A few newsletters ago I wrote about loot, and a conversation in which 712th Tank Battalion veteran Andy Rego described an accordion he brought home from the war. That conversation was part of a broader interview with four C Company veterans — A.P. Lounsberry, Otha Martin, Andy Rego and Ralph Tambaro — at the 1993 battalion reunion in Orlando, Florida.

This is how the conversation began. When Lounsberry said he was from Louisiana, I probably shouldn’t have asked if he knew Richard Howell, since Howell, who was from Louisiana, was in Headquarters Company and Lounsberry was in C Company, and, as Otha Martin was about to explain, the companies were often spread over a wide geographical area, not to mention Louisiana is a pretty big place. Howell was killed on the battalion’s first day in combat, and I was interested in learning about him because his widow, Lillian, who never remarried; and daughter, Wanda, were at the first two reunions I attended. The question opened the door to some schooling by Otha.

“The 712th was spread all over the 90th Division,” he said, with one company attached to each regiment. The division had three regiments — the 357th, 358th and 359th — and one medium tank company was attached to each regiment.

“Now there’s three medium tank companies [A, B and C] and D Company, light tanks,” Otha said. “They’re recon. They’re not supposed to get on out there in a pitched fight. They’re supposed to hit and run, see what’s out there … let us know what we’re up against.

“A Company was attached to a regiment, generally 359, wasn’t it? And B Company, they may have switched some, but 358. And we most of the time were with the 357. And … then there’s three battalions … in each regiment, so that made one platoon, three platoons in a company of medium tanks, one platoon would be with one battalion of infantry. We were spread over a lot of miles. You see, an A Company man, or a B Company man, or even some of our own C Company people, they might be 18 miles from us, and maybe in fact we don’t know what they’re doing, or they don’t know what we’re doing, and they might have had a whale of a fight and we don’t know a thing about it. And that’s just the way it was. You can talk to people and they might not be so wide apart, but … if somebody’s a quarter of a mile up there, he won’t know what went on down here. I’m just telling you that because one man can’t tell you the whole story of the 712th.”

“When I joined the outfit I was a radio man,” Otha said. “I went to radio school in England. And then I was a radio man until, I don’t remember the date, such time as Captain Sheppard come by and said, ‘Get your stuff.’ I was a gunner, too, and went through the gunnery school and everything. … Well, when you get your stuff, a musette bag, that’s what armored people had, a little bag, and our bedroll, that’s your stuff, that’s all of it. So I went to Number 2 tank in second platoon, and this was the driver at the time.”

