The battle of Pfaffenheck

The story as told in a pair of letters

“Now this is when I was with the second platoon,” Bob Rossi said, glancing at some notes. “This is like March of ’45. I was on guard duty, the early hours of the morning, like daybreak, and I'm looking all around. We’re parked alongside the houses in this town, and these German soldiers are coming out of the woods with some girls. I guess they had partied overnight out in the woods, and I whispered down, “Everybody up, Krauts! Krauts!” With that, Martin, who was the gunner, he pushes me down, and he gets up and starts firing his tommy gun at them. And I could see them, all the Krauts and the girls start running in every different direction.”

So begins the prelude to the battle of Pfaffenheck, which would take place the following day, March 16. Rossi, a skinny kid of 19 from Jersey City, New Jersey, joined the battalion as a replacement a few months earlier. Martin was Otha Martin, a few years older, rugged, a rancher from Macalester, Oklahoma.

“Are you acquainted with Bob Rossi?” Otha said at the 1993 reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion. “He was a cannoneer [loader] that day. He was on guard, and I’m settin’ over on the cannoneer’s seat, kinda dozin’, and he just had his head up out of there. And he’s telling this several years ago when we had a reunion in Orlando, he tells me, “I’m lucky to be here.”

“I said, ‘How come?’

“He said, “I thought you was gonna kill me.’

“I said, ‘We never had no problem.’ Never did.

“‘Oh no,’ he said. ‘I don’t mean that.’ He said, ‘You jerked me out of that hatch up there and slammed me against that tank wall over there,’ and said, ‘I thought you were gonna kill me.’ Well, that tank wall is solid steel. Here’s what he was doing. He hadn’t been with us so long, but he was saying, ‘Heinies, Heinies.’ He saw ’em, but he wasn’t doing anything. Well, if they’s out there, I want to know. So I got him and I jerked him out of that hatch so I could get up there and I had a Thompson sub laying on the radio. I slammed him over here, and I got up in there, and that German was running; he had a long coat on, overcoat, and it was flopping. I started to work on him with that Thompson sub. Well, they’d always said if you could shoot a man anywhere, even in the hand, with a .45 it’d knock him down. That’s not true. It don’t stand up. I like to cut that one in two with .45 slugs and he finally did fall behind the tank, and Heyward hollered at me, ‘You got the sonofabitch!’ I buggered him up real bad, but he was dead. He was going to our tank. I don’t know if he intended to throw a grenade in there or what.” [Heyward was Sergeant Lloyd Heyward, a tank commander, who would be killed the next day.]

