Smoky Stuever's War, Part 2: This Man's Army

Tonsils, rattlesnakes, and a horse named Ramblin' Jack

(continued from Part 1)

Aaron Elson: How did you become a sergeant?

Smokey Stuever: Oh, that was a tricky one. When we were getting ready to leave to go to England we were in a great big auditorium; it looked like a basketball hall, and we were on one end, and on the other end was a general of the medics inspecting us, physically inspection. We had to disrobe completely naked, walk across that floor, approach his desk, and be accepted or rejected. And as I was walking up to him, he bellowed out loudly so everybody could hear, and he says, “How in the world did you ever get here?”

And I says, “I walked here, Sir.”

He says, “Don’t get cute with me, buddy. You’re not fit for this man’s Army. You’ve got the flattest feet I ever saw. And I was a medical officer in World War I. Did you ever make a overnight hike?”

I said, “I made ’em all, and on the 30-mile hike I helped carry a guy back to camp so we could all get a pass to go to town for the weekend.”

“A likely story. You take this report back to your commanding officer and we’ll see you in the hospital carrying bedpans.”

So, as I went back to camp to the office, you’re supposed to knock and state your business; I didn’t. I flung that door open and I threw that piece of paper on Sergeant Bennett’s desk, and he says, “What the hell’s the matter with you? Get the hell out of here and come in here like you’re supposed to. You want to do something about it? Step up there. Get up.”

I was ready to deck him, because him and I didn’t get along. He would always put me on KP when I didn’t need it.

By that time, Captain Davis came out of his room. “What’s all this about?”

I said, “Well, we had a physical inspection and I’m not fit for this man’s Army.”

“What do you mean? You’re one of our best soldiers. We made you sergeant. Didn’t you put that up on the board yet, Bennett?”

“No. I was going to, but we don’t need to, you ought to see ...”

“Oh,” he says, “forget that. You want to get rid of this man? He’s our best man we got around here. Come into my office.” Opens a drawer, gets a bottle out. We have one. We have another. We’re talking and talking. And he says, “You know, we had to give you a rating, because you’re Army. You’re not a temporary.” So my rating was permanent, Army, you know. “You could be a candidate for officers training school. You’ve been selected. Do you want to go?”

And I said, “No. The Army ain’t part of my life.”

He shook my hand, and he says, “What’s it gonna be, bedpans or are you gonna stay with me?”

And I said, “Oh, I sure as hell don’t want to carry bedpans.”

And oh, he hugged me, and he says, “One of these days I’ve got something to tell you that nobody knows.” And I wondered, what in the hell this is. So, before we left there, he says, “I don’t want you to tell nobody. Nobody knows this.” He says, “I fly airplanes, and I’ve joined the Air Force. I’m being transferred.” So he got transferred, when we were going to England. I don’t think he got to England with us. That’s when Laing come in.

Aaron Elson: What was [Captain Kenneth] Laing like?

Smokey Stuever: Laing was a playboy. He’d hang out at night in town, and his stooges, his buddies, as things were needed they’d run in town and get him.

I didn’t care much about him because I had a buddy, Sergeant Seitz, what the hell was his first name?

Aaron Elson: Tom?

Smokey Stuever: Yeah, Tom Seitz. Tom Seitz and Sergeant Mazure were my superiors, and two of the nicest guys you could ever be with. But what happened was Sergeant Seitz took a jeep and went about five miles to see his brother, and Captain Laing demoted him or something, and cracked the whip on him. So Sergeant Seitz asked to be transferred, so he went into C Company or one of the others, so I lost a good buddy. Sergeant Mazure was always my friend too. Like the time we came back off of maneuvers one time and I told a joke about where I worked. There was a couple of colored ladies, and I had worked for Howard Peabody Company up in Lake Forest, Illinois; that was after I left, oh, I almost said that lawyer’s name, I was working for this German and he sublet me to take care of this guy’s garden and be his chauffeur. I guess he got the pay and he gave me what he could out of it. Well, I’d left him and I worked for Peabody that summer because his private chauffeur and gardener went to Sweden to get married, and he got stuck there, the Nazis took over. He had no way of getting back. But he finally did, they smuggled him out of there, through England, and he got back home. And then I got out of there just in time, and that’s when I got drafted.