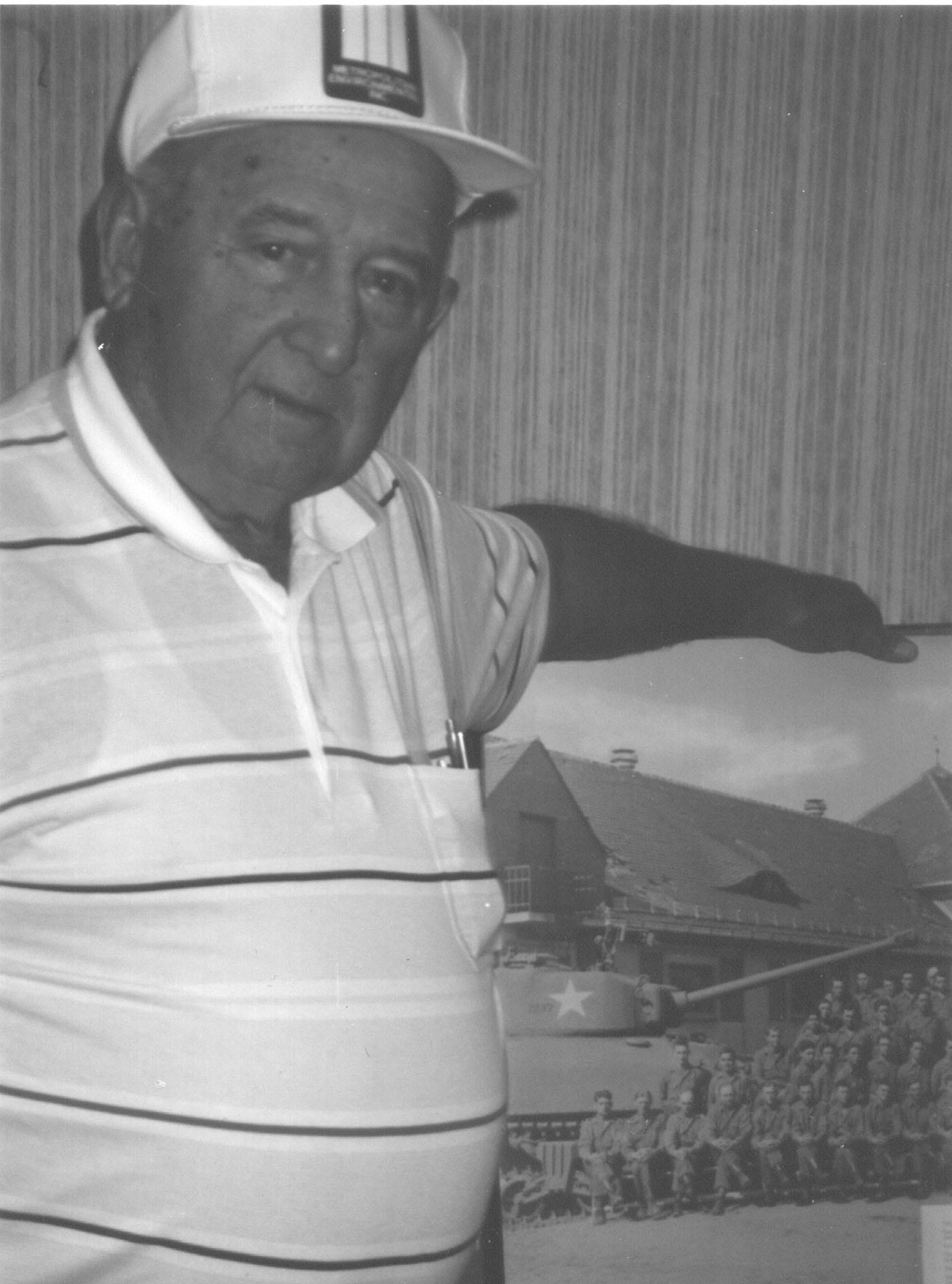

“Your name is?” I asked the veteran at whom Otha was looking.

“Ralph Tambaro.”

“So I went in as the gunner,” Otha said. “See, the gunner, did Peck get killed or just wounded?”

“He got wounded,” Tambaro said.

“But he never did come back,” Otha said. “I replaced him. … And I stayed in until the tank commander, who was named Wallace Brown, he was from Virginia, and he got hurt. Then I took the tank, I’m tank commander then, until such time as the war’s over.”

George Peck was wounded on Sept. 8, 1944, and Fred Putnam was killed when their tank was knocked out in an engagement with the 106th Panzer Brigade. The incident is described in my Substack titled Memorial Day 2024, Part 7, in my archive.

“Where was Peck wounded?” I asked (I would hear about the battle at Mairy in many unconnected interviews over several years, as this was one of the few times that most of the battalion was in one place).

“It was before we got to Metz,” Otha said, “because when I joined the outfit, they was sitting out in an apple orchard. I’m gonna say it was early in September when Peck was wounded.”

(After the battle at Mairy, the battalion remained west of the Moselle River as the Third Army probed for a spot to cross the river near the fortresses of Metz, including Fort Koenigsmacher.")

“Could it have been at Mairy?” I asked.

“I can’t remember,” Tambaro said. “All I remember was there was a little pine wooded area that we were in that night, and then we pulled out of the pine area and went up there on the hill and that’s where we got hit.”

“I’m gonna guess that it wasn’t long after he was hit,” Otha said, “because they wouldn’t let the tank go long without a crew member. So I went in and I joined them, and it was before we took Metz, before we went into Maizieres [Maizieres les Metz]. We was setting out there, and they run out of fuel. I mean the fuel got low [badly needed gas supplies was being diverted to Operation Market Garden, which was taking place in Holland and is depicted in the movie “A Bridge too Far”], and we was setting out there waiting. It was in the apple orchards. And the German planes were coming down and strafing. Artillery had Piper Cubs; you know what a Piper Cub is? A Piper Cub had one man in it, he had a couple of hand grenades and a .45, and that’s about all the weapons he had. But … his job wasn’t to fight, it’s to spot the targets from the air, and radio the artillery batteries.

“Well, them Germans knew … what that Cub was up there for, and they would get after him. He didn’t have nothing to fight ‘em with; he isn’t no match for no fighter plane, so he just had to get away.

“And one time there was one up there, he had given them a target down there, well, they’re working their computer and they’re working it all out, and they’re shootin’ at him from the ground. And he got out of humor, and he told ‘em, ‘Damn it to hell, quit computin’ and start shootin’.” But this fighter plane come in after that Cub, and that Cub went right in again, remember, we were in a little old village, he went right in there and made a sharp turn, and that German fighter plane followed him in there, and when he gets in there he can’t turn that short, he crashes into a hill and the little Cub flies back up, and they give him credit for a kill. He put a swastika on his little Cub.”

“You saw that?” I asked.

“Well, no. We may have seen it, but we didn’t know what all went on. We’s sitting out there waiting on gas.”

