“In his letters, he always ended up with, ‘Don’t forget, I love you,.’” Dot Cooney said.

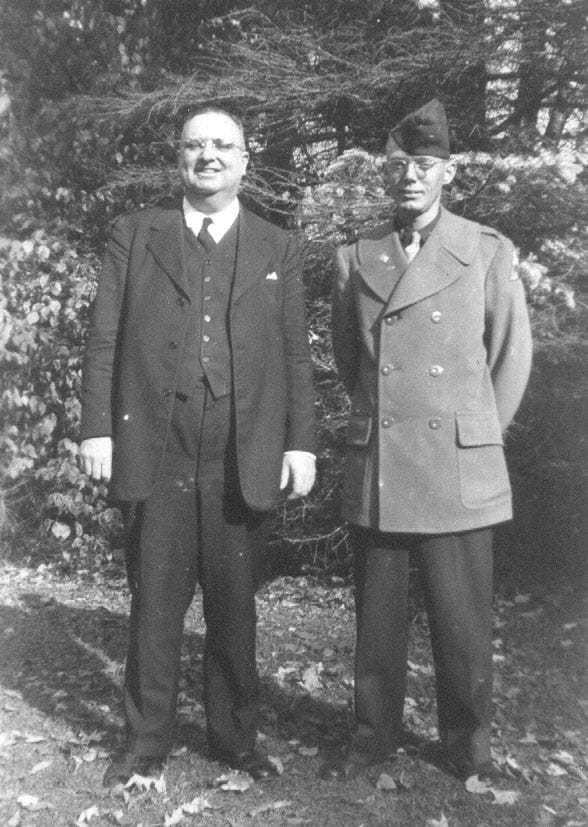

When I was growing up, my father didn’t hesitate to talk about the war. His stories were tinged with humor, even though he was wounded twice, and I can probably link his occasional bursts of temper to post traumatic stress disorder. But when he died, I only remembered a few details: that he was a replacement for the first lieutenant to be killed in his outfit; that he was wounded in Normandy and again in Dillingen, Germany; and I only remembered one name from his stories, that of a fellow lieutenant, Ed Forrest, who was killed near the end of the war. I don’t know how or why he and Ed bonded other than that they were both about the same age, in their early thirties; they were both from the Northeast, my dad from New York City and Ed from Stockbridge, Massachusetts; and I would learn later that they were wounded within a day of each other, my dad on July 27, 1944 and Ed on July 28.

Seven years after my father died I went to a reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion. I met three veterans who remembered him, and all the stories he told came back to life. At the same time I was so moved by the stories the veterans shared among themselves that I resolved to begin recording them.

In his last few years my dad lived with my sister in Pittsfield, Mass., not far from Stockbridge, and other than his declining health, I don’t know why he never made an effort to look up Ed’s family. He said he thought Ed’s father might have been a minister, and might not have approved of him going off to war, and that something about Ed gave him the impression he might not have wanted or expected to return.

“I think he had a premonition,” Dot said.

One of the things that gave my father that impression was a time Ed volunteered for a very dangerous mission, for which my dad said he didn’t know if he would have volunteered. Over the next few years I heard several accounts of what that mission might have been. Clifford Merrill, the first A Company commander, said he had a very competent officer, Ed Forrest, and that he wanted to “stir things up,” so he sent Ed’s platoon some three miles behind enemy lines, and they had to shoot their way back. Forrest Dixon, the battalion’s maintenance officer, told me a story about tank driver George Bussell running over three German motorcycles. “One of them had a side car so I thought that must be an officer,” Bussell said when I asked him about it, “so I hit him dead center,” Bussell said the motorcycles were parked outside a building and didn’t have people on them, but that was on the mission Ed led.] I learned that Bob Hagerty was a sergeant in Ed’s platoon, but he had no recollection of the mission because a hatch cover slammed down on his fingers a day or two before. And Neal Vaughn, a gunner in the platoon, said three tanks of the platoon were sent to try and find a company of infantry that the 8th Division that had lost touch with.

In 1994 I published my first book, “Tanks for the Memories.” The next year I decided to see if I could find Ed’s family. If his father was a minister, I thought, there must be some record of him in Stockbridge.

I called Information and learned there were no Forrests listed in Stockbridge, but there were three in the neighboring town of Lee. I called the first one, Elmer Forrest.

“This is out of the blue,” I said, “but I’m looking for anyone related to an Ed Forrest who was killed in World War 2.”

“He was my brother.”

“Was your father a minister?” I asked.

“No,” Elmer said. “Our father was an alcoholic.”

Now wait a minute, I thought. “My father knew Ed during the war,” I said, “and he said he thought Ed’s father might have been a minister.”

“That would be Mister Laine,” Elmer said. Mister Laine was an “old batch,” [or bachelor], and was the minister at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Stockbridge. Ed did odd jobs for the minister, Elmer said, and when he was 14 their mother died and Ed had a big fight with their father, and he moved into the rectory.

I asked Elmer if I could interview him, and he said sure, as long as I came after church on a Sunday.

Ed was Elmer’s older brother. There were four siblings. Ed was the oldest, followed two years later by a sister, Vera Louise, and five years after that by Elmer. Seven years later a fourth child, Warren, came along, but he died when he was 12 of peritonitis.

The second-to-last time she saw Eddie, Dot was working as a seamstress in a factory in Springfield, Mass., and he was on his way from Stockbridge to Worcester, Mass., to donate his collection of paperweights to his alma mater, Clark University. He stopped by but she couldn’t leave work, and he had to be back in Stockbridge at 4 to drive the minister to another church to preach. The window near Dot’s work station looked out over all of Springfield, and Eddie told her that when he drove by he would hold an American flag on top of the car so she would know it was him. She did, and saw the flag and Eddie driving by.

The next time he was home, which would be the last time he could see her before shipping out, he sent her a telegram telling her to go to the YWCA in Providence, Rhode Island, and wait for him. He finally arrived, and, she says, he proposed, but she told him something to the effect that he already had a lot on his mind, and that they should wait until he returned. His last words to her were that they would meet again, “sometime, somewhere.”

A strange thing happened on the trolley in Springfield when she went to the post office to answer his telegram. When she got off the trolley, she found a quarter in the street. After she sent the telegram, she took the trolley back to her apartment, and when she got off the trolley, she found another quarter in the street.

“I sent him one of the quarters,” Dot recalled, “and he wrote that when he was wounded, the quarter stopped a bullet. As if it were an omen.”

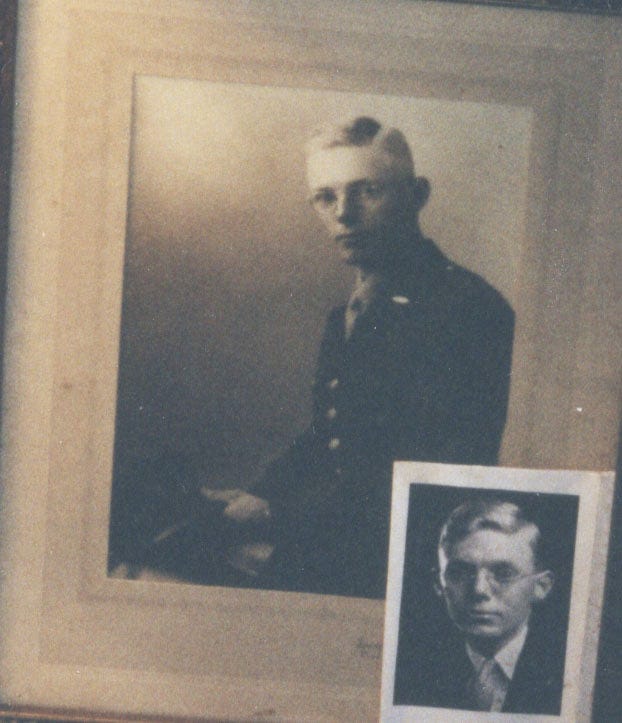

After he was drafted in 1942, Ed failed the test for officers candidate school because he was color blind, his best friend, Dave Braman, said, so he memorized the color blind test, took it again and passed. He would become one of the most respected officers in the tank battalion. He was wounded during the battle for Seves Island near Perier in Normandy.

“Ed was my platoon leader in Normandy,” Reuben Goldstein, a tank commander, said. “When I was with him, he was Number 4 tank, I was Number 5. We got up near some apple orchards, and we got a barrage [of incoming artillery]. So the first thing you do is take cover, and where are you going to take cover? The safest place is under the tank. But Ed couldn’t get back fast enough to his tank, so we went in the bushes, in the hedgerow. So I jumped in, I went right with him. I’ve got my arm around him, and they were still shelling. We’re getting it, and you’re praying that nothing hits you. But he got hit. And I didn’t know it. I had my arm around him. It’s fate. That’s all I can say it is. It’s fate. Because when I said, ‘Okay, Ed, everything’s okay, let’s get going,’ uh-uh. He was hurt. So I don’t know who the heck came up with a stretcher, we put him on the stretcher, and we got him on the road near a first aid station, and they took him away.

“He was from Massachusetts. Because they tried to contact his family [after he was killed later in the war], and I don’t think they were too happy about talking to anybody, his family, at the time. I tried to contract them.”

Elmer was drafted and was in England when he learned Eddie was also in England recovering from his wounds. He got permission to visit Eddie in the hospital, and they were walking on the grounds when an enlisted man saluted Ed. “Same to you,” Ed said under his breath. Elmer asked him what he meant and Ed said, “He’s thinking, ‘You sonofabitch,’ so I’m saying ‘Same to you.’”

I asked Elmer if Eddie had a girlfriend. He thought for a moment, and said the family thought Eddie would marry Eleanor Dusenbury, who played the organ at St. Paul’s, but she had since passed away. Then he said there was a woman Ed dated who never married and still lived in town.

Ed returned to the battalion in November, in time for the early December crossing of the Saar River near Dillingen, the battle in which my father was wounded the second time; and the Battle of the Bulge, where his company fought off nine counterattacks in the village of Oberwampach. He was in line to become A Company’s third commander, but was outranked by George Cozzens, a recent replacement. Instead he became the company executive officer.

On April 3, 1945, just five weeks before the end of the war in Europe, Ed was setting up his headquarters in the basement of a solidly built two- or three-story house in the village of Heimboldshausen, Germany, near a potash mine along the Werra River. The battalion, and troops from the 90th Division, to which it was attached, took the town in a brief firefight and moved on, chasing some SS troops who had fled. Some 32 service personnel from the tank battalion and dozens of rear-echelon troops from the 90th Infantry Division were setting up their accommodations for the night when, suddenly, someone shouted “Plane!”

I called Dorothy and asked if I could visit. But first I did a bit of research. I found Ed’s name on the town’s World War 2 monument, and on an honor roll on a wall of the church. There was an asterisk by Ed’s name and the footnote “Junior warden of the church.” (The senior warden was Rodney Procter, as in Procter & Gamble.) I visited St. Paul’s on a Saturday and the church was empty, but I signed the guest book and contacted the then-current pastor, Ted Evans, hoping he could tell me more about Mister Laine. He said he knew very little, but that if I went to the library, they had a diary that he left.

I called the library historian, Polly Pierce, and arranged to see the minister’s diary. I was primarily interested in seeing what he wrote the day Eddie was killed, but I wound up photocopying the entire diary, the photocopied pages of which are in a bin underneath my desk.

Dot said she and Eddie had a secret romance, although apparently Elmer knew about it. She didn’t even know if Eddie’s best friend, Dave, knew they were an item. This was because after working for ten years as a telephone operator in Stockbridge, a job she hated, Dot moved to Springfield, where she got a job working with fabrics, which she loved. After she moved back to Stockbridge, where she lived in the house her grandfather built on Church Street, not far from St. Paul’s, she did upholstery for many of the town’s wealthy residents, and even did the curtains for the sculptor Daniel Chester French’s studio. Norman Rockwell would wave to her when he rode his bicycle past her house, and sometimes she would even ride along. She can even be seen in a video shown at the Rockwell Museum.

Eddie was very reserved, Dot said, and he spoke little about his family. In fact, she said, she didn’t know until reading it in the first edition of my book about my father’s tank battalion that he was 14 when he moved in with Mister Laine.

I was fascinated by the minister’s diary, but there was one big problem: I had no idea who any of the people he mentioned were. So I would read passages from the photocopies to Dot, and she would tell me who the people were. For instance, a day or two after Eddie was killed, Mister Laine noted that he received a phone call from Gertrude Robinson Smith in New York telling him that her mother had died. Dot asked if I knew who Gertrude Robinson Smith was? I kind of shrugged, and she said: “Tanglewood.” (Gertrude Robinson Smith was the socialite who helped launch the Tanglewood concert venue in Lenox.)

Over the next few years I visited Dot from time to time, usually without the tape recorder. She had a minor auto accident and had to give up driving, and after falling off a ladder while trying to retrieve some fabric from the attic she sold her house, which became a bed and breakfast, and moved into senior housing, which she wasn’t happy with, so she moved again.

One day she said that she couldn’t tell me for sure, but that if I looked into it, I might find that Eddie’s mother committed suicide. The next day I called Elmer and asked if I could visit him again. He said sure, just come after church on a Sunday.

I wasn’t sure how much Elmer would even remember, as he would have been only seven at the time. We chatted for about an hour and then I decided it was time to pop the question. I asked him how his mother died.

“She committed suicide,” Elmer said. He said she found out that she was going to be committed to a sanitarium and that his father would tie the end of her nightgown around his arm so that if she got up in the middle of the night it would wake him. One night she carefully untied the knot, went out of the house and jumped into the Housatonic River. Elmer said he remembered, at 7 years old, sitting in the kitchen eating ice cream and being afraid while everyone was out searching for his mother. (Eddie and a friend would find her body after his father went right past it thinking it was a log, according to a memoir written by Eddie’s sister Vera.)

I last interviewed Dorothy in 2002, when she was 92 years old. It was the first time she went into detail about her relationship with Eddie, and about growing up with abusive parents who often argued, and how she took the job as a telephone operator, whch she hated, to help her twin brother, Don, go to Holy Cross. She said sometimes when Eddie had to drive Mister Laine to some function where he was to speak, he would drop the minister off, pick her up and they would go to Friendly’s for a bite. She remembered the first time he took her to a dance, and said she told him that he was holding her too tight. Another time they took a rowboat out to a small building on an island in the Stockbridge Bowl, the skies darkened, and they watched a tornado touch down in the nearby town of Becket.

Lieutenant Forrest had just finished setting up his company headquarters in the basement of a house in Heimboldshausen, Germany. Pete Borsenik, a mechanic, was standing in the doorway. A disabled tank and a truck with 300 five-gallon jerry cans of gasoline were parked outside. The truck was only supposed to carry 250 cans of gas, but driver Joe Fetsch figured out a way to stack them so as to fit an extra 50 cans. “It looked like a pregnant cow,” Fetsch said.

The house was one of four situated opposite a small railroad depot. Several empty ore-carrying cars were parked on a siding at the depot, along with two boxcars and two gasoline tanker cars. One of the boxcars contained material for making uniforms and the other was full of bags of black powder for artillery. The two tanker cars were empty but were filled with fumes.

At the shout of “Plane!” Fetsch climbed atop his gasoline truck and swung its ring-mounted .50 caliber machine gun around.. The next thing he knew people were digging him out from under a pile of rubble. Pete Borsenik was badly wounded, although when I met him at a reunion his marked limp was due to losing a leg to diabetes and not from the war. Ervin Ullrich, a cook who was preparing a hot meal near the railroad depot was killed and the food scattered. Wilson Eckard, whose grave would be adopted by my friend Kaye Ackermann, was killed in the explosion. The house in which Ed Forrest had just set up his headquarters collapsed.