Well, anyway, where were we?

Aaron Elson: You were telling a joke.

Smokey Stuever: Oh yeah, the two colored ladies. One of them was a cook and the other one was the maid, and the cook always had a late breakfast after the boss and everybody left, then she would call me in from the garden and we’d have a brunch, you know. And so the maid was upstairs right off the kitchen up the stairs there, above the garage was their living quarters, and you could hear the bathroom, and the maid was in the bathroom, and Laura, the cook, called up to her while I was sitting there waiting and she says, “Are you coming, honey?” I guess there was a noise and she says, “Are you shittin’ honey?”

And she says, “What do you think my ass is, a beehive?”

And so, when we were coming off of a big long hike, everybody was in the bathroom at Fort Benning, I believe it was, and I told that joke when everybody was in the bathroom. Thompson was sitting on the toilet and he was kidding me about that, “Hey, Stuever, tell us that one about Honey.” And so when I told that joke, Sergeant Bennett was at the end sink shaving and everybody roared out laughing and Bennett cut himself and he was bleeding. He says, “Doggone, you Stuever, you’re going on KP.” So Sergeant Mazure stepped in and he says, “Oh, I’ve got Sergeant Stuever.” I wasn’t sergeant then yet, I was just a corporal or something, and Sergeant Mazure says, “Oh, he’s booked for this weekend, you can’t have him. He’s got to clean up the garage.” And I didn’t know that. He got me out of it.

Aaron Elson: Tell me about the time Sergeant Mazure got you gigged, is that the word? For letting some fuel vaporize before it hit the ground.

Smokey Stuever: Oh, yes. That’s, that was the excuse. He caught me up on top of a tank and it was those Chrysler tanks, they had to use that high octane gas, and it was a five-gallon can and it was about half full, and I says, “Hey, you fellas, you want to see something?” I was standing up there on the back end of that tank, and I poured it, and it wouldn’t even hit the ground, and it vaporized before it hit the ground. And so he saw that, and “Heeeeyyy, you ain’t supposed to do that. Now we’ve got you for the next thing that comes up.”

Aaron Elson: Oh, so that’s why you couldn’t do KP, because he had you gigged?

Smokey Stuever: Yeah. Well, you know, they sent a lot of guys to mechanics school up at Fort Knox, and I wanted to go. I wanted to learn more about mechanics. But those guys wouldn’t let me go, Sergeant Mazure and Sergeant Smith, he was the top sergeant then, and Sergeant Smith was pretty good. But Sergeant Mazure was always on our heels making sure that we were doing everything right. He’d walk up to you as you’re laying down underneath a truck fixing something, and you’re not supposed to look but reach over in your toolbox and pick out a three-eighths box wrench and hand it to him. Your toolbox had to be in order all the time, then he’d walk up on you in a surprise moment and pull that test on you. He wanted you to be right up there.

In the CCCs I was a cook and I was having trouble with my pituitary glands. They were swollen. My tonsils were so big that they sent me up to Fort Sheridan. They wouldn’t take them out because they’re infected, you go back and get treated and get ‘em reduced and we’ll take them out. But they wouldn’t get any better and I finally demanded that I get ‘em taken out and I went up there and I says, “I’m up here to get them damn things out and I’m not going back till I get ‘em out.”

So this doctor says, “Well, in that case, put your John Henry [he means Hancock] down here on the bottom of the page,” and he reached in the cabinet and got a bottle of booze out, he was takin’ a shot, then he seen my tongue hanging out and he says, “You want one of these?”

And I says, “Oh boy, I sure do.”

Then, when we finished toasting and drinking, I says, “How about one for the other one?”

So we had two shots. And then he put me in straits where I couldn’t move, and put a thing in my mouth and spread my jaw apart; he says, “Boy, you got a little mouth for a big guy.” And he put a bridge in there and spread my jaws apart, and then he put a little stainless steel stem in there after he put some novocaine in each tonsil, and then that little stem had a wire in it that he looped around the tonsil, and then it had like a little burr where when he cut the tonsil off that it acted like a fish hook, it wouldn’t fall down my throat. And he put them in a little cuspidor right under my chin, and he says, “Ah, there they are. How do you want ‘em? Sunnyside up? Medium rare?” And I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t say nothing. Tears rolled down my face.

