National Public Radio has been playing the theme from “Chariots of Fire” during its coverage of the Paris Olympics, which brought to mind one of the stories in my most recent book, “Prisoners of War: An Oral History.”

The Scottish Olympian and Christian missionary Liddell, whose life is the basis of “Chariots of Fire,” died of a brain tumor in the Weihsien concentration camp where he was interned in China.

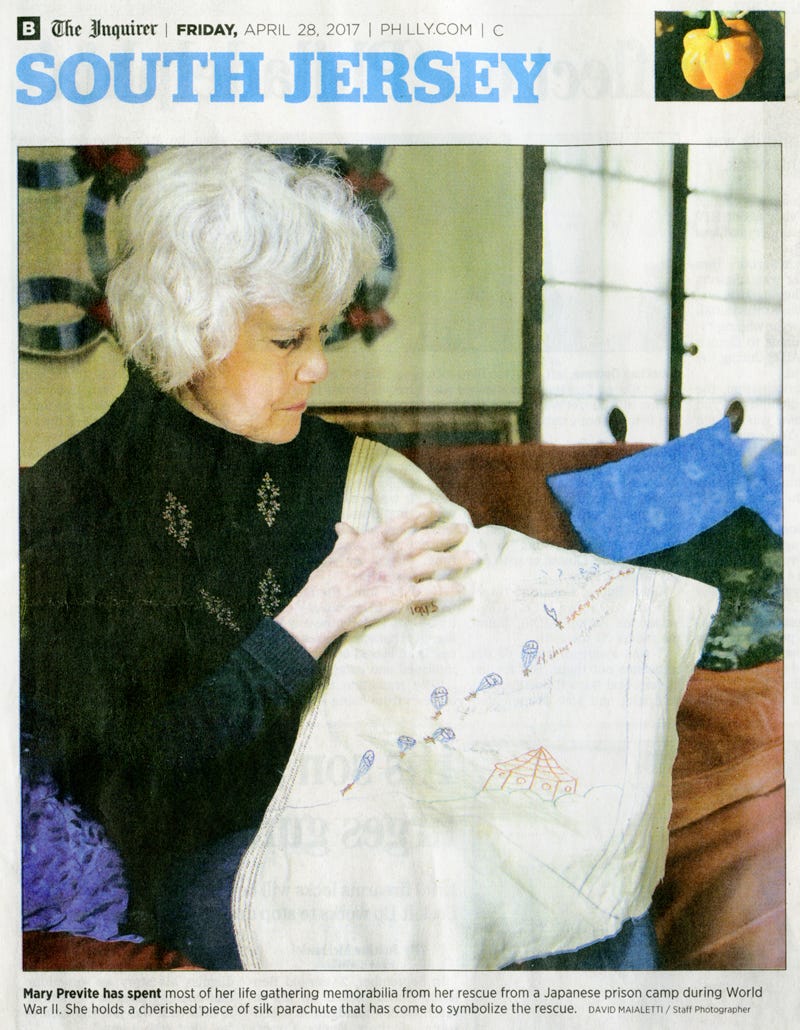

Mary Previte was a 9 year old girl when the Japanese took over the school in China for children of missionaries and spent three years in the Weihsien camp. I never interviewed Mary but I recorded two talks she gave, one at a POW/MIA ceremony at the Lyons, New Jersey, VA Medical Center and the other at a program of the World War 2 Lecture Institute organized by my friend Brandon Traister. I used the two speeches as the basis for a chapter in “Prisoners of War.”