[I don’t know about the Piper Cub getting credit for a kill, but the pilot saying “Quit computin’ and start shootin’” took place over the Falaise Gap in mid-August where the entire German 7th Army was massed in a valley, and has become a part of 90th Infantry Division lore.]

Possum v. ax handle

Later in the conversation, after the talk had shifted to the battle at Pfaffenheck on March 16, 1945, and the subsequent crossing of the Rhine, I asked about the Battle of the Bulge.

“Go back a little bit, to the Bulge,” I said. “Where was the second platoon at that time?”

“When we went to the Bulge?” Otha said. “The whole outfit went to the Bulge, 90th Division and the 712th, too, all of them. See, we was across the Saar River. They had ferried us across; they couldn’t keep a bridgehead, and they ferried us across. They sent the infantry across in boats, then they ferried us across. And we stayed in Dillingen. How many days did we stay over there?”

“I don’t know,” Andy Rego said. “It couldn’t have been more than two weeks over there.”

[Incidentally, my father , Lieutenant Maurice Elson, was wounded at Dillingen on December 10, 1944. The little known battle of Dillingen was a major event in the history of the 712th Tank Battalion, when they crossed the Saar, fought for the city and then had to give up the substantial progress they had made and retreat back across the Saar and head north into the Battle of the Bulge. The battalion’s commanding officer, Colonel George Randolph, was given the option of destroying all the tanks if they couldn’t be brought back across the river. With the help of artillery, the battalion got all of its tanks back across with the exception of two that had to be destroyed. Little did I know that I was about to hear the story of one of those tanks.]

“It was something like that,” Otha said. But then, while we was over there across the Saar, the Germans broke through in the Belgian Bulge, up near Bastogne, St. Vith. And they pulled us back. We still didn’t have a bridge, and they ferried us back.”

“Jack Green poured water in his gasoline over there, and they had to set the goddamn thing on fire,” Rego said.

“Burnt the tank and left it over there,” Otha said.

“They dumped water in the gas tank at night,” Rego said. “One of his crew, when they were loading gasoline; you had to load the gasoline at night, hell, you didn’t load it in the daytime. I don’t know how the hell he got ahold of five gallons of water, but he dumped it in. It wouldn’t run, so they just burned it up.

“We pulled back,” Otha said, “and I don’t know how long we stayed, and then went north.”

“It was one hell of a drive, when we left down in that village and went up to the Bulge. We were third defense there for a long while. Then we were second defense. Then we moved up to first defense.”

“Then we started moving north,” Otha said, “and we moved through Luxembourg City. What’d we move, a hundred miles, into Belgium, see. Three divisions. The 90th, Fourth Armored, and I think it was the 35th Infantry, out of the Third Army.

“The Bulge was in the First Army sector. It wasn’t on us. And we moved up there, and we relieved the 26th Division, the YD Division, the Yankee Division.

“I don’t know how many days it was that we was back from across the Saar before we went north, but when we did, we started and we moved, I’m gonna say 100 miles, or maybe a little more than 100 miles. So we went through Luxembourg City. This is in December, and the damn snow was some deep, and packed down on the road, and as we’re going through Luxembourg City we had to make a hard left. Raymond Thompson was [Byrl] Rudd’s driver, he’s an Ohio boy. He had a 76-millimeter with a long barrel, and Thompson, when they turned, made this mistake, and the tank slid off [the road], and there was a house. Well, that 76-millimeter gun had a muzzle brake that looked like a basket, and it went through the wall. And there’s a man and a woman in bed in there, and it went over their bed and missed them by about a foot.

“But we moved on through Luxembourg City and on into Belgium, and then, I can’t tell you the name of the little village, but there was just two or three farmhouses there, and we relieved the 26th Division from there, and started to push toward Bastogne.”

“We you in any firefights?” I asked.

“In the Bulge? Yes, they were steady,” Otha said. “All the time. Because they were trying to get through to Antwerp, or somewhere on the coast. And they had the 26th Division in bad shape. When we got there, we were at full strength. When the 26th moved a gun, we set one down, took the reading off their gun and put it on ours. The Germans never knew when we came. So they hit us head on, and we knocked the hell out of them. That broke them right there. They never did make another attempt.

“They didn’t know that the 26th had been relieved. They’s fighting the Third Army out there now. And at the risk of being accused of being boastful, there ain’t nobody equal to the Third Army. It was the finest fighting force this world ever saw. There wasn’t a force on earth could handle the Third Army and George Patton.

“Did you ever hear Patton speak?” I asked.