And I laid in confinement in a big tent with soldiers, they just came back off of maneuvers up in Wisconsin. And I couldn’t eat nothing, all I had was ice cream and soup and oatmeal for those ten days I was there. Then when I went back I says, “I don’t want to be in the kitchen anymore with that smoke. It infected me.” We were using soft coal from Illinois and it smoked and created a lot of soot, and we had to clean those stoves and stovepipes almost every month. It was a lot of soot, dirt.

I got to be a good first cook, but I wanted to get out of there, and I went in the garage and that’s where I learned to take care of carburetors. We had an instructor in there, the CCs taught you a trade, no matter what you did, being a cook you learned to be the best, and the same way in the garage. You could learn if you wanted to. We had guys in there that just put in time, they weren’t good at re-grooving crankshafts, in those days they had babbitt inserts that went around the crankshaft bearings and then you had to learn to grind the crankshaft to a perfect roundness. They became egg-shaped years ago under the conditions they had, and you had to work on that. You learned how to correct that, and you learned how to install windows, you learned about electrical department. In those days it wasn’t a lot, but carburetors was one of the main things, and you could learn to take them apart and put them back together again, if you wanted to. And I did. And we had the best of instructors. He was in World War I and he always told about his life with going into Paris, that’s what he mostly talked about, and one time he went on a vacation and he went to Paris, as a World War I veteran, and he come back with his experiences and telling us all about it, encouraging us. He was a good man.

So I got to learn mechanics pretty good there.

Aaron Elson: Going back to the cavalry, tell me about the time that the border patrol guard went off the road and was lost for a few days...

Smokey Stuever: Oh, yeah. There was a, on the Mexican border it was patrolled by Americans and by Mexicans, and in order to make the rounds that highway would cross the border, and you’d go partially into Mexico and then some in the United States. And one area near our camp, the Mexican patrol had to cross the border and travel maybe ten miles in the United States side. And on our side, near our camp, was a highway that ran along a small river, and it had a steep bank to it and a lot of growth all along there. And there was a Mexican patrol officer and his son riding along, and they were patrolling at night, and somehow or another they disappeared. And we went looking for them and on the second or third day, we were passing the same area we went before, and we didn’t see it, but one little sergeant, Carlyle, happened to see some weeds broken down, and the stuff was so dry and brittle it was hard to see traces of a car going down there, but he was lucky, he spotted that, and here was this Mexican officer pinned under the car with a running stream nearby and his son begging for his dad, and then his son didn’t answer him no more and he was about to shoot him and himself and put himself out of misery.

Aaron Elson: Was the son trapped? Could he move?

Smokey Stuever: No. He was pinned under there too. They were really stuck under there.

Aaron Elson: How old was the son?

Smokey Stuever: The boy was maybe ten or twelve years old. It was just like the father took him along for the ride. But it was almost their last ride. It was a wonder that they didn’t get bit by rattlesnakes because there were rattlesnakes in that area. Always on our trips, there was always our fear was rattlesnakes, especially at night when we bivouacked.

One night we were bivouacked high up in the mountains, we were on maneuvers, and I buddied down with a fellow from southern Illinois, I think, yeah it was him, Lillerman was his name, and I laid my canvas pup tent, you had a pup tent you would lay down and put your blanket over it, and then you’d cover over with his blanket and buddy up, you know. And we had a nice flat rock that was heated by the sun, nice and warm. So there was a small shrubby tree nearby, and we were hearing this noise, and it was a squirrel up in that tree and he wanted to get down and get out of there but he didn’t because he knew there was a rattlesnake nearby. So we didn’t know that either, it was dark, and then about 2 o’clock in the morning they blew boots and saddle, mount up. So my buddy, I helped him get his started, then I started rolling mine up, my bedroll. And I had mine right against the rocks, and then I felt this lump and here was a great big snake. I didn’t finish rolling. I threw the blanket on the horse and everything on the horse and we took off. There was a big rattlesnake, crawled under there for warmth.