Audio: Mary Previte

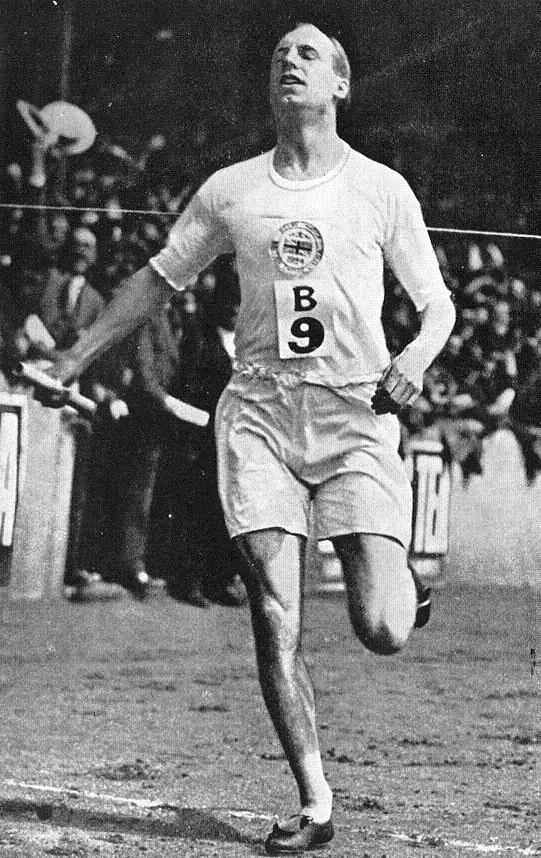

Well, the teachers were not the only heroes in this place. One of the heroes in this concentration camp was a very, very famous person called Eric Liddell. Some of you may have seen the movie Chariots of Fire that won I don’t know how many Academy Awards more than 20 years ago I think now. Eric Liddell was the Olympic athlete from Scotland who won a gold medal in the 1924 Olympics in Paris. He would not run on Sunday so he switched from one race he was expected to win to one that he wasn’t quite as adept in but won the gold medal. Eric Liddell became a missionary in China. Actually he was born in China, his parents were missionaries, and when he became a missionary to China the Japanese were rounding people up and getting ready to put them in concentration camps. Eric Liddell was brought to the Weihsien concentration camp.

We children called him Uncle Eric. He had anticipated there was trouble coming and had shipped his wife and children to Canada before the roundup came, so he was there without his wife and children.

He was a saint if ever there was a saint. A devout, god-fearing man whose favorite preaching was from the Sermon on the Mount. Can you imagine in a concentration camp with Japanese guards around teaching from Jesus’ words, Love your enemy.

Uncle Eric would lead various games and coordinate games and activities for the children, races and all kinds, if you had any kind of broken equipment, and there was very little equipment of any kind, Uncle Eric would fix it. I don’t think there was anybody that was more admired in the Weihsien concentration camp than Uncle Eric and he died in that camp. Not from abuse but from a brain tumor. He never saw his wife and children again. He was certainly one of the heroes of Weihsien.

Another set of heroes was the Salvation Army band. Now the Salvation Army band was rounded up like everybody else. They were missionaries in China, in the Beijing area, and when Brigadier Frank heard that everyone was being rounded up and marched to trucks or trains off to a concentration camp, he sent the message out: Anybody that has a musical instrument take it with you, bring it, wrap it in a blanket or whatever. Bring your musical instrument. Let’s make sure we have music in this place. Well, the Salvation Army band gets to the concentration camp and they formed a band, the Salvation Army band.

Some of our classmates, the boys, by the way who are still living, played in the Salvation Army band. Brigadier Frank said, “We’re gonna win this war, so when we do, we must have a victory medley.” Well, what should that be? They said, let’s serenade whoever’s gonna win the war and rescue us. Nobody knew who’s gonna win the war. They said it could be America. It could be England. It could be China. It could be Russia. All right, let’s put four national anthems together into a victory medley and we will put it with Happy Days are Here Again, and maybe something like Onward Christian Soldiers, and they would practice every Tuesday night outside the Japanese commandant’s office preparing for when we were liberated. And every Tuesday night they were playing except they weren’t allowed to play national anthems. So they would play all the harmony but not the melody, practicing for the day that we would be liberated.

As the war continued on, people were getting scrawny. There were men who lost as much as a hundred pounds in this concentration camp. There were people who were very, very discouraged because of the atmosphere, the feeling like the war was never going to end because obviously we were not getting the proper news coming to us. There were all kinds of rumors that would be smuggled in sometimes by the people who would carry out things, the slop from the septic tank. That would be about the only place somebody would get rumors of what was happening in the world. People were getting very, very discouraged.

