SOTU: The view from WW2

"Roosevelt killed my son"

“You should have seen me the other day,” Morse Johnson, a sergeant in Company A, 712th Tank Battalion, wrote in a letter to his mother and sister in Cincinnati. “We were halted in the center of a town and surrounded by an ecstatic, worshiping crowd who were festooning our tanks with flowers and bestowing cognac, hard boiled eggs, etc! Perched on my tank turret with a bottle of vin rouge in one hand and a mushmelon in the other, I became a veritable political Toscanini as I would pronounce the name of some Frenchman. Then the crowd, taking their cue in part from me, would go into wild frenzies of shouting and gesturing. At such a name as ‘Laval,’ lips would curl and fingers would slice across throats and then ‘De Gaulle’ – enthusiastic cheering and scores of blown kisses testified to his popularity in that sector. It is by no means unanimous. I found ardent ‘Giraudists’ yesterday and there is still much respect for ‘le vieux soldat’ – Marechal Petain. Perhaps our authorities do not appreciate such intrusions into French politics but they would be magnifying the importance of one dirty and amused GI on the minds of people hardened and tempered by five years of torment and confusion.

“Our successes have been so swift and sure that when coupled with the Russian advances and whatever inferences can be drawn from the faces and attitudes of the countless German prisoners we have seen, we are becoming too optimistic about the finish of this mess. I try to convince myself that we will still be fighting for at least a year so that I will suffer no disillusionments but, like the rest, so ardently hope for a quick end and that such self-discipline is impossible.

“Perhaps nothing causes me more concern than the political apathy among the soldiers [the 1944 presidential election was under way]. It seems incredible but so few realize the obvious connection between their present activity and their conscientious exercise of the democratic privilege. At the best one out of ten will vote. Yesterday I became so enraged that I berated one of the nicest lads I’ve ever known. Perhaps I exaggerate the seriousness of it all but if a tragic turmoil like the present war does not inspire men to appreciate democracy and to do everything to solidify its basis, what will, short of fascism or communism?”

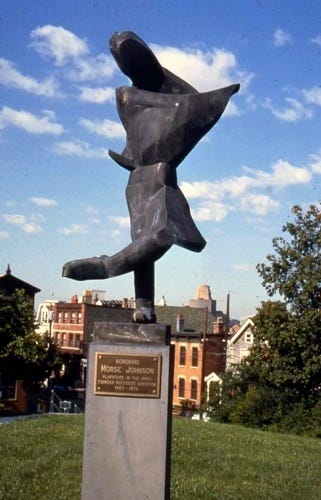

In the Mount Adams section of Cincinnati, near the Playhouse in the Park, is the only statue I know of honoring a veteran of the 712th Tank Battalion. Although he began his military service as a private in the horse cavalry, the Morse Johnson Statue does not show a soldier triumphantly riding a horse. Actually it’s kind of abstract, and reflects his life not as a soldier but as a patron of the arts

Johnson’s mother and sister saved his letters home, and he later put together a series of excerpts. In another excerpt from the excerpts, he laments the apparent disconnect between the troops fighting the war and the politics that could determine their fate.

“And how are all the Huffmans?” he asks in another letter. “I do think of you often and try to picture a typical evening meal. What do you talk about? All of these questions and images wind through my mind as I stand a guard shift or lie on my bedroll or wait on my tank for orders to move out. How much and how often all of us think of home! This should not come as news to you but perhaps with first hand emphasis it will make you better able to understand and appreciate it. I should say that conversation among soldiers at war divides down about as follows 1) 40% – actual battle experiences – strategy – guessing as to the war’s end – speculation as to our future part (all lumped together for they naturally feed into one another) 2) 25% – Home – what we liked to do in civilian life – tales of mother, brother, et al not because they are interesting but because it is a pleasure to talk about them 3) 20% gripes about the Army and about other men in the Army 4) 10% – sex, including the movies 5) 5% miscellany, including primarily sports. This is the American Army. I understand other nations have a far more politically conscious soldiery, but were I to assign a percentage for us to – call it ‘politics’ – it could not accurately be more than 2%.”

