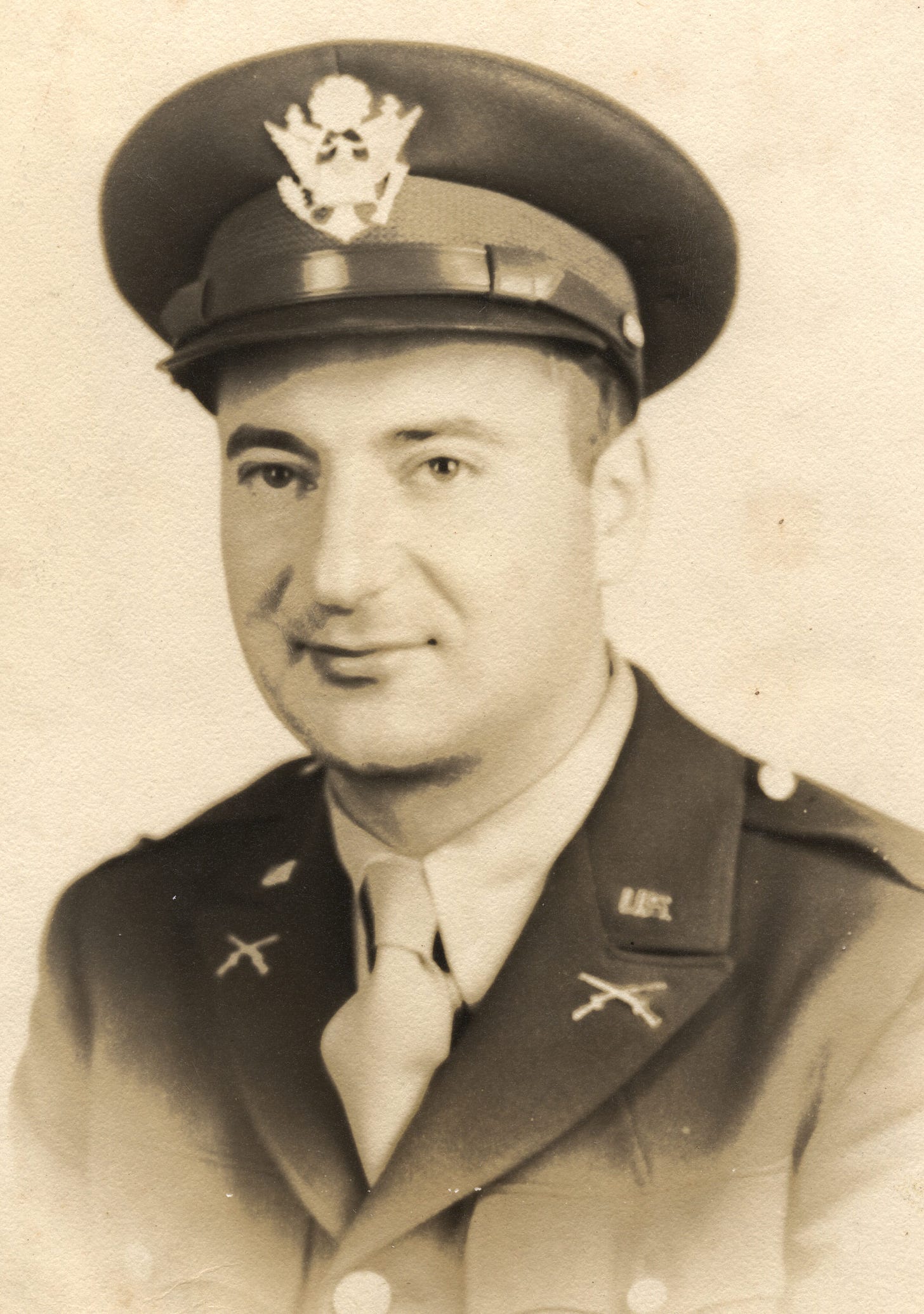

The independent 712th Tank Battalion was but a tiny cog in a mighty wheel, except that for me, it is a lot more than that. I like to say my father was only with the battalion long enough for a cup of coffee and two Purple Hearts, a replacement lieutenant who was wounded within days of joining the battalion in Normandy and wounded again within days of returning in December.