But I had the closest encounter of my life with a rattlesnake one time. We rode all morning long and finally at noontime were so tired, we come to a great oasis in the top of a valley, there was a lake up there, and big oak trees, it was like a picnic area, and everybody was scattered all around in the shade. We had a lot of maneuvers with the Air Force out of San Diego, they would try to spot us. We were trying to camouflage ourselves, and when they would spot us they would drop little bags of flour and then we were destroyed, if they found us. But as we approached that lake and those big trees, I swung around a big tree, my buddies was on this side and so I sat down without looking and I put my hand down to support myself to sit and I’m watching my horse, and he was snortin’. He could smell something. And when I looked over there, I had my hand inside of a big rattlesnake and he had his head up like this, but he couldn’t bite me because some animal or somebody had almost cut him in half; he had just enough flesh that he could raise his head, he had his mouth open and going like this. And I got out of there, and we had a fellow from Texas, he was a Sergeant Pettis, he was like a real full-blooded Mexican, and he’d go around with a knife between his teeth and that. Oh, boy. He was in his glory with that rattlesnake. He skinned it and he got salt from the cook and he salted it all down and rolled it up in a little ball, so when he got back to camp he made a nice belt out of it. But in the meantime, he cut it up and he fried it in his skillet, I mean his mess kit, and he offered me a piece. “Come on! Come on! You should taste it. It was your snake.”

So I went and ate some. It tasted like fried chicken.

Aaron Elson: How about scorpions?

Smokey Stuever: There were scorpions in the area. I remember we had a big tent where our clothing supplies was in, and they had it as a pet. And it would hang down by the entrance, and he made sure it wasn’t around when he did business with us ... but we had those horned toads, I guess they would take care of a scorpion, and we always kept one or two under our tent frame, we had a wooden floor and they would get underneath there and ch-ch-ch-ch, make noise once in a while at that when they’re mating or something.

When you were in the cavalry and you started serving your hitch in the cavalry, you were given a horse, assigned to you. But for six months every day you were supposed to go into the remount corral and pick out a remount and train it, and eventually ride it. It had been ridden once before the Army bought it. And with the horse, the horse was more important than a soldier because a horse costs $140 and a soldier was nothing, so it was more important that the horse got care, not the soldier. And I had picked out a horse like Black Beauty, it was all black with a white forehead, and he was a little bit like a heavy draught horse, but he was such a beautiful, smooth rider, and during the six months I was full of joy that I got such a wonderful horse, and in the evening, maybe, once in a while I’d buddy up with another fellow and we’d take a ride out into a strange place and in order to get there we had to go through a rattlesnake area, swamps, and then up a hill, and it overlooked the camp, and the sun would be shining up there, but down in the valley the lights were on. It was dark down there. So we’d have to hurry up and get back. And it was such a nice horse to have. And then when the six months was up and they issued a horse to you, it was going to be your permanent horse.

Aaron Elson: Did that horse have a name?

Smokey Stuever: No, but it had a number branded on his neck, yeah, like my Ramblin’ Jack was S2409. So after six months was up and we were all lined up to get the horse assigned to us, they said, “Oh, you can’t have that horse. That horse has been assigned to Lieutenant Clemens this morning.”

“Ohhhh, you can’t do this to me! I’ve worked hard. I’m going over the hill. The hell with you guys!”

I went by the gate. The first sergeant ran after me. He grabbed me and put his arm around me, then he says, “Boy, I know how heartbroken you must be. I wish they would change these darn regulations. But,” he says, “don’t let this, you don’t want to go to jail, you go running away. Don’t be a coward.”

When he said that, I wasn’t going to be no coward.

He says, “You see that bunch of horses over there, and that horse with his head up high like that?” He says, “That’s Ramblin’ Jack. He came from San Luis Obispo, a cavalry unit up there. He’s trained. He knows the Army. He’ll help you. You be good to him, he’ll be good to you.”

But he didn’t tell me about his meanness, and I had to find that out. He would bite you. So Ramblin’ Jack was assigned to me, and I had little difficulties with him at first, but he knew all the bugle sounds. One time we were on an exercise preparing for maneuvers, how to cross the dam, a lot of horses are fearful of crossing the dam and you had to get ‘em used to it, and old Ramblin’ Jack, he wasn’t scared of nothing. One time we came to an area where there was a very narrow passage and there was a snake up in a tree and nobody would go near it, you know. And they said, “Stuever, bring Ramblin’ Jack up here and let him see the snake.”

