Pistol Paul, the Streets of New York, and Freelove Cary

Maybe the "good old days" weren't all that good

1996, what was that, nearly 30 years ago? Back then, and beginning a decade earlier, when I went to reunions of the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served, and sat and talked with, sometimes interviewed, the World War 2 veterans and sometimes their spouses or companions, I had the feeling that I was immersed in history. It was history of the war, naturally, but it was also history of the times, the Great Depression, history of the era before many of the spectacular advances in medicine from which later generations have benefited, history of family dynamics that have changed over the years.

While looking through this transcript of a sometimes rambling tape from the 1996 mini-reunion in Bradenton, Florida, which provided some of the material for my last Substack, I came across a fascinating conversation between Ruby Goldstein, a tank commander in A Company, and Jim Cary, the B Company commanding officer, both of whom I have written about before. Both Ruby and Jim were wounded, Ruby once and Jim twice, but this excerpt is more about other stuff.

Ruby was one of the battalion’s great storytellers, and Jim, who was a journalist after the war, was one of its more eloquent members. I had asked him what he remembered about Marshall Warfield, a lieutenant who was killed in September of 1944. I would eventually interview Warfield’s widow, Olga, who was quite a character in her own right.

Jim Cary: Well, this was one incident, I can’t even remember when it took place; it might have been in England, or it might have been in that period after we landed in France but hadn’t gone into action. We were both saying we just couldn’t quite believe or understand that we could be killed in action. That ability to grasp the concept — you knew it was there, but mentally you couldn’t come to any, he said something to the effect, “Yeah, I know it’s not gonna happen to me.” And as I understand it, after he was shot, he knew he was dying, and said something to the effect, “I’m not gonna make it,” or something like that, so I immediately thought of our conversation.

The other thing I can remember was about his wife. She was a very bold woman. When we were still part of the 10th Armored Division they called the commanding officer, General Newgarden, they called him Pistol Paul. And the Newgardens were having a reception one day, this would have had to be back in Benning, and she was going through the line. She came to Mrs. Newgarden, they shook hands, and she says “How’s Pistol Paul?” I don’t know what the reaction was but I can well imagine.

Those people that were in recon units, of course, were running a much higher level of being wounded or killed than most other people in combat. By the time we got up there, of course, your chances [of survival] had increased considerably, but they were out there from the beginning. It’s just, the goddamn thing about it is this: It’s plain damn luck whether you made it or you didn’t make it. I mean, you can’t come to any other conclusion. And it bothers the hell out of me sometimes. I think I told you when I took that task force out and we laid down a bridge over the last antitank ditch before we closed up to the Saar, we got all kinds of praise, see, for getting that accomplished. Nothing happened to us. We went out, it went smoothly, we got the bridge down, we got a platoon across. Over on the left, there was an infantry patrol went out and they got the hell shot out of them. And they didn’t get a damn thing. That was just another patrol. If I hadn’t moved about one or two seconds before I did up in the Bulge, instead of getting hit in the leg I’d have been hit right in the chest.

Ruby Goldstein: Sometimes a thing happens out of proportion and you don’t even realize it. A fellow goes through all kinds of things, could have been killed dozens of times, no wounds, no nothing, comes back home, car hits him and he gets killed. An automobile accident, walking on the sidewalk, he crosses the street, bingo, that’s it.

Jim Cary: I know the feeling.

Ruby Goldstein: It happened many a time. You read about it when somebody, not now but I mean years ago, that had been over there and nothing, didn't get a scratch, comes home, gets killed.

Jim Cary: I know the feeling because I arrived back in the States on a hospital ship. I was ambulatory, I think it was April the 10th of 1945 and April 11th I went into New York, and that's the day that Roosevelt died. I remember it so well because there were people standing around shoeshine stands and listening to the radio reports and so forth. I never knew New Yorkers to weep before that; I thought they always spit. But anyway, they're soft-hearted like the rest of us. But the point I was gonna make was man, I come to a stop sign and the New Yorkers pay absolutely no attention to it, they keep walking if they can get across. I obeyed every single traffic signal. I wasn’t gonna get knocked off by one of those cabs after getting back from the war.