Unlike many World War 2 veterans, Maurice Elson wasn’t hesitant to talk about the war. I didn’t recognize the signs of post-traumatic stress disorder until after he passed away, when I was 30 years old. I used to tell the story of how when I was about four years old I woke him from a deep sleep and he tossed me halfway across the room. Each time I would tell that story he would throw me a little farther, so I figured I’d better stop telling it before I bounced off the wall.

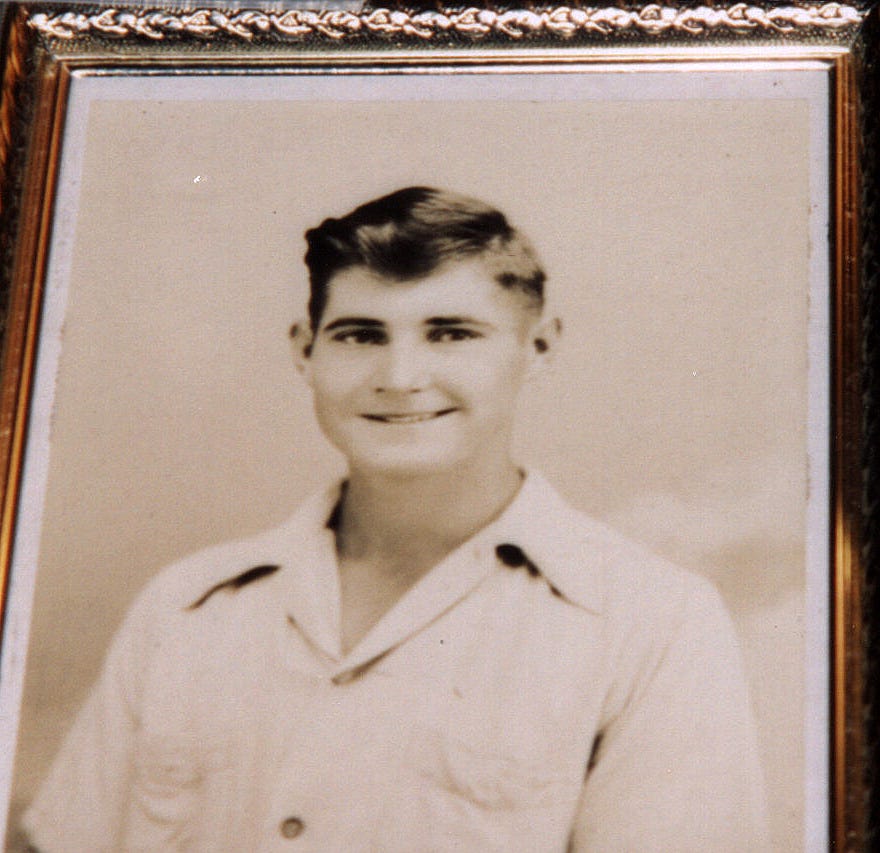

As I grew into my teens, my father and I were not very close. He never took me to a baseball game. He did take me to a Cub Scout meeting. He once said he would have liked to have had a beer with my maternal grandfather, who was a doctor in World War 2 and was a much better eye, ear, nose and throat doctor than he was a grandfather, but he never did. I don’t think my father knew or remembered his own grandfather because his parents brought him and his three older siblings to America from Russia when he was five years old. I wish it had occurred to me to have a beer with my father before he died in 1980. Although when I was eight or nine and there was some sort of gathering at our summer home in New Rochelle, New York, the adults were drinking beer and I didn’t know that there was a difference between root beer and beer, so I insisted that they give me a glass, they did, and I spit the damn stuff out, but I can’t say that qualifies as having a beer with my dad.