Boy, he went right by there, he just took me right through there and all the other horses followed me. Then when we got to a creek, we had to cross a creek, it wasn’t a creek, it was more like a river, and it had a real high, steep bank and there was deer in the area and cattle roamed in the area. And they had a little path going down that steep bank. It was higher than this ceiling in this room, it was quite steep, you know. And they couldn’t get started. Then finally the sergeant calls out to me, “Bring Ramblin’ Jack up here.” And he says, “Ramblin’ Jack is going to lead us through here. When you get going, you don’t have to push him, he’ll take us.”

He sure did.

“And I’ll be right behind you.”

I said, “If you’re not, you’ll regret it.”

And he started taking me off, and boy I had all to do to stay with him, and we get down into the water and we, I almost get him across, then he quick lays down on me, pins the gun and my legs under him. And he was very touchy if you spurred him, and I had to wear spurs, it was a regulation, but I didn’t want to wear ‘em, he didn’t like that. You couldn’t touch him with ‘em. Ohhh, I kicked him one. He got up and he was trying to bite me, oh, he was eeeeee, he was trying to take it out on me. And I got him going up the hill and made him run around a few times to get him tired out, and he wanted to get back in that water, and ohh, here they were all coming.

Then later on, when we had the real maneuvers, the blue army against the red army, we finally engaged the enemy in a big open field, then they blew charge, and when they blew charge, I was towards the back end. Old Ramblin’ Jack locked that bit in his mouth, you know they had a bit, you could pull on the curved bit and it would turn in there and it’d pinch his tongue, but he bit that thing, and I had all to do to hold on. He’s like this ... Boyyyy, he took off, and we went right through everything, the enemy, and the officers were waving, “Stop that, can’t you control that horse?”

Then finally, when I, we were out there all by ourselves and I’m trying to wear him down, you know, finally come back, and “Ohhh, you’re gonna be court-martialed, you ruined everything, the exercise is a mess!” All that crap.

And I yelled out, “I’d like to see anybody ride this horse!”

And then that changed it, “Go back to your outfit.”

See, they really cooled off. They wanted to murder me.

He was great when we were out on maneuvers, and when I was with a group they usually stuck us on the outskirts because he was a good watchdog. We bedded down under a tree near a creek and that was the worst place to be because they would come up this dry creek bed and steal our saddles and stuff, and horses if they could, and oh, this guy thought he was really going to get a prize, so he went up there and got in front of Ramblin’ Jack, and old Ramblin’ Jack got him by the arm and he’s squeezing him like a pig. We had a prisoner without any trouble. Everybody laughed and laughed, ohh there was such a noise. It was an exciting moment.

Aaron Elson: You’re a gentle, elderly man today, but you seem to have had quite a temper when you were back in the cavalry in those early ...

Smokey Stuever: Yes, oh yeah.

Aaron Elson: Did you ever get into any fights?

Smokey Stuever: Yeah, they got me in the ring a couple times, but one of my tent partners was a Winnebago Indian from Wisconsin, a full-blooded Winnebago Indian, and he was an outstanding boxer, and he loved to get me in the ring and spar with me, but he wouldn’t hurt me, you know. But he wanted me to really pick on him, you know, and I guess I upset him one time, and he let me have it. He knocked me out. But I never got in a bitter fight in the ring, but, well, trouble was, they put me in charge right away but they didn’t give me no money for it, or give me a first class rating, corporal. It took a long time till I got to Columbia, South Carolina, and then they had this sergeant, but then overseas right away I advanced to tech sergeant, which is like the master sergeant without that little diamond in it. Boy, where’s my, oh, my cap’s in my room. I’ve got it on my cap. There were three up and three down.

Aaron Elson: Did you ever get into a fight outside the ring, arguing?

Smokey Stuever: No, I never ...

Aaron Elson: How about drinking, did you ever get drunk with ...

Smokey Stuever: Oh yeah. Drinking was always on the menu. Yeah, we would go to the PX like down in Columbia, South Carolina, they closed the PX about 9 o’clock or something like that, or 8:30, and before they’d close it I had a big gallon jug under my jacket and we kept pouring the bottles in there, and I took that back to camp.

Aaron Elson: Was that beer?

Smokey Stuever: Beer, yeah. And it was Hudepohl Beer. “Vass you ever in Cincinnati?” That was on the bottle. Vas, V-A-S-S, Vass you ever in Cincinnati? In German slang. And the name was Hudepohl Beer. Yeah, we drank a lot of that, oh boy.

