I got a chance, for myself, and he said, “No, I want them.”

I says, “No, you can’t have them.”

He says, “Let me have your knife.” This was still in Normandy. And next day he comes back with a shiny pair of Nazi boots on, and he gave me my bloody knife back. So I could never sleep with him around.