My mother wanted me to be a doctor, hoping I might one day inherit my grandfather’s practice, but when I was a freshman in college I joined the campus newspaper and between that and a part time job at the New York Post I could barely stay awake in class. By the time I graduated from the City College of New York I was working full time as a copy editor at the Post. My father had had a couple of heart attacks and moved in with my older sister in Massachusetts, and before I knew it I was in my late twenties and he was having a quadruple bypass. I was working a lot of overtime, as well as nights and weekends, in the sports department of the Post and I didn’t see him often. Then he had another heart attack and I thought I would buy a little tape recorder (a Sony Recording Walkman) and get him to tell his stories about the war when I went to visit.

I forgot to bring the tape recorder, and would never get another chance.

Seven years later, I found a newsletter from the 712th Tank Battalion. It had things like who had a new grandchild, who was retiring, who hadn’t paid their dues, who paid their dues but didn’t include a note about what was going on in their life, and then there were a few grainy black and white photos of young men standing in front of tanks parked in front of damaged buildings. As I read the newsletter, I realized I remembered only a few details from the stories my dad had told.

I remembered one name, Ed Forrest, who was a fellow lieutenant he must have bonded with in those few days of combat. He said something about Ed gave him the impression Ed might not want or expect to return home. He said Ed volunteered to go on a “suicide” mission and that he didn’t know if he would have volunteered for something like that, although Ed did return. He said he thought Ed’s father might have been a minister and that he might not have approved of Ed going off to war. And I remembered the name of a place where he was wounded the second time, a city in Germany called Dillingen. He was retired with a 90 percent disability from the Army and could travel “space available” on military flights, and one year he even visited Dillingen, although I never pressed him for details about the battle.

And I remembered he said the first time he was wounded was because after training for three years, when he finally got into a battle he wanted to see what was going on, so he stuck his head up.

This was all I remembered when I wrote to the newsletter. I asked if they could put a note in asking anyone who remembered Lieutenant Elson to get in touch with me. A week later I got a letter from Sam MacFarland saying he didn’t know my father but the battalion was having a reunion in a couple of weeks; if I came he would take me around and see what we could find.

I went, and found Charlie Vinson, who was a sergeant in headquarters who processed my father when he reported to the battalion in late July. I found Ellsworth Howard, the battalion executive officer who delivered my father to the platoon he was to lead, but he couldn’t remember much more. (At full strength the battalion had 765 men and about 500 replacements joined its ranks.) And then I struck paydirt. I was introduced to Jule Braatz, who was the platoon sergeant of the platoon my dad was supposed to lead as the replacement for the first lieutenant killed in combat.

That lieutenant was George Tarr of West Newton, Pennsylvania. He was killed on the battalion’s first day in combat, July 3, 1944. I thought at the time my dad arrived shortly after that, but it was actually almost three weeks. Braatz said my father told him he was an infantry officer and knew almost nothing about tanks, except that his records showed he attended a tank demonstration. Braatz said my dad told him to keep leading the platoon until he knew more about what he was supposed to do.

That was like my dad, I thought, doing the right thing, delegating the responsibility for leading the platoon of five tanks and five crews until he was more comfortable in that role.

Braatz gave my father a tour of the Sherman tank, and told him to be careful getting off as the deck was two stories high, and that my father jumped off, struck his foot on a rock, twisted his ankle and had to go to an aid station. While he was there, the platoon was sent on a mission without him.

The rest of the story, Braatz said, was hearsay, or thirdhand information, because it was told to him by a tank driver named Pine Valley Bynum, who later was killed. While Braatz’s platoon was at the front, Pine Valley’s platoon was sent to the same area. He didn’t have an assistant driver, so my dad hitched a ride in order to join up with his platoon. When the platoon was ordered to stop, Braatz said Pine Valley told him, my dad said he wanted to get out and look for his platoon. Braatz said Pine Valley told him he should stay in the tank because the area was under enemy artillery fire, but my dad insisted on getting out. He was wounded within minutes. (Ironically, I would learn much later, when Quentin “Pine Valley” Bynum was killed on January 14, 1945, at Bras, Luxembourg, his lieutenant at the time, Wallace Lippincott, ordered the crew to abandon tank and Bynum pleaded with him to stay inside because the shell that just struck the tank was high-explosive and not armor-piercing, but the lieutenant insisted and he, Bynum and a third crew member, Frank Shagonabe, were killed outside the tank when a second shell exploded.)