Then in England when we finally got into one of the neighboring taverns in the area, why we would drink ‘em dry.

Aaron Elson: Now, we’re getting towards the end of the tape, we’ve been going for 90 minutes, can you go on some more if I put a new tape in?

Smokey Stuever: Yeah, oh yeah.

Aaron Elson: This is Ed “Smokey” Stuever, second tape, today is Sept. 23rd, 2005, we’re at the 712th Tank Battalion reunion in Cincinnati. Okay, go ahead.

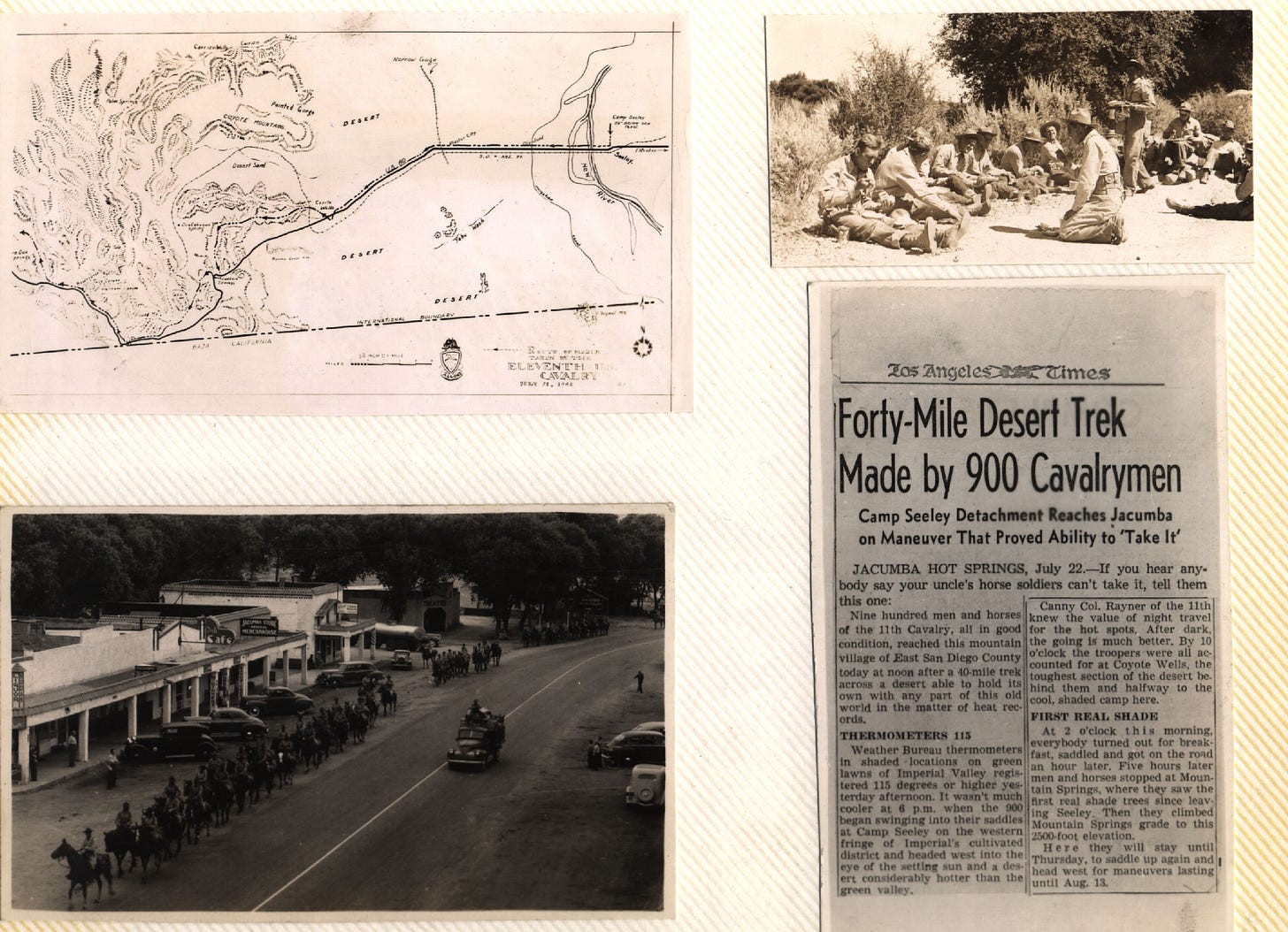

Smokey Stuever: Okay, back in my early days in the Army I was in the cavalry on the Mexican border. We were sent out to a place called Campo, California, about 50 miles straight east of San Diego along the Mexican border, and we were put in a little tent city called Camp Morena Lake. It was along a big, beautiful lake that we would go swimming in on Sunday afternoons when we had nothing to do. We were there from February till about October, November of 1941, and they built Camp Lockett right near Campo, California, which consisted of a highway intersection, and it had a grocery store, a church, and a few dwellings. And they took away the land that belonged to a rancher that I became a guest of after church when I attended church, before they started construction of Camp Lockett, and when the government possessed that land, I lost track of that rancher and his son that I became friendly with, and he showed me all the caves that Pancho Villa hid his loot in, and we went into some of them caves. I would never take that chance again. We had to crawl in there, and what do you do, you take a rock and throw it in there and if the rattlesnake didn’t rattle it was okay. And came about October of 1941, the new camp was built, new barracks, quite a few of them, and then the first squadron came down from Seeley, California, which was above the Imperial Valley, the Imperial Valley was a big agricultural area, and all irrigation from the water from the Colorado River.

When we moved there they disbanded the Morena Lake camp, and there was a lodge left there and so that became kind of a resort area, but after the war it got built up into condos and everything and people would drive from that area to Los Angeles to work every day, and that’s what created those expressways, but that’s jumping the gun.

Back to Camp Lockett. When Seeley came down, then we were reorganized, and that’s when first squadron and second squadron became one unit. And every Saturday we would have a mounted review on the big field, a big level field that had an oak tree in about the center of it over on the side, and at that time I was in the veterinarian detachment and I had a friend from Wisconsin whose name was Larry Thompson, and he was in the veterinarian