If you were me, you probably would have listened to some of the stories you’ve recorded dozens of times: first when you heard it in the hospitality room or interview or conversation, then when you transcribed it, and when you edited the transcription, again when you added the audio to a CD or flash drive, and multiple times when you played the audio at air shows and vendor events, and sometimes just for the heck of it while driving. And every so often, on the three dozen and oneth time listening to a story, you’ll hear a word or a name or a detail you hadn’t noticed before that alters the trajectory of another story you’ve also heard many times.

Such was the case a few days ago as I was listening to a kind of innocuous but entertaining story about flat feet, told by Sergeant Ed “Smokey” Stuever. You can listen to the story and read the transcript at the link, but for now I’ll paraphrase it:

Before going overseas, the men had a physical, during which the medical officer told Smokey he had the flattest feet he ever saw, that he was a medical officer in World War I, and that Smokey wasn’t fit to be in this man’s army. He handed Smokey a piece of paper and told him to bring it to his commanding officer, so he could be reassigned to carry bedpans in a hospital. Smokey was, to say the least, not very pleased, and he went barging into the day room to give the paper to Sergeant Bennett. Bennett says words to the effect of what the hell’s the matter with you, Smokey, now go outside and knock and enter like you’re supposed to. Captain Davis hears the commotion and comes out of his office. Smokey says something about bedpans, and Davis tells him he was just put in for sergeant, and asks Sergeant Bennett if he posted that yet. Davis tears up the paper and drops it in the wastebasket. Smokey fishes the pieces out and says he wants to keep it so that if he ever sees the medical officer again, he can run him over with his tank.

As I was listening to this during a vendor event in Manchester, Connecticut, last weekend, I did a doubletake, and then a tripletake, upon hearing the name Captain Davis. It suddenly occurred to me that this was probably Major Davis, the battalion executive officer, or Baxter Davis, as he was usually referred to.

Welcome to the rabbit hole.

If — not if but when — they make a movie about the 712th Tank Battalion, Major Davis, who wouldn’t see a day of combat with the battalion, would play a part in a key event in its colorful history.