“You’re an author,” a veteran at a 90th Infantry Division reunion said to me. “How does one go about correcting a mistake in a book?”

“I hope it’s not my book,” I said, “but that shouldn’t be difficult,”

The mistake he was referring to was a passage in John Colby’s “War From the Ground Up,” about the 90th Infantry Division, which is regarded as one of the best unit histories ever written. The passage was about a bomb causing a carload of black powder to explode.

“It wasn’t a bomb,” the veteran said. It was bullets being fired at the fighter plane attacking the village, or from strafing by the plane.

Did God just hand me an eyewitness to a key moment in my book? I wondered.

It also wasn’t the black powder, I would learn when I visited Heimboldshausen in 1999, but rather the two fume-filled tanker cars that caused the explosion. The damage was caused by the concussion, and not by flames, which is why Joe Fetsch’s truck didn’t explode.

Four of the tankers were killed (the other was medic Joseph Diorio) and of the 32 members of the battalion in the village, only three or four were not injured. Many of the 90th Division personnel were killed or injured as well.

The German fighter plane, a Messerschmitt 109, was flying so low that it was caught in the explosion and crashed into a house in the neighboring village. Orville Moody, a truck driver in the tank battalion, recalled seeing the wreckage of the plane in the building’s open basement. The pilot’s boots were all that were left, and they were still smoking. The pilot is buried in the village cemetery with a blade from the propeller of his plane for a tombstone and the epitaph “Here lies an ‘unbekannte flieger,’ or unknown flier.” After my visit to the village, the historian Walter Hassenpflug, who assisted me in my research, was able to identify the pilot, who left behind a wife and child, but that’s another story.

On one of my visits, Dot told me that while she was in Springfield, she suffered from fibroid uterine cysts that were so painful that one day she collapsed in the street.

In that 2002 interview, she told me she was in the hospital and had just had an operation – most likely a hysterectomy – when her father called and told her Eddie was killed. I asked her how she reacted.

“I was numb,” she said.

Upon returning to Stockbridge, Dot received a call from Mister Laine, who asked her to come to the rectory. “He had never done that before,” Dot said. When she arrived, the minister said, “Eddie wanted you to have this,” and he gave her Ed’s fraternity pin.

Eventually, Dot destroyed all the letters Eddie had written, which she said she now regretted doing. Interestingly, the minister noted in his diary some time later that he burned all the letters Eddie had written to him – more than a thousand over the four years Eddie was in the service.

And while he may indeed have had a premonition, it’s pretty clear to me that Eddie expected to survive the war and come home. He couldn’t have been in a safer place when he was killed, in a solid house behind the front lines, where his main responsibility was finding houses in which to billet the battalion’s service personnel. I could not say the same about the minister. Mister Laine was a chaplain in World War I, and was cited for bravery and was wounded during the Argonne offensive, according to his obituary in the New York Times. While he noted in his diary that he enjoyed displaying his memorabilia from the war, it was clear that he well knew the horrors of war. He wanted to adopt Eddie but Eddie’s father objected, and throughout his diary he chronicled Eddie’s life as if in order to be sure there was a record of Eddie’s time on earth.

Ironically, the diary could easily have been tossed in the trash. After leaving Stockbridge in 1949, Mister Laine became the chaplain at the Manlius Military Academy, near Syracuse, New York. I’m not sure when he left Manlius, but the school eventually became a prep school. At some point someone was clearing out a storage area and found a box containing a pair of diaries and some sermons. It might have been after the minister’s death. At any rate, rather than throw it away, they sent the box to the Stockbridge Library.

I’m not sure when Dot Cooney passed away; I couldn’t find an obituary online, but I don’t think it was long after that 2002 interview. I think it gave her some closure to be able to talk about Eddie and know that his memory is being kept alive. Mister Laine left Stockbridge in 1949 and was the associate rector of the Church of the Ascension in New York City when he passed away at age 83 in 1972.

Terry Cooney is the visitation minister at West Lawn United Methodist church in West Lawn PA. He's a very nice person. I don't know if he is related,but he's the only other Cooney family member I know.

I enjoy your stories.