detachment with me, and we rode out there ahead of the parade and we would sit by the tree in case there was a casualty we had to take care of it. And as we’re sitting under that tree waiting for the parade to begin, the tree starts shaking and the leaves falling down, the horses ran away from us back to the barn but somebody finally brought ‘em back to us. We had a little minor earthquake. A tremor. And our parade was really something. They started out at a walk. They’d pass in review, and people from San Diego and all over the area would come out and watch us, and it was quite thrilling. Everything was done strictly. Of course they walked by at a walk, then a canter, and then a gallop, and the tail end of it would be jeeps, they had some jeeps, machine guns, but they had a machine gun troop, horses, they had a lot of equipment.

Now, in September when everybody had put in six months, everybody was eligible for a leave. Well, I didn’t have no money to go home so I stuck around with some of the guys and we participated in a horse show at the San Diego County Fair which lasted ten days. All the black horses were gathered together and we transported over there, and we put on a wonderful machine gun display in front of the grandstand before the horse races would start. As we approached, we passed by at a walk and then we did the figure eights and the wagon wheels and different maneuvers, then we lined up in two lines facing opposite directions, and then the fellow up in the grandstand, the announcer would announce over the PA system, “Let’s see how quick they can dismount and fire off the first rounds of ammunition. Yesterday they did it in ten seconds.” So he would blow the whistle and we’d go about 20 paces and then he’d blow the whistle and stop and that’s when they’d start counting, and the fellows would get off and grab the machine gun and the other ones the ammunition boxes and run about ten paces forward, drop to the ground, set up the machine gun and blast off a round of, oh, quite a few shots of ammunition. And I had the job of gathering up the horses. They’d throw the reins at me and I had to keep circling around, and one time we had a replacement horse, he wasn’t used to the noise and he created quite a disturbance, and he pulled me out of the saddle and I was around the horse’s neck with my legs wrapped around, hanging on for dear life, and I got quite an ovation. I finally got the horse under control and did well, and when they were ready I rode ‘em right up to there.

Aaron Elson: You were in charge of like, you would be on one horse and you would have the reins of how many?

Smokey Stuever: Five.

Aaron Elson: Five horses?

Smokey Stuever: Yeah, five horses.

(to be continued)