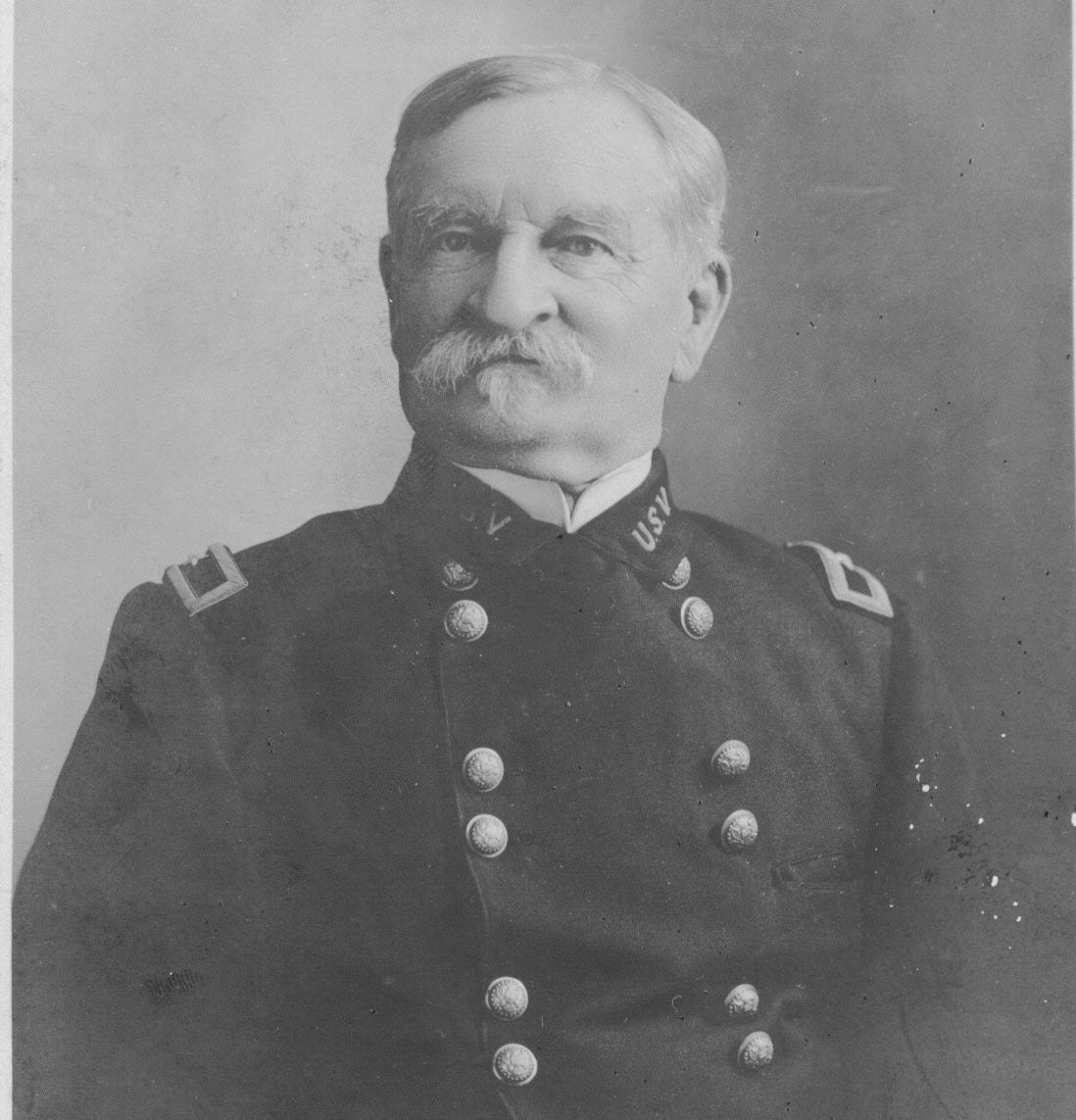

Davis was the Number 2 in the chain of command. The battalion’s original commanding officer, Colonel Whitside Miller, was so rigid and incompetent that he had the officers on the verge of mutiny. And in England a letter-writing campaign by the officers succeeded in getting him replaced. Baxter Davis was also transferred out, according to some of the officers, to allay any concern that he was trying to undermine Miller in order to be promoted himself. So Smokey’s story provided me — assuming Captain Davis was indeed Major Baxter Davis, which I believe he was — and whoever makes the movie with at least some insight into his character. I previously knew nothing about him other than a brief discussion at a reunion about whether he was still alive (he wasn’t) and an account of a card party involving his wife.

Some of Colonel Whitside’s signs of poor leadership might not rise on their own to the level of mutiny-inspiring. He yelled at Sergeant Dan Diel for being at a bar, and then went in and sat at the bar and ordered a drink. He ordered Smokey to make sure all the tanks in his platoon were cleaned out after an exercise, and Smokey had to report the exhausted crews of two tanks, knowing the men would hate him for it. He was seen to be drunk prior to boarding the SS Exchequer to cross the Atlantic. He ordered Forrest Dixon, a maintenance officer, to put blackout drive lights on the tanks, when blackout drive lights were for general purpose vehicles, like trucks, and not for tanks, and threatened to court-martial him when he said ordnance told him it couldn’t be done.

But the most egregious thing he did was in front of the whole battalion, he asked his executive officer, Baxter Davis, to do something, and then ordered Davis to doubletime.

“Do you remember Colonel Miller, the [original] battalion commander?” I asked Howard “Olie” Olsen, one of 14 sergeants who received battlefield promotions to lieutenant, when I interviewed him at his home in South Bend, Indiana in 1993.

“Yeah,” he said. “We were in England, and we were supposed to make a night problem — I mean, pull up at night and get in position. And right behind my tank was Colonel Miller, and who was the major?”

“Baxter Davis,” I said, having heard various iterations of the story, but this was my first eyewitness, or earwitness, as it were.

“Yes,” Olie said. “The colonel told him to go do something. And he started to walk away, and he said, ‘You run!’ That’s when they started filing charges against Colonel Miller. And they got rid of him. I heard they busted him to a captain and shipped him back to the States. He was a West Point man. Of course, we don’t have a lot of dealings with the colonel unless you’re in the battalion headquarters. But he was right behind my tank. I heard the whole thing. He told him, ‘You’d better doubletime.’ You’re not supposed to do that. If you’re going to bawl out another officer, do it in private, not out in the open where everybody can hear you.”

Davis “was made to look like a horse’s ass. That was a terrible thing to do,” Bob Hagerty, another sergeant who received a battlefield commission, said.

“What were the circumstances?” I asked. “Because I don’t have a military background, often I’ll hear something three or four times before I realize its significance, like this Baxter Davis having been ordered to doubletime. The first time it didn’t seem like anything out of the ordinary. But a couple of people have said it was such a terrible thing.”

“I mean, to show him up in front of everybody,” Bob said. “An officer doesn’t do that to a fellow officer, or as a commander you don’t do that to your second in command, because he’s holding him up to ridicule. I mean, how is that man going to function the next time he’s commanding somebody to do something. I remember Kedrovsky [Colonel Vladimir Kedrovsky, the battalion’s third and final commanding officer] saying that to me. He would come up once in a while when we were in combat, or maybe if you had a little temporary period where you were out of contact, and might have a day or two to wash clothes or something, and he came up on one of those occasions. I think I’d already been commissioned in February, the war was nearly over. He came up maybe sometime in March or April, and we were talking, and the other guys were talking, there was a free give and take. I mean, it wasn’t real strict. You have an officer, you don’t talk unless I say talk, there was none of that. It was all very casual. But anyway, he’s up there visiting, and we were having this conversation, and he said, ‘Lieutenant, come over here, I want to speak to you.’