Ruby Goldstein: When you came back, did you get in New York?

Jim Cary: Fort Dix, I think it was.

Ruby Goldstein: I went to Halloran General Hospital in Staten Island; that’s where we landed.

Jim Cary: Seems to me it was Fort Dix. It didn’t take us very long to get into New Yorki. Fort Dix would be not very far from Staten Island. I had a very bad guilty conscience later for what happened on that day. We were gonna go into New York. We all had, I think it was three free phone calls, and I called Norma first, went back and got in line, called my mother, went back in line, I was gonna call my older brother who I was very close to. Guys came over, “Come on, we’re going, the bus is leaving,” and I thought, well, hell, I didn’t want to miss that bus, and so I left. His wife told me afterwards he sat by that phone waiting, oh god, to this day I haven’t gotten over it. I should have forgotten about the bus. He practically, he was a substitute father to me. He made me study, god I hated it when he did.

Aaron Elson: What happened to your father?

Jim Cary: My father died when I was seven. He had typhoid fever and what they called kidney complications. I don’t know what that meant. I came from a very athletic family. My father was Border States veterans tennis champion, and my older brother I was telling you about, he was first Border States boys champion, then junior champion, and anyway, Dad went out to defend, he was feeling badly, he thought he had the flu or something. He went out to play in the finals and defend his championship and he lost, came home and went to bed, typhoid fever. And in those days they had nothing to fight it with, so that was 1926.

Ruby Goldstein: My father passed away in 1925. I was seven years old at the time.

Jim Cary: We’re exactly the same age. Then you were born in 19 …

Ruby Goldstein: Seventeen.

Jim Cary: Seventeen?

Ruby Goldstein: December 28, 1917.

Jim Cary: Well, then you would have been nine, not seven.

Ruby Goldstein: No, I think I was seven at the time when he died.

Jim Cary: See, I was born in October of1919.

Aaron Elson: When you say he was a veterans champion, had he been in World War I?

Jim Cary: No, I don’t know where he was in World War I. Now that you mention it, I think he was still in a training camp or something, but I’m not too sure about that part of his history. I know he had a lot of German artifacts. He had German helmets and gas masks and I used to parade around the neighborhood when I was a kid wearing those things. All the kids would cozy up to me wanting to wear one of those helmets. Kids are funny.

Aaron Elson: So maybe he was in World War I.

Jim Cary: I guess he was in the service. I don’t think he got overseas, though. I don’t know how he got ahold of that equipment. He was a dentist. He went to the University of Pittsburgh. He was from Binghamton, New York, and he went to dental college at the University of Pittsburgh. This would have been approximately 1909, and he wanted to practice in California. He got out at midterm, and so he got on the Southern Pacific Railroad, which came down through Texas, and went along the border and then across into California. In those days it came right down along the border of Arizona. It stops — they always stopped at every place — he got off the train, it was January or February, there was this brand new little smelting town there called Douglas, Arizona, right on the Mexican border, and he had never seen winter weather like that. The sun was shining and this brand new town all laid out, and so he went and got his suitcase. He couldn’t practice in Arizona because he hadn’t passed the territorial board, and so he went across the Mexican border and set up a chair in this little border town, and operated from a pedal type drill.

Ruby Goldstein: Like the old barber chairs.

Jim Cary: Yeah. Until he could take the board, so he was one of the first dentists in the territory there.

Aaron Elson: How did your dad pass away?

Ruby Goldstein: He was operated on in Lynn Hospital, and at that time, what did the doctors know, compared to today? When they cut him open, he must have had stomach cancer, that was it. He didn’t last too long, either. When I was operated on here, I also had cancer of the colon. But they cut it out, resected it. I’m here.

Jim Cary: You know, we don’t realize what killers some of these diseases were. So many people died of consumption, tuberculosis, from peritonitis or burst appendix. Typhoid is no problem today; they just give them some antibiotics and it knocks it out. In those days, they had caught the typhoid they’re almost positive from drinking unpasteurized milk. Milk in those days was not pasteurized. I think there was one dairy in Douglas that had pasteurized milk and everybody sort of thought this was hilarious that anybody would drink milk that had been boiled. We didn’t realize it wasn’t boiled but that’s what the general concept was. But that’s what killed him. He probably got it from the milk.