I remember August 1945. I was 12 years old. The teachers had given us a break for a few weeks that summer because the heat was unbearable. Un-bearable. And as the children were getting ready to go back to school that Monday, I was lying, sick with dysentery, on the steamer trunk and I thought I heard an airplane. It couldn’t be an airplane. This was Japanese territory. Airplanes did not come over this territory. But the noise got louder. And louder. And I jumped up off the steamer trunks and ran to the barracks window and here, flying low over the treetops, was a B-24 bomber. All right, guys, what was the B-24 called?

Audience: Liberator.

Mary Previte: The Liberator. Here comes the Liberator flying low over the treetops. You could tell it was American because it had the blue star underneath, am I right, gentlemen? Well, believe me, it was instant cure for my diarrhea. I jumped up. I said 1,500 prisoners, whoever these are, as I watched, parachutes began dropping with men hanging from the parachutes out into the fields beyond the barrier wall and people falling, jumping out of that airplane. Well, I think, 1,500 prisoners, I’m gonna be Number 1 there to welcome these American gods that are dropping into the field. This is the Liberators who have come.

Do you know what the name of the airplane was? The Armored Angel. The Armored Angel. When I got to the gates of the camp, 1,499 people were there ahead of me. People were on the ground, pounding the ground with their fists. Men were ripping off their shirts, waving at this B-24 that kept circling around and continuing dropping parachutes and supplies, and just hysterical weeping, dancing, crying, and people of the camp just rushed out the gate, past armed Japanese guards, into the fields beyond the concentration camp gate to pick up these American gods, gorgeous, gorgeous American men with guns drawn and meat on their bone. And the men of the camp just picked them up on their shoulders and carried them on a bony platform of shoulders through the gates of the camp.

And when they got to the gate, up on a mound by the gate, the Salvation Army band was playing the victory medley. And when they got to that part, Oh say does that Star Spangled Banner still wave, o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave, a young American major slithered down off that platform of shoulders to a standing salute, and a young American teenager playing the trombone in the Salvation Army band crumpled to the ground and began to weep because he knew what we all knew, we were free. We were free! The land of the free! And the home of the brave

.That American team took over from the Japanese and they said to the Japanese, you will continue to be right here helping to protect the safety of these people because war, as you may recall in your history books, war continued and had been going on between the Chinese Communists and the Nationalists all over China, so the Americans said to the Japanese guards, you will stay here to see to the safety of these people. And shortly thereafter, more American men began coming in to supplement the six Americans who parachuted from the airplane and one Chinese interpreter with them, all parachuted down and took over the concentration camp.

I don’t even have words to describe how we adored those men. Do you remember how gorgeous you were when you were in the war? Now speak up, you know, did you know how gorgeous you were, did you feel the same way?

Woman in the audience: Oh yes.

Mary Previte: Gorgeous. Gorgeous. Gorgeous. We wanted to touch their skin. We wanted to cut off pieces of their hair. We wanted their insignia. We wanted pieces of parachutes. Oh, guess what. Like my sister, teenage girls pick up any stuff from the guys, they got the insignia. We little kids, 12 years old, we got the buttons. And we got pieces of parachute. Oh, we got their autograph, we followed them liked the Pied Piper. We did not let them out of our sight. I can remember, they took over the Japanese headquarters and slept in there. We would sit out there in the evening time, beg them to tell us about America. What is America like? America must be close to God. It must be close to heaven. And please tell us what Americans do. What do they eat? What do they wear? Please sing us a song. And they taught us You are my Sunshine, my only sunshine, come on, come on, You make me happy when skies are grey. You’ll never know dear, how much I love you, please don’t take my Sunshine away. See there, after what, after seventy years, I can still, well, sixty years at least, more than sixty years, I can still sing that.

You know what? The Americans arranged for us to be evacuated from the camp. The four Taylor children were among, I believe, the second planeload of prisoners out, because our parents were among those who had stayed in China during the war so they naturally were not going to evacuate us to England or America. Our parents were still in China. But we were reunited with our parents on September 11, 1945. My mother said she had to measure to see who was who we had changed so much and bless my soul, we had a little brother almost five years old that we had never seen.

I came to the United States a year later, and lived the American dream that these American soldiers, these American men, by the way, most of them were in the Office of Strategic Services which, as you may remember, was the forerunner of the CIA.

Our teachers had told us God would take care of us. My mother and father taught us from the Bible, He shall give his angels charge over you to keep you. But when I came to America I began studying history and reading about death camps and millions of people executed in horrendous ways around the world. I knew I had lived a miracle. An absolute miracle. And I would wonder, how would I find these people that liberated the concentration camp? Oh, we had their autographs, and were told where they lived, in Nebraska, or Texas, New York, or whatever. How would you find them? I would think about that often. I thought, you know, I really would like to find them if I could. This is a miracle.

Well, you know what? In 1985, for the 40th anniversary of the ending of World War II, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article I had written as the cover story of their Philadelphia Inquirer magazine talking about the concentration camp. In preparation for that story I was writing, I went to England to interview our teachers that were still living, and I said to them, now that I’m grown up, I know that you helped create a miracle. What were you thinking, when you are marched into a concentration camp in the midst of a bloody war with atrocities happening all around China? Everyone in China knew about the Rape of Nanking. I forgot to mention to you, one of the first demands when the Japanese came to our school the day after Pearl Harbor they wanted to use the teenage girls as comfort women. And I said to the principal of our elementary school when I tracked her down in England, I said, “Miss Carr, what were you thinking? What was going through your mind? You were a big person, you were grown up, you knew about war, you knew what the Japanese did to innocent women, children and civilians.” She said, “I would pray to God every night that when the Jap pits were dug out beyond the wall and they lined us up at the death pits, that when they began shooting it would be me one of the first, so I didn’t have to watch.”

I said, “Miss Carr, you never let us know such a thing. I had no idea. The only terror I knew in the concentration camp was those Alsatian dogs.” We call them German shepherds here but in China we called them Alsatians. I had no idea. I said, you know what? I have lived a miracle and I wonder how I can find those heroes. I had no idea. None at all.

Then in 1997, I was invited to run for the New Jersey Legislature to be an Assemblywoman. I had just been nominated for the position, and I was invited by my senator, who I was running with, he said, “Mary, on Saturday night there’s going to be a reunion banquet in Mount Laurel, New Jersey,” just ten minutes from my house, “a group of people called the China Burma India Veterans Association. I can’t go. Would you please go on Saturday night and give them a proclamation from the New Jersey Legislature thanking them for their service to the United States during World War II?” I said China, Burma, India Veterans Association? I never heard of this group, but that must be who rescued me. And then the prickles began going up and down my spine that maybe one of my heroes would be in that banquet.

So that week, I don’t know about you boys but we girls keep treasure boxes. Now I got my treasure box out, and I got out the names of the heroes and I typed them up on the computer, and I took the names and ranks of the six Americans who had liberated the camp, took them with me to the banquet along with the proclamation that I was going to give.

Here was a room full of men and women in their seventies and eighties in Mount Laurel ten minutes from my house and celebrating their memories from World War II in China, Burma and India. When it came my turn in front of the microphone, of course I read the proclamation and thanked them for their service to the United States during the war. And then I said I know it is not an accident that I was invited here tonight as a substitute for Senator Adler. And then I told them the story of the B-24, the Liberator, coming over the tree tops in this concentration camp to liberate 1,500 Allied prisoners during World War II. And I said to the audience, “I brought their names.” And I read the names into the microphone. I said, “Is any one of my heroes in this room tonight?” And I heard only silence. But people were weeping. And after the banquet they came and took me in their arms and they said, “You have to write this in our national magazine that you are looking for these heroes. Write down their names. Write down anything you know about them, their ranks, put it in our magazine, and we’ll send it around the United States, and put your name and address there so people can contact you, your telephone number.”

One man from the state of Maryland in that reunion got hold of that list, and he went back to Maryland and did some kind of computer search. A few days later here comes a big fat brown envelope. Every name in the United States that he could get off the Internet that matched my heroes’ names. Names, addresses and phone numbers. I think bless my soul, here I am campaigning, going door to door, trying to get myself elected to be an assemblywoman in the state legislature, now I’ve got to be definitely working on this to find my heroes from World War II. But how in the world do you do that? Hundreds of names. Do you write letters and put a self addressed stamped envelope?