“I go over where he was kind of separated from the men, and he was commenting on the way the men were dressed. He said it’s fine to be friends, but the time’s going to come when they’re going to react instantly to what you want them to do, and you’ve created a relationship that doesn’t produce that instant reaction. You could regret that. I want you to think about that.

“Because before I was commissioned, some guys called me Bob of course, like Morse [Johnson] or Sam MacFarland, but an awful lot of guys called me Hag. The supply sergeant at the time was Charlie Vinson, then he later became first sergeant, and he always said Hag this and Hag that, which was all right, I didn’t mind that. But Kedrovsky didn’t think that was very smart of me.”

The Bridge Game

When Whitside Miller was relieved of his command, Major Davis was transferred out as well. The consensus was that this was to alley concerns that Davis was undermining Colonel Whitside in order to be promoted himself. Vladimir Kedrovsky, the third in command, was not transferred and became the battalion executive officer, a position he held until Colonel George Randolph, who replaced Colonel Whitside, was killed in the Battle of the Bulge. But going back to the story that launched this Substack, Captain Davis confides in Smokey that he has asked for a transfer to the Air Corps, so that might have been the reason he was transferred.

Which brings me to the 1995 Florida mini-reunion of the battalion and the infamous card party.

“Did anybody ever hear from Baxter Davis, or is he dead?” Jim Cary, who was a company commander in the battalion, asked.

“Baxter died,” Clegg “Doc” Caffery, one of the officers in Headquarters Company, said.

“You know, that’s when Norma [Cary’s wife, who was also at the table] got sandbagged,” Cary said. “She was having a card party, a bridge party, and in walks Amanda Kedrovsky, and was Baxter’s wife there? And they started arguing back and forth right in front of everybody about Colonel Miller, he was gonna lead them to death, and poor Norma, she’s caught in the middle of this. She didn’t know what was going on.”

“If it hadn’t been for [Jim’s] mother,” Norma said, “who was visiting, god only knows what would have happened. She was an elderly — not elderly at the time, she was probably 40 and I was 20, 19 or 20 — but she said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t open your mouth and say what went on here to anybody, and don’t even tell Jim.’ So when they called Jim in, he didn’t know what was going on.”

“What was going on?” I asked.

“These two wives, they both had husbands that were vying for control of the battalion,” Norma said. “They were both majors, and both of them wanted their husbands to take over.”

“They started after each other at that party,” Jim said, “shouting at each other that Colonel Miller was gonna lead the tank battalion to disaster and everybody would get killed, and so the first thing I know I get called on the carpet. ‘What’s going on at your house?’

“I said, ‘I don’t know.’

“Miller said he had heard some kind of plot was hatched at my house. And I said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

“So I was called in,” Norma said, “and they called Jack Dougherty’s wife, Miriam, was playing bridge, she was there too. So he called Miriam, and he called me, and poor Miriam was shaking in her boots, and I said, ‘Miriam, don’t worry. We’re not in the Army. We don’t have to talk.’ And we got in their office, and he said, ‘And what do you know about this?’

“I said, ‘I’m not talking to you. I’m not in the Army.’”

“So is that what the two women said?” I asked. “That Miller was going to lead them to death?”

“To disaster, that’s the way I got the story,” Jim Cary said. “I wasn’t there.”

“Evidently, one of them, and I won’t swear to which one because I don’t really remember, I think it was Gladys…” Norma said.

“Gladys is who?” I asked.

“Baxter Davis’ wife,” Jim said.

“She wanted to start a petition, and have everybody sign it, to keep Miller from going overseas,” Norma said. “That’s what it was all about, really. And I don’t remember enough about what happened. Pat and Gladys were at each other’s throats.”

“Pat was who” I asked.

“Kedrovsky’s wife,” Doc Caffery said.

“Pat and Amanda are the same person,” Jim said. “We always called her Pat. We didn’t know she had the name Amanda until many years later.”

The good thing about rabbit holes is there’s usually a rabbit at the bottom. Instead of carrying bedpans, Smokey and his crew changed tires, installed engines and retrieved damaged tanks all the way from Normandy to Czechoslovakia. Whitside Miller was replaced by an officer who was loved and respected by the men under his command. And according to a lovingly written obituary by his daughter Janet Kern Simkins, Colonel Whitside “joined A.A.” in 1973. “Later, living in San Diego, he found real serenity in the program. His family was very proud of him for turning his life around. It took a strong and determined person to beat that illness. The last 20 years of his life were dedicated to helping hundreds of people maintain sobriety, with an unconditional commitment for everyone in A.A.”

Love it! Aaron is quite a writter!