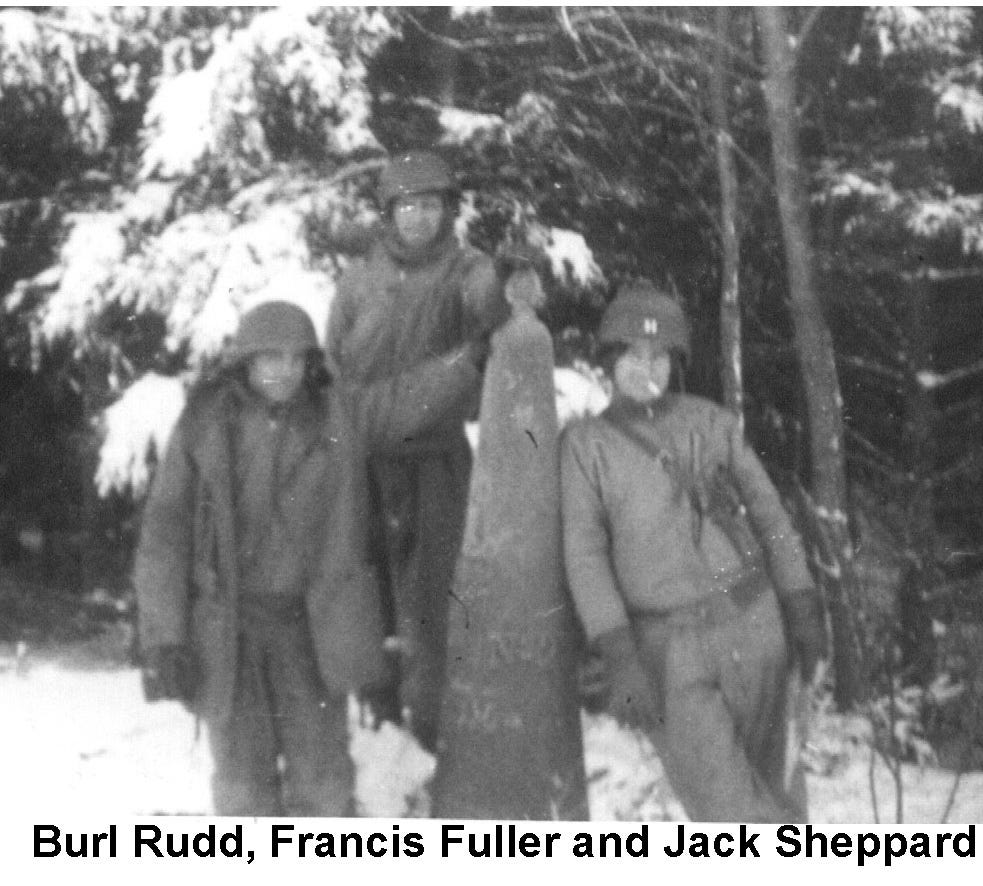

A pair of letters give a picture of the battle of Pfaffenheck. The first, written in 1986, was by Byrl Rudd, the platoon sergeant. He wrote it to Ray Griffin, the battalion association president, who asked him for an account of the battle after Billy Wolfe’s sisters, twins Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten, came to a reunion hoping to learn the circumstances of Billy’s death. The second letter was written in 1945 by Lieutenant Francis “Snuffy” Fuller in response to an inquiry from Billy’s mother that came down from pretty high up in the chain of command. But instead of writing to Billy’s mother, he wrote to Billy’s brother Hubert, two years his senior, who ironically was wounded the day Billy was killed, and was still in Europe.

Byrl Rudd’s letter

Having crossed the Moselle River, we spent most or all of the day clearing the high ground on the east bank. There were two companies of infantry with the second platoon of 712th, Company C (me) as support for either infantry company that might happen upon a machine gun nest. The Germans were backing up, supposedly, for a last stand at the Rhine River. We were giving them plenty of time because our left flank was lagging behind. From the sound of rifle fire, they were meeting more resistance than we were.

We moved slowly eastward all day. About sundown, we hit a spot of open terrain. This area was three to four miles square.

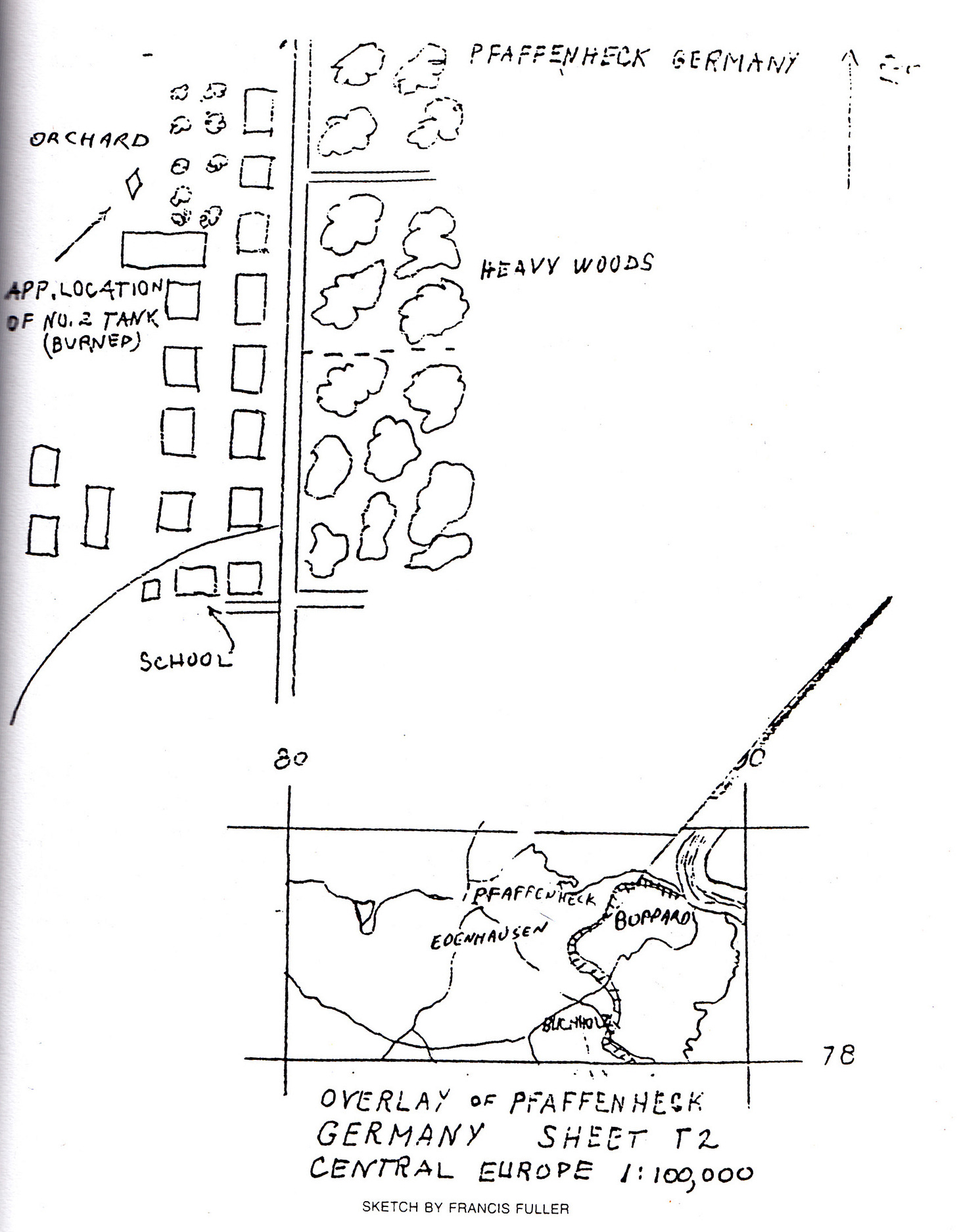

On our right flank, the trees extended to a small village approximately two miles ahead, so there was no problem to get there with cover all the way. This village was Edenhausen [actually it was Udenhausen]. A blacktop road ran north and south on the east of these two towns, and there was not one building on the east side of the road. There were tall pine trees 25 yards or less east of the road, and on our left flank buddies were still progressing too slow for me.

So here we are, mission accomplished. Two towns exposed to a blacktop road and miles of tall pine trees. I checked to see if all the tanks had a good field of fire and where the infantry outposts were. Nothing to worry about. The Germans have crossed the Rhine. WRONG!

Guards are out. The infantry is bedding down. Lieutenant Fuller looks out. I am looking out. He looks at me and I at him. Nothing is said. I feel like ducks on a pond, and so does he. Good houses to sleep in, but I am up making a noise. Guys are griping. Then, about 2 a.m., I hear people running near the rear of the town. I jump on my tank and listen. An infantry guard stops them. All are excited. They wake the officers and convince them of a horrible massacre in Pfaffenheck. Those boys, five or six of them, are the only survivors of the company. The infantry officers are furious and want to attack right away. Lieutenant Fuller and I have a powwow. We present our plan to avoid the road and attack five tanks abreast with the infantry on the back of the tanks across the open ground at full speed to the apple orchard. The time would be just at sunup. We are hoping that the big guns would be looking at the blacktop road. Plan accepted and carried out.

The apple orchard was full of SS troops. All had American guns. The second section soon cleared the orchard and three houses on the left side of the street for the infantry. I then had to go forward to get a field of fire down the street. It curved or made a couple of angles. The infantry was taking a beating, which I thought was coming from the right side of the street.

There was no big stuff up to now. At the first intersection, I saw Lieutenant Fuller moving and firing at the second intersection. I saw him stop. We were both firing across the blacktop road into the tall pines that were thick with Germans. We had them running, I thought.

Lieutenant Fuller’s tank was hit by an antitank gun. He got out and made it to the buildings. About the time he got there and looked back, Lloyd Hayward came out of the top hatch. One of his legs was limp. Lieutenant Fuller started after him. Machine gun fire stopped him.

The fifth tank was not able to fire in that direction. I jumped out to go get Lieutenant Fuller while my gunner kept them pinned down across the road. I got Lieutenant Fuller to go back down the street to find a medic. I found Russell Harris, the tank commander, was slowly dying from a bullet that had just grazed the top of his head while he was in the orchard. The medic told me his life might be saved if we could get him to a hospital within four hours. The boys had got him out of the tank. He seemed to be in no pain. They tried to get to him with a jeep, but the SS drove them back. They tried later with a halftrack, and the SS drove them back again. While I was there, I learned that the driver of the No. 2 tank had been killed about 50 yards after leaving the orchard. This man was Jack Mantell. Those SS troops were tough. [Actually, Mantell was the loader in Lieutenant Fuller’s tank.]

