Smoot Schmid. I love corroboration, when even a small detail in one interview matches a detail in either another interview or a document. Now there’s a name you don’t hear very often. I recently heard from Steve Wawrzonek, the grandson of Lieutenant Jim Flowers. A couple of years ago I sent Steve a set of CDs with the audio of my interviews with several members of Jim’s platoon who survived the ambush in which all four Jim’s tanks were knocked out, with three of them going up in flames, in Normandy.

A couple of weeks ago Steve messaged me on Facebook to ask if I had a copy of “The Armored Fist” he could purchase. The Armored Fist is the only one of my books that I didn’t publish myself. It was published in England by Fonthill Media and it either sold out or the remainder of the print run was sold to Casemate, but either way I only have one copy. It still is available for Kindle.

But I told Steve I was glad to hear from him because I recently came across a folder in my meticulously organized archives that contained ten short audio clips, which I hadn’t transcribed, with brief interview/conversations with Steve’s grandmother, Jeanette Flowers, and in some of them, also with Jim.

A little background. The shell that penetrated Jim Flowers’ Sherman tank in Normandy tore off his right forefoot as he stood in the turret. As his gunner, Jim Rothschadl, scoured the edge of the field for signs of a muzzle blast, a second shell struck and the tank burst into flames. Flowers helped Rothschadl out of the tank and dropped down to the ground himself, both tankers badly burned. That night the two men lay in no man’s land. The next day, a fragment from an artillery shell tore off Flowers’ other foot. He and Rothschadl spent another night in the field and were rescued by a patrol from the 357th Infantry Regiment the following morning, July 12, 1944.

In 1993 when I did my somewhat formal interview with Jim at the battalion mini-reunion at the Days Inn in Bradenton, Florida, Jeanette sat in for much of the interview. In describing the moment the second shell struck the tank, Jim delivered his iconic line, “I’m now standing in the middle of hell, with all these flames shooting up around me.” He said he then fell back into the turret basket, and that it might have been his assistant driver, Ed Dzienis, trying to climb over him to get out of the tank. Jeanette said, “You told them to abandon tank.” Jim then said, “Yes, but don’t drag me down into this barbecue pit.”

Jim would go on to spend three years in hospitals, which is where Smoot Schmid comes in. Jim and Jeanette lived in Dallas, and Jeanette had not seen Jim since he went overseas. After a year and a half in the hospitals, he wound up for a short time at Love Field in Dallas while he was being transferred from McCloskey General Hospital to Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Jeanette got a phone call telling her if she hurried, she could see her husband while he was at Love Field. There was only one problem. Jim’s father and mother had taken Jim and Jeanette’s daughter to the movies, and the manager of the theater refused to interrupt the film to get them.

Oh yes you will, or words to that effect, Jeanette told the manager, or else she would call Smoot Schmid.

I was like Smoot who, or words to that effect. Jeanette said he was the sheriff of Dallas and that he was a personal friend. At the mention of his name the theater manager relented.

When I asked who Smoot Schmid was, Jim said he was about 6 foot 6 and 280 pounds and undoubtedly was an imposing figure. I also learned when I looked him up on the Internet that he was a legendary Texas lawman. But first the corroboration

. From the Texas History Notebook blog:

Schmid was unusually tall for his day. He stood over 6 feet 5 inches in height and acquired his nickname “Smoot” while in school. He didn’t mind it. One of his earliest jobs was to own and operate a bicycle shop on Commerce Street downtown. He quickly expanded into motorcycles, becoming an expert operator of each.

When he was about thirty-five years old, he won an election for County Sheriff of Dallas in 1932 and became Dallas County’s twenty-eighth sheriff, succeeding Hal Hood. This decade was one that was marked by gangsters and bank robbers who regularly made headlines in the daily newspapers. Most Americans were dealing in some way with the effects of the Great Depression and also with the enactment and repeal of Prohibition. In Texas, there was the menace of Barrow Gang: Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker, Floyd and Ray Hamilton and others.

