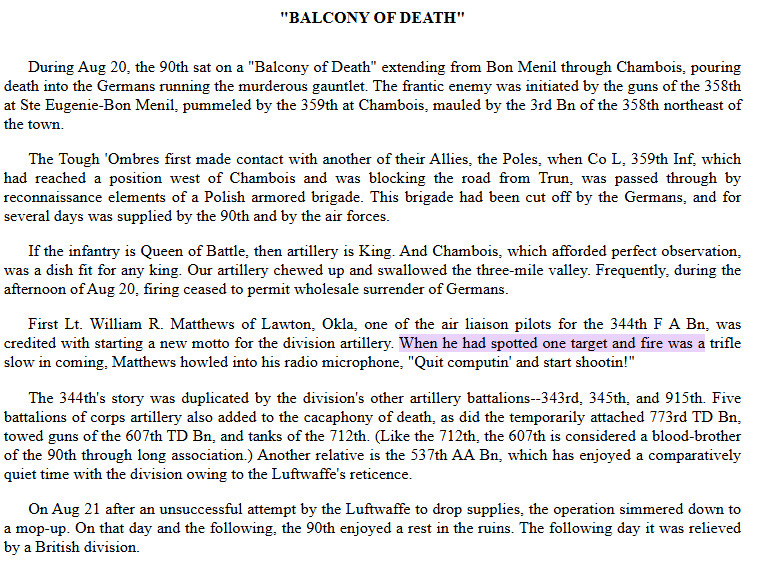

A funny thing happened on the way to my previous Substack. While I was googling in search of some confirmation that “Quit computin’ and start shootin’” was indeed an iconic piece of 90th Infantry Division lore [actually I was searching on Bing but googling seems to be more acceptable as a verb) At any rate, my belief about the phrase was confirmed in the following passage from “Tough Ombres,” a booklet put out by Stars and Stripes in 1944 or ‘45. Then I noticed one other thing in the passage that had a connection to a completely different interview.

At one of the 90th Division reunions I attended in the early Nineties, Charles Bryan came up to me and said something like “You’re an author; I’d like your opinion on this story I wrote for my grandchildren,” and he gave me a copy of a manuscript. It turned out to be one of the best World War 2 memoirs I’d read and from what I understand his granddaughter published a limited edition of some 200 copies. I forget what it was called and my copy of the manuscript is in storage, but after I read it I wanted to interview Colonel Bryan, so I visited him on Johns Island, in South Carolina.

He had risen in rank from lieutenant to captain to colonel in command of a battalion of the 90th, but when he was a captain he commanded Company L, I’m guessing with the 359th Infantry Regiment. That’s when the bells started ringing in my head, ding ding ding, when I read the second paragraph of the excerpt above: “The Tough Ombres made contact with another of their Allies, the Poles, when Co. L of the 359th Inf., which had reached a position west of Chambois and was blocking the road from Trun, was passed through by reconnaissance elements of a Polish armored brigade.”

While I recorded my interview with Colonel Bryan, he made the following remark while the recorder was off. He mentioned meeting up with the Poles at the Falaise Gap, and that they handed over one German prisoner. He said he asked why there was only one prisoner and was told it was because “we ran out of ammunition.”

Now, this may have been true or the Polish officer may have been kidding, but I have no doubt that this was said. It got me to thinking about the disconnect, as well as the corroboration and elaboration, between documented history, the kind derived from after action reports and official accounts, and the kind of personal narratives that abound in memoirs and flowed at reunions.

And while I was going through the dozen conversation transcripts from that 1992 Orlando reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I came across a passage that was related thematically to this. I was speaking with Neal Vaughn and Budd Squires, both of A Company.

“Poland had a few army units of their own, that trained in England,” Neal said. “One day we took some prisoners, and this one young boy, he was in a German tank crew, and he knew these others that were in this Polish unit, they took his German coat off and he put on one of theirs and went with them. I thought that was kind of a little different.”

“When we went into Czechoslovakia,” Budd said, “we were one of the first units across the Czech border; we ran a tank force in there and then came back. But we went into Czechoslovakia, and we hit a town; they had all the white flags up, and they had the Germans tied up to fenceposts, wagon wheels, everything. And we got into town and this one guy came over and was talking to [Lieutenant Bob] Hagerty, and then Bob says he didn’t understand him, so then he started talking German.

“Bob said, ‘What did he say?’ I said, ‘He’s got all these prisoners and he wants to give them to you.’

“Bob said, ‘Tell him that we can’t take any prisoners. We ain’t got nowhere to put them. We’ve got to wait till the next outfit gets here.’

“This guy says, ‘That’s all right. we’ll take them back. But we’ll take ‘em to the woods.’

“I said to Bob, ‘They’re gonna take ‘em back.’

“Bob said, ‘That’s fine.’

“I said, ‘No it isn’t. They’re gonna take ‘em to the woods. In other words, they’re gonna kill them all.’

“Bob said, ‘They can’t do that.’ You know how Hagerty was, he was a real staunch Christian. He didn’t go for that shit.

“I don’t remember what the hell we did. I think we left somebody there to take care of them. They had them tied to wagon wheels, and these little Czech kids were going by and they were going ‘Heil Hitler.’ and they’re tied up to fenceposts, tied up to wagon wheels and everything.

“And that's the first ice cream I had all the while I was over there. The Czechs came out with some ice cream for us. Jesus Christ, was that good.

“When the war ended, we were, what, 20 miles from Prague, I think, and we had an order to halt and let the Russians come in to us. The Germans didn't want to give up to the Russians, so they kept coming back to us. And we had a big area, big fields full of German prisoners, and the goddamn Czechs, they'd go up in the woods and snipe at 'em, pick 'em off. Well, they didn't have much love for them. They'd get in the woods and snipe at 'em. That was quite a deal.”