Ruby Goldstein: We used to get our milk fresh from the farm.

Jim Cary: Yeah. We thought that’s the way it was supposed to be.

(How timely is this discussion of the perils of raw milk in light of recent news?)

Ruby Goldstein: We didn’t have the money to buy food or milk or anything. So my younger brother and I used to go down to this farm, this woman, she gave us the eggs, milk, all for nothing.

Jim Cary: They talk about the good old days. They weren’t so good. There were some things that were awful rough. Most families were large families, had seven, eight, nine, ten children, and if you could raise half of them to maturity you were lucky.

Ruby Goldstein: We were five boys.

Jim Cary: Did they all make it?

Ruby Goldstein: No, my oldest brother’s gone. My second oldest is gone. And there’s three of us left. My youngest brother and one older than I.

Jim Cary: I think my father’s death and the Depression affected my life, branded it more than anything that ever happened to me. People who lived through the Depression, you didn’t forget it.

Aaron Elson: He passed away in 1925?

Jim Cary: In ‘26. He was still a young man; he was about 44 or 45, and he hadn’t really made any preparations for; he didn’t have much life insurance. We did own three pieces of property there in Douglas, but by ‘29 they were pretty well dissipated. My mother had never worked. She had to go to night school and work. I remember she made $90 a month, and our food budget was $30 a month. We ate an awful lot of beans, I want you to know. But so did everybody else.

Aaron Elson: How much older than you was your brother?

Jim Cary: Ten years. I have two older brothers and an older sister. Doug was ten years older; the other, who’s still alive, was nine years older, and Ruth was three years older.

Ruby Goldstein: When we had to get bread we never bought bread that was made that day. We bought old bread because it was much less.

Jim Cary: Oh yeah.

Ruby Goldstein: We hardly had any money. This is when if you wanted hot water, you had to put a quarter in the meter downstairs to heat the tank to get the hot water. So my mother would take coal and burn it in the stove, and where do you get coal? Well, you’d buy it. I didn’t steal it. When the coal trucks came out of the freight yard, they’d weigh them before, empty, then when they load up with coal they come back on the scale and weigh them again loaded, and they deduct the difference. When they’d come down, the streets were not paved like this, it was cobblestone, so we used to throw rocks up on the coal truck, and whatever coal came off we’d pick up, then throw in boxes and bags and run like hell. Same thing with ice. The ice man would go and get a chunk of ice and bring it up to the house. We’d be outside there knocking the ice off and running like hell.

Jim Cary: When I came back from Japan with the AP [Associated Press] and was sent to the Washington Bureau, I became aware rather quickly that Cary — my last name is spelled Cary, no e — that Cary was a big name in Virginia. I couldn’t figure out why, because I didn’t know of any relatives in Virginia. So I went to the genealogy section of the Library of Congress, and it turned out they had four books on the Cary family there. And I went through it awfully fast, so I was just getting the highlights. There were three guys that came over in the late 17th century, in the 1600s, and one settled in New York and one in Boston and one in Virginia. And the Virginia branch of the family became pretty prominent; sort of the patriarch of the clan was a guy named Colonel Miles Cary, and he must have been one of these hard-headed bold type people, I can almost see, because one of my brothers is almost like that.

Anyway, he was a pretty tough character I guess. I found traces of the family, for instance, if you go to the Arlington cemetery and stand in front of the Lee mansion, and then turn down the path to the left the first grave you come to was the first woman buried on those grounds, long before it was a national cemetery, and her maiden name was Cary. And I found out that the wife of Lord Fairfax, who was one of George Washington’s best friends, was named Sally Cary, or Sara Cary; they called her both. And Washington had a very definite crush on her, and he carried on a voluminous correspondence with her; they even made a movie about it, a television movie, and that was one of his secret loves. There's also a man named Cary buried in Westminster Abbey; I've forgotten his first name.