And I started. Dear ... Are you the James J. Hannon or Are you the, whatever, Sammy A. Steiger who liberated the Weihsien concentration camp August 17, 1945, and then said Please return if you’re the one. And I got a few of these, not many, a few said God bless you in your search. I’m not the one but I hope you find your heroes.

Then I tried the telephone. Well, I hate answering machines. I hate, hate, hate answering machines. I would call on a Sunday, because I had MCI five cents a minute rate on Sunday so I would do very economically sensible choices of calling on Sunday night. And I’d call on Sunday night and say Are you the James J. Hannon that liberated the Weihsien concentration camp? I got nothing but answering machines. I know the people thought there was some maniac lady out there leaving these strange messages on the telephone.

I got no positive answers. But, not many weeks after the article appeared in the China Burma India magazine I get a phone call from Moorestown, New Jersey, ten minutes from my house. A lady who was nurse in Burma. She said, “I see that you’re looking for these people that liberated the camp.” She said Raymond Hanchulak lives next door to my sister in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania in a place called Bear Creek Village. So on Sunday night I called Bear Creek Village, Pennsylvania, and I said I am calling for Raymond Hanchulak. A lady answered the phone. She wanted to know the purpose of my call. When I told her, I just heard her gasp. She said “Oh my. My Raymond died last year.” Raymond Hanchulak was the medic on that mission.

This lady had not known him during the war. She had married him sometime after the war. She said, “I never knew that I was married to an American hero.” She said he was trained as a member of the Office of Strategic Services. He was trained in secrecy. She said he didn’t talk. Nothing about what he did in the military. She never knew so here was this widow who was pulling every fact I could tell her about her hero husband. She had never known any of the story. And I said ohhh, my. Widows. I could just see it happening. I was going to find widows and not heroes. It was nice to find widows and talk to them but I wasn’t going to find my heroes to say thank you to them.

I picked up my list. There was only one name, Peter Orlich, an unusual spelling. Queens, New York. Sunday night, I called Peter Orlich. A lady answered the phone. Same story. Her Pete died four years ago. Carol Orlich, the widow, she knew the whole story, oh yes, she said. She had been writing Pete Orlich all through the war, and she said when she married him, he would tell her about it. He was the youngest of the team.

Oh yes, everybody remembered Peter Orlich. He was cute, bashful, and single. Allll the girls in the camp loved Peter Orlich.

She said, “I have a present for you, Mary.” She said, “In the bottom of my dresser drawer,” she said Pete’s dresser drawer, “is a piece of silk parachute embroidered with the rescue scene of the liberation of Weihsien with the autograph of each of the heroes.” She said, “I’m going to mail it to you because it’s just sitting there in the drawer and you can have it.” By the way, the Smithsonian has that on display right now in its amazing presentation called “The Price of Freedom.” There is that Peter Orlich piece of silk parachute with each of the men dropping from the B-24 Liberator and the date, August 17, 1945. One of my greatest treasures, believe me.

All right. Now I had two widows, and I was just getting the picture. So I went to my list again. Just one Tad Nagaki, Alliance, Nebraska. On Sunday night I call and I said I’m calling for Tad Nagaki, and he said, “Speaking.” And I started to cry. I had found my first hero. A Japanese-American. A Japanese-American. Who was the Japanese interpreter on the mission. Born in America. He was born in America, an American citizen. We chatted for an hour on the telephone. I said, “What did it feel like Mr. Nagaki.”

“Call me Tad.”

“What did it feel like to have all the children following you wherever you went?” He’d been a high school athlete, oh my sake, he played baseball, he ran hurdles, he was captain of the football team. And you know what? We got him to play as our catcher. The Americans played the British. British internees and Tad Nagaki was our catcher and he wore boots and everything, oh my sake, I said, “What did it feel like when we followed you every place around?” And he said, “It felt like you put us on a pedestal.” Well, that was an understatement. We made them gods.

Now I had one hero and two widows. He said, “I can help you find Jimmy Moore.” Bless my soul. I had about 150 James Moores on my list I was going to have to call. And he says, “I’ll help you find Jimmy Moore. He lives in Dallas, Texas.” He says, “Our families have stayed good friends through the years. We send Christmas cards and all.” So he gave me Jimmy’s address.