“He was hell,” Otha said. “He’d tell you real quick how to whip the Germans. We set down in the snow, we took our steel helmets off and set ‘em down in the snow and sat on ‘em to keep from sitting in the snow. The whole 90th Division and half the 712th Tank Battalion was there, and he made us a speech. He said the way to whip them damn Germans was to kick their ass up one hill and kick it down the next one. That’s what he tried to do. He believed it. And the Germans feared Patton like a possum fears a ax handle.”

“Were you wounded at any point?” I asked.

“Never,” Otha said. “Byrl Rudd [the platoon sergeant] eased up to me one morning and he said, ‘Hey, you and me went all the way and we never even got a Purple Heart.’

“I told him, ‘Byrl, I didn’t want no Purple Heart. That’s the last thing I want.’

“There’s a lot of things that a man can laugh about now, that wouldn't have been a bit funny back when it happened. A lot of people say, well, veterans never talk to them. Most of them don't. They don't talk much. The reason they don't talk is, they couldn't get the picture over to somebody that wasn't there. They talk to each other. They know what I'm talking about, and I know what they're saying. Somebody that wasn't there, he would think that you're making that story up.”

Old Betsy

This wide-ranging conversation touched upon another incident in the company’s history, just after the battalion crossed the Rhine and were in a town, half of which was held by the Germans and the other half by the 90th Division.

One of the platoon’s members, Aaron “Souvenir” Brown, was on guard one morning, and “he had a shotgun,” Rego said.

“Him and Wes Haines,” Otha said. “Him and Wes Haines both had double-barreled shotguns. Very bad weapons close.”

“They was holding this town, and Souvenir Brown was on guard, and the Germans was coming down the street,” Rego said, “and from what I’m told, I didn’t see it or witness it…”

“I saw it,” Otha said.

“And he fired both barrels,” Rego said. “He knocked fourteen men down.”

“I'll tell you,” Otha said. “Rudd's tank was sittin' here, and I think No. 2 tank was sitting there even, and it's a cobblestone street. And Wes Haines was on guard in one tank and Souvenir Brown in another, and Haines, they could hear 'em. The Germans had half the town, we had half the town, and they’s wearin’ hobnail shoes on these cobblestone streets, they sound like a milk horse coming up there. And Haines, they had all four barrels loaded with buckshot. And they're waitin’. Haines said, ‘Let 'em get close, Brown, let 'em get close.’ And they come right on up there, they were just gonna take our part of the town back, when they come up real close, now each one of 'em had .50 caliber machine guns on top of the tank, but they had these shotguns up there, too. They got up real close; Haines said ‘Let 'em have it, Brown,’ they pulled all of them off in there, and they knocked them down way back there. And they got one of them, they got him down in a basement where some of us was cooking supper. And he could speak English. He had been to the States, he spoke English real well. And he's a bellyaching about gettin' shot, said it was against the rules of the Geneva Convention to shoot a man with a shotgun. Well, Haines called this double-barreled shotgun he had, he'd got it in the stock, the firing scorched the stocks, and it's charred, you know. Haines, he was really different, no question, Haines comes swinging in there, somebody'd relieved him on the tank, he come swinging in, and he called that swamp gun Old Betsy. He told him, ‘You Kraut eatin' sonofabitch,’ he said, ‘If I hear any more bellyachin' outta you, me an' Ol' Betsy here is gonna try your case.’ And he would, he'd have blowed him plum in two. But they was just a little bit unorthodox.”

Postscript: According to a google search, the use of a shotgun in World War 2 was not against the Geneva Convention.

*“Tough Ombres: The Story of the 90th Infantry Division,” published by Stars and Stripes in 1945, contains this description of the Falaise Gap:

During Aug 20, the 90th sat on a "Balcony of Death" extending from Bon Menil through Chambois, pouring death into the Germans running the murderous gauntlet. The frantic enemy was initiated by the guns of the 358th at Ste Eugenie-Bon Menil, pummeled by the 359th at Chambois, mauled by the 3rd Bn of the 358th northeast of the town.

The Tough 'Ombres first made contact with another of their Allies, the Poles, when Co L, 359th Inf, which had reached a position west of Chambois and was blocking the road from Trun, was passed through by reconnaissance elements of a Polish armored brigade. This brigade had been cut off by the Germans, and for several days was supplied by the 90th and by the air forces.

If the infantry is Queen of Battle, then artillery is King. And Chambois, which afforded perfect observation, was a dish fit for any king. Our artillery chewed up and swallowed the three-mile valley. Frequently, during the afternoon of Aug 20, firing ceased to permit wholesale surrender of Germans.

First Lt. William R. Matthews of Lawton, Okla, one of the air liaison pilots for the 344th F A Bn, was credited with starting a new motto for the division artillery. When he had spotted one target and fire was a trifle slow in coming, Matthews howled into his radio microphone, "Quit computin' and start shootin!"