Then I found in one of the books in the Library of Congress my paternal grandfather’s name. This particular book was not textual; it had the various families outlined, who the parents were and who the children’s names were, what the parents did. It was just sort of a diagram of each family. I kept going, turning back till I came to Andrew Shaw Cary’s name. He was in this family. That was about 1840 or something, that period, when he was born. And one of the kids, the last name of one of these families was Freelove. Can you imagine naming your kid Freelove?

Aaron Elson: His first name?

Jim Cary: Yes, his first name was Freelove. Norma was the one that found that, and of course we both collapsed when we saw it, and the only thing we could figure out was, by the time this kid came along the father must have been pretty old; maybe he was pretty suspicious of where that kid came from. There were a lot of ministers in our background for some reason, I can't figure out why.

Aaron Elson: How about in the Civil War? Did you have ancestors in the Civil War?

Jim Cary: Well, I might have. I don’t know. A number of years ago Clegg Caffery had a bunch of us down to a mini-reunion in New Orleans, in Franklin, Louisiana, where he lives. We took a motor coach trip around to a lot of the various old Southern homes there and one place, there is a Cary plantation down there. On one trip we were in England going around the countryside; we came to a sign and it said “Castle Cary.” I said “Stop the bus! I want to go claim my inheritance!” They stopped the bus long enough to let me take a photo, but that was all. From here on I want to be known as Sir Jim. Somehow that didn’t take.

Aaron Elson: What was the boat ride like going across the Atlantic on the Exchequer.

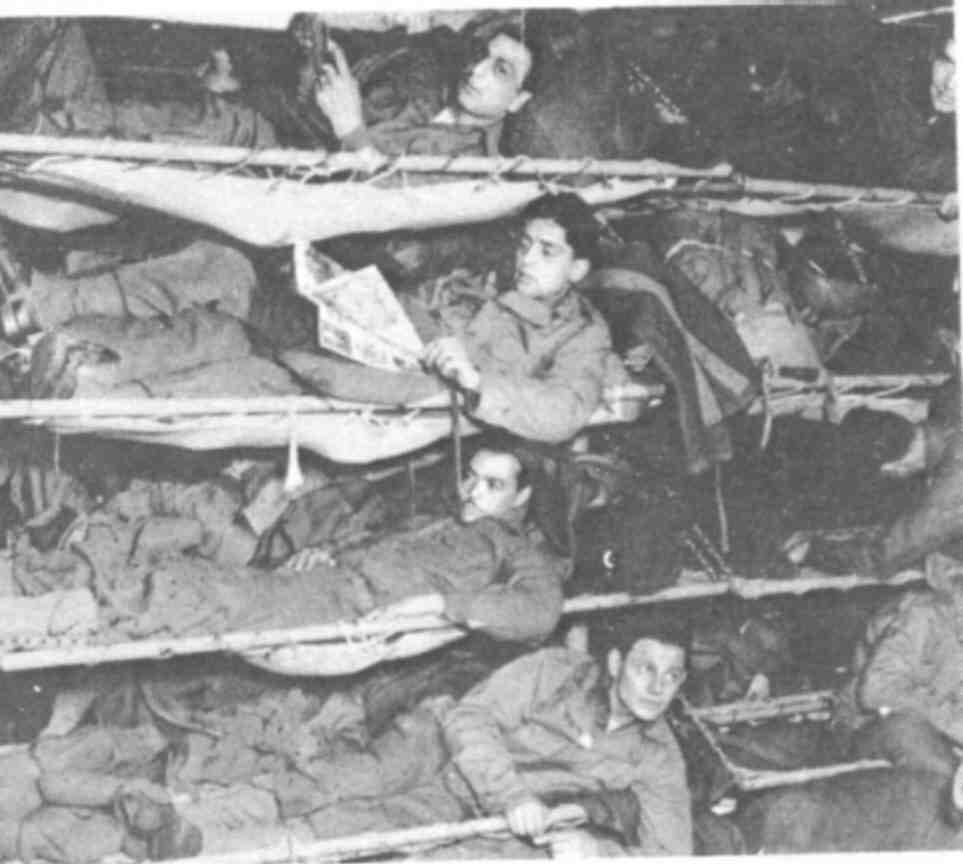

Jim Cary: It was a lot worse on the enlisted men than it was on the officers. In fact, I think it was pretty rough on them.