You will never believe when I called Jimmy Moore, he said, “Mary, I am the son of Southern Baptist missionaries to China and graduated from the Chefoo School for the children of missionaries.” That was our school. Our school and he was a classmate of some of the children that were in the concentration camp. He knew some of the teachers, our head master.

He said, “I didn’t have to go to war because J. Edgar Hoover said I was in the FBI and the FBI was doing important things for security so I didn’t have to go to war, and my wife didn’t want me to go to war.” But he said, “I read in our school alumni magazine that some of our classmates were dying in the war, and I had to go. So I resigned from the FBI and signed up to go to China because they were looking for people who could speak Chinese,” and he’d grown up in China. So he said, “I went to China. In the back of my head I was making a plan of how I was going to liberate my school, and my teachers,” and he said, “When we dropped outside that concentration camp, when we got inside, one of the first people I asked to see was Mr. Bruce,” the principal or the head master of our school. Someone ought to make a movie of that, I mean, does that sound like a lie that I’m telling you? Would you even believe such a thing as that?

Now I had two heroes and two widows. I was at a dead end. I could not find Major Steiger who led this mission and I could not find James Hannon. But guess what, people. Guess what. Jimmy Moore, when the OSS was compacted and became the CIA, what do you suppose? Jimmy Moore became a spy with the CIA. I now had a professional spy working on finding the rest of my heroes. Can you believe it?

Jimmy Moore called me one day at my place of work and he said, “Mary, I’ve got some news for you. Today I found Major Stanley Steiger. He lives in Reno, Nevada.” Not too long after that he said, “Mary, I’ve got good news for you. I’ve found Jim Hannon in Yucca Valley, California.”

I had found four heroes. Each time I found one I made a rumpus. I called the local newspapers and said, “Did you know you have a hero in your midst? This is what his name is, and I will tell you what he did.” And then I sent, you know about email, emails around the world, and I said to all the former prisoners, “Here are their names and addresses. Send a birthday card, send a thank you letter, send a Christmas card. These are the people that liberated us from the concentration camp.”

You know what? It didn’t seem like enough inside my heart. I wanted to do more. That didn’t seem like enough of a thank you. And that was when I decided I was going to take a pilgrimage across America and praise my heroes and say thank you to them face to face. It took me about two years. I visited Jimmy Moore. I asked his preacher at his church if he’d let me preach on Sunday morning and tell the story to his congregation, and here was Jimmy Moore and his wife on the front seat. That congregation never knew, they’d been worshiping in a church for dozens of years and never even knew they were worshiping with an American hero.

I went on a train out to Long Island and spoke to the China Burma India Veterans Association on Long Island and honored the memory of Peter Orlich. The lady that had first contacted me, the nurse from Burma, arranged to have Helen Hanchulak come down from Bear Creek Village, Pennsylvania, to an event in the Cherry Hill area in New Jersey and I made a speech honoring the memory of Raymond Hanchulak. I flew to California and spoke at the China Burma India Veterans Association in Los Angeles, and went and visited Jim Hannon and his wife in California.

I do quite a bit of public speaking so when I was speaking at an event in California, I was able to skip over to Reno, Nevada for Major Steiger’s 83rd birthday. I had a chance to celebrate his 83rd birthday with him.

And then I flew to this little bitty town of Alliance, Nebraska, just a little dot on the map, a little farmland, and visited Tad Nagaki and said thank you to him face to face. By the way, Tad Nagaki now is the remaining one alive. I visited him in January. I flew to Alliance, Nebraska in January to celebrate his 90th birthday with him and his community, honoring this American hero. And yes, I got a picture of him with a windmill on his farm. He’s a farmer, still farming, can you believe it, at the age of 90? God bless him.

You know what? I cannot say enough thank yous to my heroes but I would like to say it to you. You who sit here served our country, served people like me here, if I can’t say it to them, I think you look a lot like them. Your skin is a little more wrinkly than it was when you were in your twenties, thirties, and your eyes and your ears might not work quite as well, but you know, I thank you every one of you that served our nation, for you are the people who saved the world.