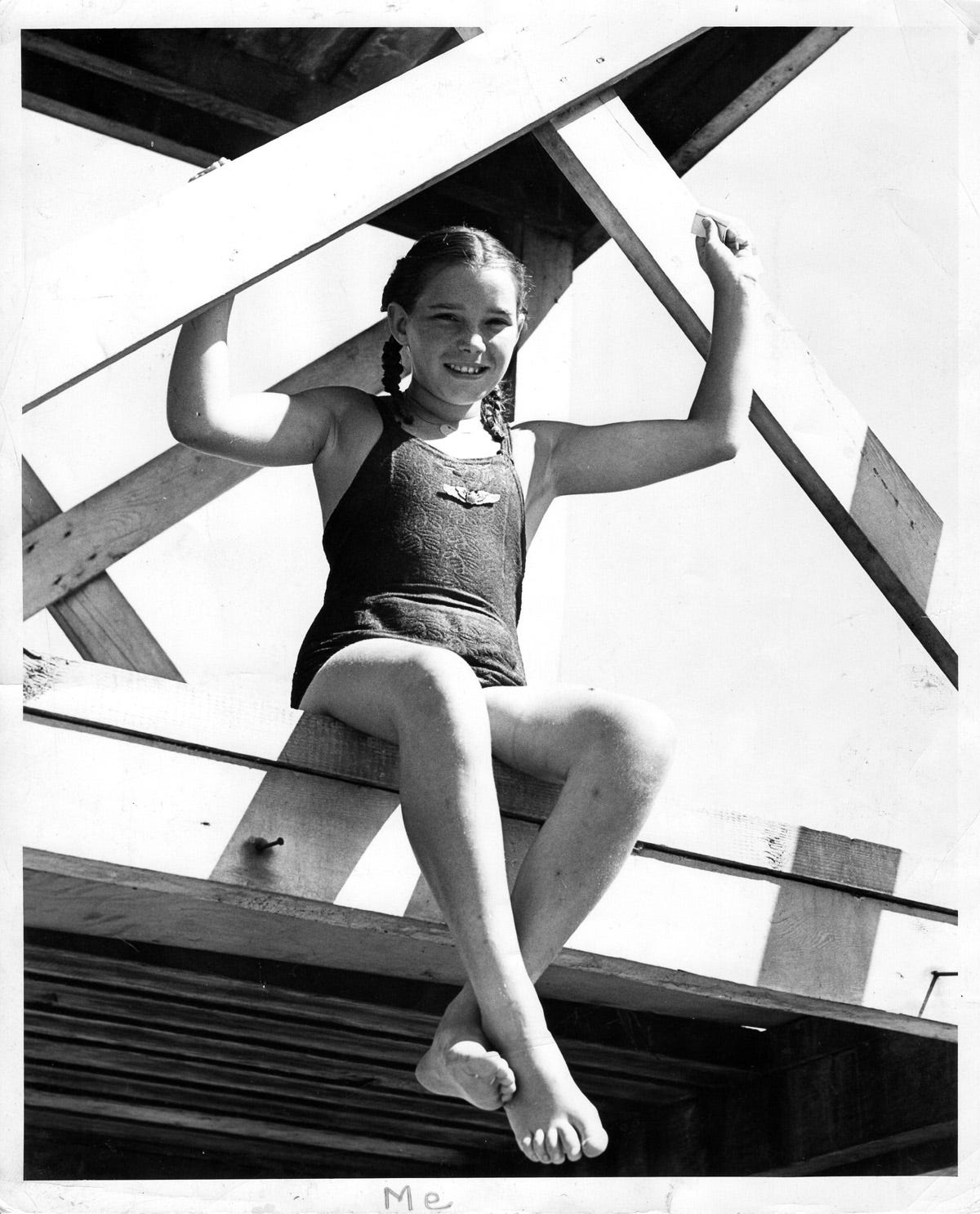

Erlyn Jensen was 12 years old when her brother, Major Don McCoy, sent her his wings and told her “Kiddo, if you wear these you’ll win your swim meet.” She did and she won. Major McCoy, a close friend of Colonel Jimmy Stewart, was killed leading the 445th Bomb group as command pilot on the ill-fated Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944. This is some audio from my 1999 interview with Erlyn, followed by an excerpt from a campaign speech from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Billy Wolfe, 18, was killed at Pfaffenheck, Germany on March 16, 1945. His older brother Hubert, ironically, was wounded elsewhere in Germany the day Billy was killed.

In 1993 I interviewed Billy’s sisters, twins Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten, whom I met at the first 712th Tank Battalion reunion I went to in 1987. As they went through the artifacts and letters that had been saved, they came upon a letter their father wrote, but didn’t send, after he learned of Billy’s death.

Maxine: This is Daddy's letter to Mom after Billy's death. He was in the Navy yard. He wrote it but he never sent it.

“Monday the 9th, 1:25 o'clock. Just got through my wash and will try to write you a few lines. I worked last night. Gigi and Phil are working today. We came to Richmond Friday, got there about 5 o'clock, stayed there until Saturday night p.m. o'clock, got home about 11 o'clock p.m., stopped at the post office, got the mail, got three letters from Hubert written March the 20th and 23rd and 27th of March. Poor child said he'd just written William” -- William, we called Billy William for fun -- “he never had but one letter from him since he has been in Germany. He wanted to know when we heard from him. Poor child, I just cannot hardly read the letters. I just think they will break my heart to hear him wondering about his brother Billy. But God knows it is not my fault, for the Democrats bring sorrow every time they get in, then they all try to creep back or hide behind a petticoat, or get where they never have to get into battle. But thank God I never helped to put him there. Well, I must close and get my supper and pack my lunch.”

Madeline: Oh, Daddy hated Roosevelt with a passion.

Above, the 712th Tank Battalion observing the death of President Roosevelt

Lieutenant Jim Flowers was the first of three members of the 712th Tank Battalion to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, after losing both legs in the battle for Hill 122 in Normandy. He spent three years in hospitals, and went on to become a prosthetics counselor for the Veterans Administration. While it offers little in the way of political analysis, I thought this would be a good way to end the Substack.

The first temporary prostheses I had were fabricated and fitted about nine months after I was initially wounded. I could figure it out to the day. Roosevelt died on April 12th, 1945. That was the day that I received my first temporary prosthesis. I was wounded in July, that's August, September, October, November, December, January, February, March, April...nine months to the day from the day they scooped me up on a piece of bloody French real estate until I put on my first temporary prosthesis.

I used to kiddingly say Roosevelt had lived a long time, and had a pretty full life. He had done a lot of good things, a lot of things with which I didn't agree, but I'm just one person. Somebody had probably called the president over at Warm Springs and said to him, "Jim Flowers is standing up and he's taking his first steps," and Roosevelt says, "I've heard it all. Nothing further that I care to hear." And he sat down and died.