Being under strength going into this action, the infantry company was very slim in men able for combat. I had seen their officer killed. Upon getting back to my tank, I found the roof of the house that was protecting me to be on fire. Lots of the SS were moving around in the pines. I decided to try the antitank gun again. He was still there, and he knew where I was. Time to try something else.

The field artillery had been firing all day, but their shells were going too far to help me. I went to find an infantry non-commissioned officer who knew where the phones were. He would not call the field artillery, so I called someone and got to talk to the field artillery fairly soon. He finally agreed to bracket one gun. The first shell hit between me and the No. 5 tank. I told him to raise it 200 feet. Since the two tanks were the only men near the road, he agreed, with a promise to pull it down if the SS tried to come back into town.

The field artillery went on until an hour or more after dark. The SS had quit shooting at us. They were still milling around in the trees across the road.

After doing my job on the ground, I got back in the tank. The roof had fallen in on the house protecting me from at least one antitank gun. While trying to get my nerve up to try him one more time, I noticed that the one rifleman to my right was not an infantry man but was a tanker. This man was Aaron C. Brown, who had gotten out of No. 5 tank and had picked up a rifle and came up where my tank was. Standing at the corner of the house, he picked off several SS men when they moved from one tree to another.

After more than an hour of field artillery fire, I got nervy and decided to try to get one more shot at that antitank gun. He knew what I would do and was waiting. If I had pulled out one more inch, he would have gotten my gun shield. Then I tried backing up again, but the space between the two houses was too wide. He would have gotten two shots at me. There were probably two of them, anyway.

After dark, I got my tank backed up to the disabled crews. I organized three tank crews ready to go full-strength. Then with the few infantry boys left, we set up our defense for the night.

I called the field artillery again. I told them our position and said that I would tell them if the SS tried to reenter the town to shell the east half of the town.

We had accomplished our mission. However, at dark there were a lot more men on the other side of the road than there were on our side, so every man pulled guard all night long. We got no information or instructions from anyone all day or that night. The men finished what they could do by about 2 a.m. (too late for Harris).

The next morning, the first thing we saw move was 12 or 15 American tanks coming down the blacktop road from Edenhausen toward us like they were on a pleasure cruise going to Koblenz. When they stopped, we found that everything movable in the woods was gone. There had been two antitank guns where Lieutenant Fuller was firing when he was hit. One was knocked out, I’m sure by Lieutenant Fuller. The other had been towed away.

That morning we were informed that 3,200 SS troops were in the woods when we attacked. It scares me to think what might have been had we attacked down the blacktop road that morning.

I’m almost sure about the fourth boy killed in Pfaffenheck, but I will check with Wes Harrell. He was the driver of Snuffy’s tank. Three boys were wounded, but I don’t remember who they were, either.

Lieutenant Fuller’s letter

“To Pfc. Hubert L. Wolfe Jr., Company M, 310 Infantry, APO 78, 14 July, 1945

“I hardly know how to start this letter, as you don’t even know who I am. Anyway, Lieutenant Seeley, the adjutant of our battalion, received a letter from you asking the facts about your brother, Billy Wolfe. As I was his platoon leader and was there when he was killed, he has asked me to try to give you the information you requested.

“Captain Sheppard has already written your mother, but perhaps he has not told her exactly how he died. But I am trusting that since you are a soldier, I can tell you the true facts, and then perhaps you can tell your folks what you think they ought to know.

“To start off, our battalion has been attached to the 90th Infantry Division since July 3rd, 1944, which as you probably know is in the Third Army. My platoon, the second platoon of C Company, 712th Tank Battalion, was attached to the Second Battalion of the 357th Infantry Regiment.

“Your brother joined my platoon on the 4th of March while we were driving to the Rhine River, following up the 11th Armored Division. We drove to a town called Mayen, and then changed direction and started driving to the Moselle for the second time.

“On the evening of March 14, we crossed the Moselle and found that the infantry that had preceded us had gotten into a jam and lost over half of their men and gotten cut off, so we were called upon to rescue them.

“We succeeded in reaching the town where they were, and cleared it okay, and stayed there the rest of the day, and stayed there the night of the 15th. Then, on the morning of the 16th, we were told to attack the town of Pfaffenheck, which was about 2,000 yards north of where we were. The TDs [tank destroyers] started into the town first, but as they rolled over the crest of a hill, the lead tank destroyer was knocked out by an antitank gun. They withdrew, and succeeded in knocking out the gun and another.

“We were then ordered to try to enter the town, and by going down a draw, I managed to get into the east side of the town.

“Your brother was in the No. 2 tank, which was commanded by Sergeant Hayward, with Johnny Clingerman as gunner, William Harrell as driver, Koon Moy as bow gunner, and your brother as loader.

“As I said, all of the tanks got into the town okay except No. 3, which encountered a 40-millimeter AA (anti-aircraft) gun, which killed the tank commander.

“We took all but three houses, when the infantry got stopped by firing from the woods east of the town. In order to knock out the gun that was holding up the infantry, the tanks started to move out to get a firing position. I sent the second section along the back of the houses, while I took the first section into an orchard. My tank was in the lead, and the tank your brother was in was on my left flank, slightly behind.

“Just after we had passed an opening between two houses, my loader told me No. 2 tank had been hit. I looked over, and the men were piling out, and the tank was blazing. The shot had went through the right sponson, puncturing the gas tank.

“I didn’t know then how many men had gotten out, so I tried to get my tank into position to rescue the men, but as I moved into position, my tank received a direct hit through the gun shield, killing my loader. Fortunately for the rest of us, my driver was able to move the tank before the Heinies could fire again.

“After giving Clingerman first aid and getting the rest of the boys calmed down, I took my gunner with me and we crawled out to where Sergeant Hayward lay wounded. I found that he would have to have a stretcher to be moved. I went back to get the medics, and then I learned from the rest of the crew that your brother never got out of the tank. As the tank was burning all this time, we could not get near it. I don’t know if you have ever seen one of our tanks burn, but when 180 gallons of gas start burning, and ammunition starts to explode, the best thing to do is keep away.

“When I got the medics back out to Sergeant Hayward, I found he had been killed by a sniper. The other section of tanks finally took care of the Heinies, and we secured the town.

“Your brother’s tank continued to burn all that night, but in the morning we were able to go out to investigate. We determined that your brother had been killed instantly, as the shell had hit right above his seat. There was nothing visible but a few remnants of bones that were so badly burned that if they had been touched, they would have turned to ashes.

“As for personal effects, you could not recognize anything because the intense heat and the exploding ammunition had fused most of the metal parts together.

“The accident was reported to the GRO of the 357th, and as we moved on to the Rhine the next day, I didn’t think anything more about it until two weeks ago when I received a letter from the Third Army asking for information. I sincerely trust that by this time they have everything straightened out. If you ever get into the neighborhood of that town, the tank may still be there. The town of Pfaffenheck is about 13 miles south of Koblenz on the main autobahn that runs straight down that peninsula formed by the Rhine and the upper Moselle.

“Maybe I have told you more than I ought to, but I really would like to help you in any way that I can. Your brother was very well liked by all the rest of the crew, but he was so doggone quiet that we hardly ever knew he was around. Of the other members of his crew, William Harrell is still with me, as is Koon Moy. Clingerman lost his eye and had his legs filled with shrapnel and is now back in the States. That was the worst day I had in combat. I lost three tanks, had four men killed and three wounded. But that is the way things went. It might be interesting to you that in the town there were seven antitank guns, one 40-millimeter antiaircraft gun, plus plenty of determined SS troops. We counted 92 dead Germans and had 23 prisoners.

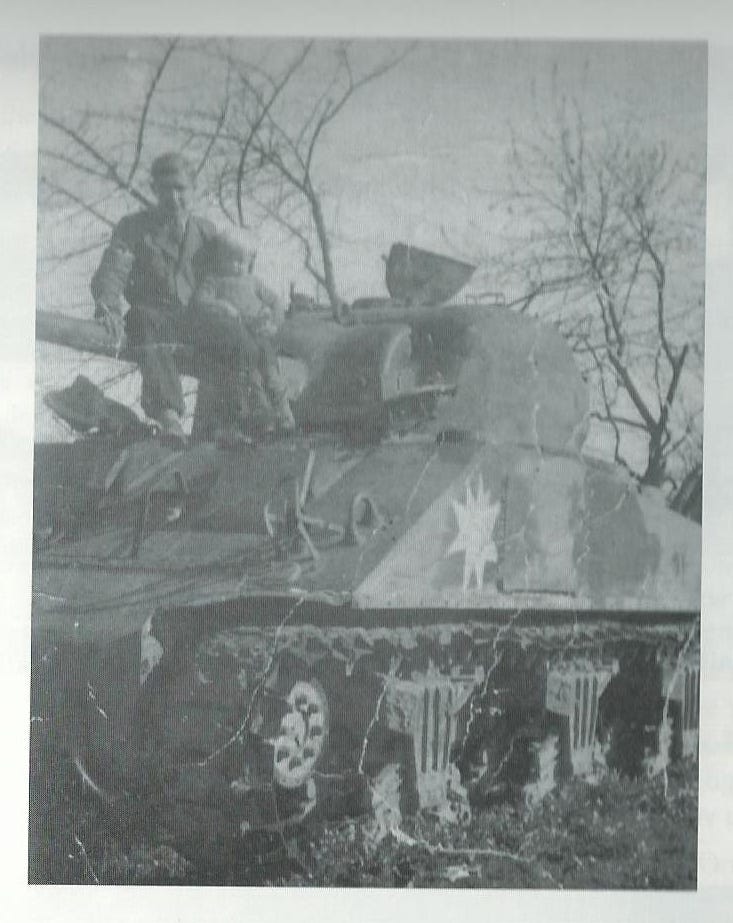

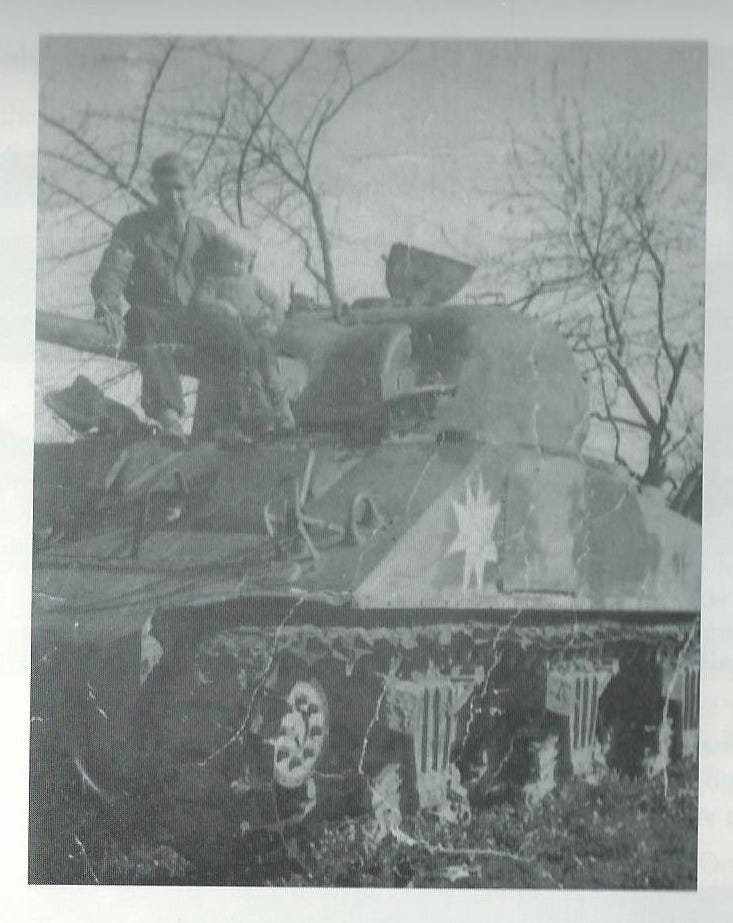

“I am enclosing a snap one of the boys took which has your brother on it. I will also try to draw a sketch of the town, so if you ever get there you can find the place.

“Incidentally, you will have to use your judgment as to how much of this story you want to pass on to your mother.

“Don’t forget, if I can be of any further help to you, I will be more than glad to hear from you at any time. There is no use in trying to tell you how sorry I feel, because you have been through the same things yourself, so I’ll just say so long and good luck.

“—Francis A. Fuller, First Lieutenant”