Ruby Goldstein: You left from, where we left from, right, Boston? From the Army base. That’s from the Army base in Boston we left, when we went from Myles Standish in Taunton, rode on the train right to the ship.

Jim Cary: And the worst part, one of the worst parts of it was that, I don't know, some of the companies got put on in an orderly fashion, but when it came to our company, C Company, they got in a great big hurry and jammed everybody in there, and the thing got messed up. You had people from other units mixed in with your own people, and you lost your command structure. The NCOs were not your NCOs, they were somebody else’s, and it was a mess trying to keep the place clean. And they did pack them in there in pretty difficult conditions.

Ruby Goldstein: One on top of another.

Jim Cary: They had a little room to shoot dice in the middle of the floor and so forth, but, you know, how long did that trip take us? I thought it was about a week, but some guy was trying to tell me yesterday it was three weeks, I don’t believe that.

Ruby Goldstein: I said 11 days.

Jim Cary: Eleven. That sounds a little more reasonable.

Ruby Goldstein: When we got to Gouroch, Scotland.

Jim Cary: We were doing a lot of zigzagging...

Ruby Goldstein: Oh yes.

Jim Cary: We came into Scotland.

Ruby Goldstein: Right, Gouroch.

Jim Cary: The Firth of Forth or Firth of Clyde, I can't remember which; whichever one is on the western side...

Ruby Goldstein: Then there were girls from the Red Cross on the platform at the train station.

Jim Cary: They had a bagpipe band out there to greet us.

Ruby Goldstein: Right. I know, I danced with one of the girls.

Aaron Elson: Really? They had bagpipes out to greet you?

Jim Cary: Oh yeah, yeah. They marched up and down, and countermarched. We thought it was great.

Ruby Goldstein: That’s a great welcome.

Jim Cary: Then we came down by train to Swindon barracks.

Aaron Elson: Did you get any time in town in Swindon?

Jim Cary: Oh yeah. Not immediately, but as soon as we could, I remember one of the first things we did was take the company and get ‘em out and just take them for a walk, so everybody could see a little of the countryside. They were all anxious to see it and loosen up a little bit, get some fresh air after being on that ship and the train. You know, being on a rough sea passage is not so bad if you can get out in the fresh air, but so many of the guys couldn’t. We had one officer, do you remember Hiatt?

Ruby Goldstein: Hiatt, yes. [Lambert Hiatt was a lieutenant in D Company.]

Jim Cary: God, the day that he got on that ship he started throwing up and he never stopped until...

Ruby Goldstein: I was sick for five days.

Jim Cary: Were you? I got in that in-between state; I'd keep going back out in the fresh air and I finally got over it.

Ruby Goldstein: I come up one day, I was posting guard, what are you gonna guard against, is somebody going to attack you on the ship? But we had to post the guard there; you were supposed to, and we’d post the guard, and you stepped in and went to open the door; the damn water came over, I couldn't open the door. It hit it so hard we hit the door. I thought we’re gonna get drowned. But we rode, we rode some waves, that was rough. First you were up there looking down, then you were down there looking up, that’s how high those waves were. Real rough. Hey, we survived that crossing. Coming back was a lot different.

Aaron Elson: What did you come back on, the Queen Mary?

Ruby Goldstein: I came back on the Ile de France.

Aaron Elson: How did they get the tanks over? You went over with the same tanks you trained with?

Jim Cary: No. Tanks were shipped over en masse. They had these supply depots of just mile after mile of different types of equipment. Then your supply officer, in our case Harry Gray, went and drew, I don’t know what the requisition said, but got the requisite number of tanks and they were given to us, and they were all gummed up with Cosmolene and so forth, and you had to clean them up and put everything in working order.

You know, the whole war hinged on that Battle of the Atlantic. If they hadn’t won that, then we wouldn't have won the war. As one officer explained to us in an orientation lecture in Benning, if we can get the material there, we can win the war. If we can’t, we can’t.