Getting back to that July incident, what Braatz said likely was the source of my father saying he wanted to see what it was like being in a battle. Among the injuries he received, a piece of shrapnel penetrated his helmet but was kept from penetrating his skull by some tissue paper wadded inside. When I mentioned this to Charlie Vinson, the first veteran who remembered him, Charlie said with some authority that that wasn’t tissue paper; it was his socks. “You mean my father wore his socks on his head?” I asked. He said that because of the frequent rain and mud the battalion encountered, the tankers would suffer a condition he called “tanker’s toe,” which I assumed was akin to trench foot. It was important to change socks often, and where, he asked rhetorically, was the best place to keep a pair of socks dry? In your helmet, he said.

I didn’t say anything, but I dismissed that likelihood because of the short time he was actually with the battalion, which was on the front lines for most of its 11 months in combat.

By now I knew the name of the lieutenant my father replaced, George Tarr, and the circumstances of his first wound (I would, again much later, learn that it took place on Jul 28, 1944, during the battle for Seves Island near Periers, France). I also learned that many of the veterans remembered Ed Forrest, who was an original officer of the battalion and was killed late in the war, although none seemed to have gotten the impression my father shared that Ed might not have expected or might not have even wanted to make it home. And then there was Dillingen. “Ohhhh, Dillingen!!!” was the almost universal response I got when I asked about it.

This was because the battle for Dillingen, an industrial city on the east side of the Saar River, involved the entire tank battalion; and also, because after crossing the Saar and engaging in a fierce fight, the battalion had to abandon its gains and retreat back across the Saar in order to go north and join in the Battle of the Bulge. Once again, my father was not wounded in a tank but rather was leading a patrol in the middle of the night carrying supplies to the front and evacuating wounded from a captured pillbox.

I was not the only “next-gen” at the reunion. Wanda O’Kelley, who was 2 years old when her father, Richard Howell, was killed, was there with her mother, Lillian Howell, who never remarried; and twin sisters Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten, who were 16 years old when their 18-year-old brother Billy Wolfe was killed, were there as well, to meet Billy’s lieutenant, Francis “Snuffy” Fuller.

I had learned a great deal about my father’s experiences, but the journalist in me wanted to know more about these other stories — the tragic deaths of Pine Valley Bynum, Billy Wolfe and George Tarr; the battle for Dillingen; and more about a few stories I overheard the veterans telling in the hospitality room, the parking lot, the hotel lobby. I had brought the Recording Walkman I never got to use with my father, but I only recorded my brief interview with Jule Braatz. Interestingly, when a few years later I transcribed that interview, I remembered it being about 15 minutes long. In actuality, it was 45 minutes long.

Thus began a journey that has lasted through hundreds of hours of interviews and conversations with men and women of the Greatest Generation and resulted in the creation of one of the first web sites with significant World War 2 content, the writing of numerous books, the production of multiple oral history audiobooks; blogs, library programs, source material for several documentaries and popular books about the war, and now a Substack.

Aaron, thank you for the opportunity to respond. I like you are a son of a 712th veteran. My father Phillip C. Morgan was wounded on July 3, 1944 in the fight near Pont Auny. He went on to survive the war and was reassigned from the hospital to the 1/66 Armor for the rest of the war. He stayed in the Army and retired in 1971 as a CSM with Korea and Vietnam under his belt. Unfortunately, he passed in 1974. I also became a career man in part to honor his legacy. I would love to further the conversation if you ever get the chance.

David Morgan, Colonel US Army Retired

Love this personal story! It's what makes WWII oral history so great! I never recored my father. A medic, landed at Normandy after D-Day. surgen at Bulge hospials. I was 16 when he passed.