Also from Texas History Notebook:

The Barrow Gang continued to elude authorities and stay on the move, passing in and out of the Dallas County and North Texas area. Schmid got word that Clyde and Bonnie were likely coming to town in November 1933 for a family reunion and also for Clyde’s mother’s birthday in Sowers, Texas. Sowers never had more than about 120 residents and now it is part of Irving, roughly near the intersection of Esters Road and Highway 183. Only the cemetery still exists. In a scene that foreshadowed the final ambush seven months later, Sheriff Schmid and some deputies including Ted Hinton and Bob Alcorn set up an ambush. As Clyde drove through, he slowed down and the lawmen fired on the car. Both Clyde and Bonnie were wounded and the car was badly damaged, but they still got away. The duo abandoned the car and stole another one. Hinton and Alcorn would be involved in the final ambush in Louisiana led by Frank Hamer. Schmid would later take part in the capture of Ray Hamilton in a Fort Worth rail yard.

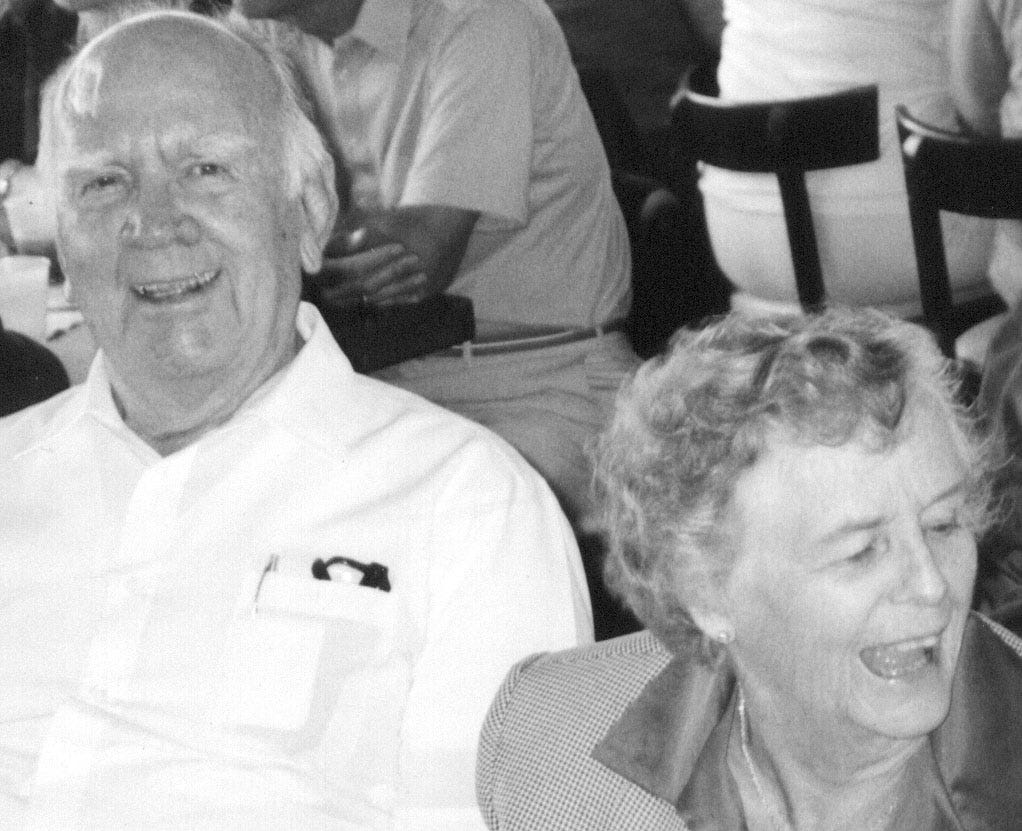

Jim and Jeanette flowers: