Valorous action became so commonplace that we all knew that three things were necessary for an award for bravery. 1) the opportunity to do something beyond the normal call of duty, 2) somebody to see you do it and report your actions, 3) somebody at headquarters who could "write it up." Sadly, the third thing was not always available. Often the second thing was lost when witnesses became casualties. — Lester O’Riley, executive officer, 712th Tank Battalion

The painting above depicts the Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944, a donnybrook between 35 B-24 Liberators and more than 100 German fighter planes. You tell me nobody in any of the 25 bombers that were shot down, the four that crash-landed, the two that returned to an emergency landing field on a wing and a prayer, and the four that made it back to their home base, all with an average of ten-man crews, there was nobody whose acts of courage and heroism and sacrifice deserved a Medal of Honor, or even a Distinguished Service Cross?

In 2000 I sat down with George Collar and Bill Dewey, the founders of the Kassel Mission Memorial Association (which later morphed into the next-generation Kassel Mission Historical Society), along with Doug Collar, George’s son, and we discussed what George and Bill would like to see go into a book about the mission. Sadly, both men passed away before the spate of books about the mission, including my own Up Above the Clouds to Die, were published. But Bill Dewey said he envisioned a book along the lines of “Black Sunday,” a book about the Ploesti Mission.

According to the National Medal of Honor Museum, five Medals of Honor were awarded to participants on the Ploesti mission, not to mention more than 50 Distinguished Service Crosses, more than 40 Silver Stars and every flyer on the mission was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Every one of those decorations was deserved.

Two of the three factors mentioned in Les O’Riley’s quote appear to have played into the lack of recognition for the many acts of heroism on the Kassel Mission. While there were plenty of people in headquarters who knew how to craft the language required to “write it up,” there was a disincentive to do so: The battle was the result of a mistake, and recognizing the heroism of its flyers would impede the effort to hide the magnitude of the disaster and might hurt morale. To the best of my knowledge, few or no medals were issued for two other World War 2 disasters: Exercise Tiger, the tragic practice landing for D-Day that saw two fully loaded landing ships torpedoed and sunk in the English Channel; and the sinking of the Indianapolis, which was torpedoed after delivering the atomic bomb to the island of Tinian.

I mentioned in my last Substack that I believed Stanley Krivik, a pilot on the Kassel Mission, deserved the Medal of Honor, but there were others as well. How many pilots died keeping their planes flying until some or all of their crew had time to bail out? I don’t know his name but I heard of one waist gunner who stayed at his station while his fellow crew members bailed out and the B-24 turned downward and plummeted to earth with him still firing.

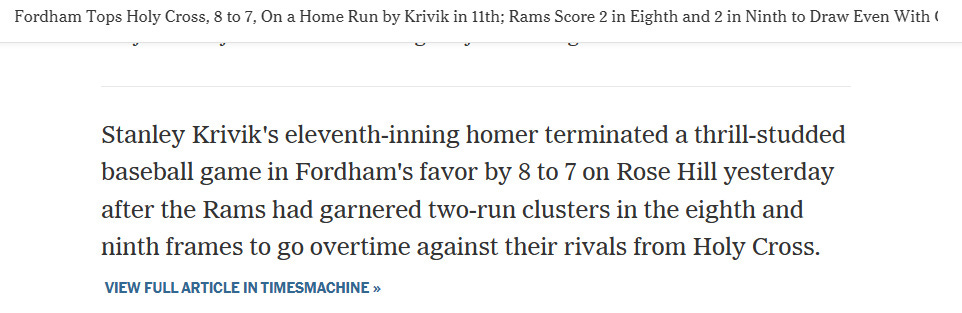

Stanley Krivik was a hero before World War 2, although heroism on a football or baseball field is a different sort of heroism, but it might foreshadow the blend of confidence and courage needed to make what could be life or death decisions.

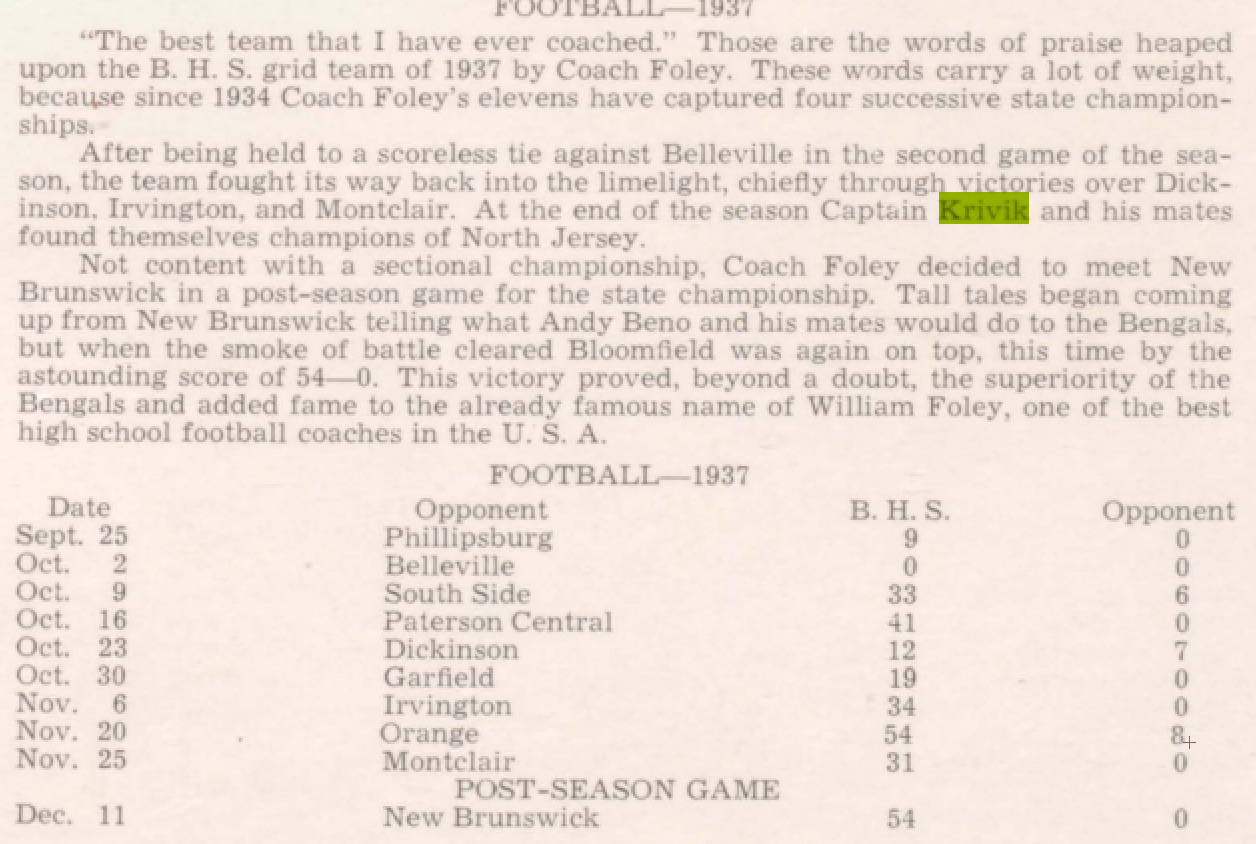

At Bloomfield, New Jersey, High School, Krivik was the captain of what might have been one of the most dominant football teams in New Jersey history. Holy cow! Look at those scores by the 1937 state championship team.

Krivik played football and baseball at Fordham University in 1940 and ’41, was a place kicker at Notre Dame after the war, and was “the strongest person I knew,” said John Cadden, a B-24 radio operator whose life Krivik saved on the Kassel Mission.

I never interviewed Krivik, who served in World War 2, Korea and Vietnam and died in 1970, but it was my interview with Cadden that provided a glimpse into his character.

John Cadden: Shortly before the Kassel mission they captured Brussels with the runways intact, so if anybody had mechanical problems or battle damage, instead of heading for Switzerland or Sweden, we were told to try to make it to Brussels because the runways are intact and the American forces are in control. That’s influential in the story of our crew because after the battle damage we were all set to bail out. We knew we couldn’t get back to England, so we headed for Brussels.

After we dropped our bombs, my first indication that we were being hit by fighters was from the waist gunners on the intercom, and you could feel the bullets whizzing through the fuselage. They both reported the Focke-Wulf 190s attacking, and our tail gunner, Henry Puto, was hit right from the very start and knocked out of his turret. He had wounds to his face and to his legs. We didn’t know, we just knew he was wounded at that time.

We had lost one engine, and Krivik, the pilot, managed to get it feathered, but we had no oil pressure in another engine. So he alerted me to go down and open the bomb bay doors. He didn’t say we’re going to bail out but I knew that’s the reason he wanted to open the bomb bay doors. So I went down, and I was about halfway through opening the bomb bay doors when bullets started to whiz around the bomb bay. And that’s the last I remembered. I don’t know how long I was out. I got knocked out. Because I woke up by the nose wheel, which is further away from where I should have been. I was off my oxygen tank. I had the portable oxygen tank with me. I was off that, and I’d lost my helmet and my head was buzzing.

I didn’t know what was going on. I gathered my senses. The first thing I went for was the bottle of oxygen, and I got back on the oxygen. Then I started to look around for my helmet. I went to pick up my helmet, and it had been hit. It’s a steel helmet with the hinges on either side for the earflaps because of the earphones we wore, and it apparently hit just about where the hinge was and took the hinge off and made a big crease right through the helmet. And that explained why my head was buzzing.

I felt and it wasn’t bleeding. So then I went back to opening the bomb bay doors. They were half-open at that point. The firing had ended by that time, and there was no power. We’d lost all of our hydraulic fluid. So I cranked them open manually, and I got them open. I went back up to the pilot and told him I had the bomb bay doors open. And he was in conference with the navigator at that time, his name was [Dan] Dale. And they were deciding where to go and what to do. And they thought that at the rate we were losing altitude we could make Brussels, so he told me to go back down and close the bomb bay doors, and get the wounded up on the flight deck where they’d be warm. Because by that time the tail gunner and the two waist gunners were wounded.

I should mention that when I first came up on the flight deck to report to Krivik that I had the bomb bay doors open, he looked like he saw a ghost. His eyes opened wide, his jaw dropped. And about a week later in the hospital Krivik came over to see me; he was in the same hospital. I said, “You had the funniest look on your face.”

He said, “You were covered with hydraulic fluid, and I thought it was blood. I couldn’t imagine somebody losing that much blood.” So that’s the humorous part.

So I went back down and closed the bomb bay doors, and we flew almost an hour I guess, but gradually losing altitude, and we were heading towards Brussels. And when we thought we were close enough, we thought we’d drop down below the ceiling and look and see on the ground, you could pick up rivers or something like that. And when we came through the overcast, there was nothing below us but water. We were about, I’d say 2,000 feet, no higher, and nothing below us but water. Everybody was surprised at that point.

In the meantime, as the radio operator I was the medical fellow on board. Paul, one waist gunner, was wounded but he was able to treat himself. The same thing with Bill Rand, the other waist gunner. Puto was in a lot more pain. I gave him a shot of morphine and it quieted him down.

Dale and Krivik had a hasty conference. They assumed we were over the North Sea, which was a correct assumption, and if we just keep heading west we’d hit England. Which we did. But in the meantime, we stripped the plane of anything that could be stripped out of it and dumped in the ocean.

When we got down around 1,200 or 1,000 feet, not much higher, we came over England. And Krivik immediately knew where we were, and headed for the air base, with his course set on the runway. Of course, at the sight of land everybody cheered up, you know, we were very happy then. And I guess Krivik thought he could get it down on the runway. We didn’t have any hydraulic fluid or brakes or anything so we’d probably run off the end of the runway but that was better than bailing out. We didn’t have much altitude left, 800 or 1,000 feet.

So the big thing then was to get the wheels cranked down, and we had no problem with the main landing gear. It came down and locked in place. But we couldn’t get the nose wheel locked in place.

At that time, everybody that didn’t belong on the flight deck went back to the waist to get ready for a crash landing, including the navigator. The radio operator and the engineer stayed up with the pilot and co-pilot. We all had positions we’d take to brace ourselves for the crash. Mine was behind the co-pilot.

I don’t think we were much more than 500 feet off the runway when Bugalecki finally got the nose wheel locked and he came up, and I thought – everybody thought, I guess, now that we were going to come in and he was down there playing with it, he was liable to be down there when we landed and he’d get crushed.

I would say we didn’t have much more than 500 feet when he finally got up out of there and let the pilot know that they were locked in place.

So we felt pretty good. Braced for the crash. We knew it would crash. And, next – there’s a little window by the radio set, when you’re back behind the co-pilot on the left hand side of the fuselage is a window down by your knee and I was looking at whatever scenery you could see going by, and all I could see were trees. I never noticed trees on our approaches before to the runway. But all I could see was trees.

The next thing I knew, Krivik was pulling me out of the wreckage.

When we were both in the hospital, he came over to see how I was doing. He said when he got down to the runway, he could see it was covered with lorries and British wreckers. He didn’t say how many. He said “lorries,” though, not just one; it was several. And he said he didn’t want to kill everybody on the runway so he just had to overshoot it. He couldn’t get back up and go around. He had to keep going, and he just overshot the runway and crashed.

I remember seeing the trees, but I don’t remember anything beyond that. The next thing I knew I was in the wreckage; I could see the sky, but there was stuff all on top of me, on my legs. Everything was on fire. I don’t think we had much gas but there had to be some gas, and there’s still .50-caliber bullets because I’d thought we threw them all out but they were going off all over the place, from the heat. Plus I was in a fur-lined suits I think I would have had a lot of severe burns, and I was hot. But it protected me from being burned. I didn’t inhale any fumes or anything because it was wide open, I was looking at the sky.

I was conscious at that time, and I heard Krivik pulling Trotta out. I think he took him out seat and all. Krivik was probably the strongest person I ever saw. He was a bull. Matter of fact, I don’t think many pilots could have kept that plane in the air, because he had no hydraulic fluid, and you had to be pretty strong to handle that without hydraulic fluid, and he flew it all the way back that way.

He pulled out Trotta, and then I heard somebody yelling that “Cadden and [Donald] Bugalecki are still in there,” so he came back in and grabbed me and yanked me out and got me away from the plane. And I took about two steps and fell. And then he went back for Bugalecki. He pulled Bugalecki out. So I was very happy I was flying with Krivik that day.

Aaron Elson: And who pulled the gunners out?

John Cadden: They just landed up all over the field. I guess what happened is, the waist gunners and the tail gunner and the navigator and the nose turret gunner, they set up a net in back of the fuselage, across the fuselage, and they lean into that so when the crash comes they’re braced by the net, they won’t go flying up into the wreckage. And I guess everybody but Dale took advantage of that during the crash. He just acted as though it was going to be a normal landing, and he just sat down on the floor of the plane, and I guess when the plane crashed it broke in the middle and they all flew clear of the plane. Ended up scattered on the field with no injuries, really. But he ended up going into the bomb bay, and he got killed.

I doubt that many of the flyers who performed heroically would consider themselves heroes; they were doing their job, trying to keep themselves and their buddies alive, and some would have been, as Les O’Riley of my father’s tank battalion said, embarrassed because they might have felt that others deserved a medal more than they did. Nevertheless, students at Bloomfield High School likely have no idea about who Stanley Krivik was, whereas if he’d received recognition in the form of a Distinguished Service Cross or Medal of Honor, there probably would be a plaque acknowledging his heroism in the trophy case, inspiring the students of today.

PS: The old newspaper guy in me just re-read the blurb in the Times about Stanley Krivik’s game-winning home run. What colorful language sportswriters used back then. “terminated a thrill-studded baseball game” … “garnered two-run clusters”. Which reminds me of a headline written by Lester Rose at the New York Daily News shortly after I started working there in 1978. The Milwaukee Braves had defeated the Yankees, and Lester’s back page headline, in large type, capital letters, read: MILWAUKEE WISCS YANKS.

PPS: My complete interview with John Cadden is available in booklet form and for Kindle at Amazon.

I was good friend of John Billings, who flew Polesti. He flew from1938 till 2022, they say a near reacord of flying time. Also flew OSS missions, including the famous Operation Greenup with OSS agent Fred Meyer. The script writer for the movie "The Inglorious Bastards" got some ideas from that mission. See the documentary "The Real Inglorious Bastards"