“Did he tell you about the turning plow?”

Jim Flowers received one of three Distinguished Service Crosses awarded to members of the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served in World War 2. The others were Private Ted Davis and Lieutenant Colonel George Randolph, the latter posthumously.

At the 1987 battalion reunion, the first one I attended, I was in the hospitality room when Flowers arrived. As he entered the room, I overheard Byrl Rudd, who’d been a sergeant and tank commander, tell someone that he cried when he heard Flowers was alive.

The battalion’s first day in combat was July 3, 1944. Exactly one week later, Lieutenant Flowers led four tanks of the first platoon of C Company to the aid of the 358th Battalion of the 90th Infantry Division. The battalion was surrounded by German paratroopers on the plateau atop Hill 122 in Normandy. After breaking through the German lines and reaching the embattled infantry, Flowers and the battalion’s commanding officer, Colonel Jacob Bealke, decided that Flowers would lead the battalion’s K Company down the hill, and the rest of the battalion would follow.

It didn’t quite work out like that. The infantry company took heavy casualties and dug in at a blacktop road at the base of the hill. Flowers’ tanks crossed the road and continued going, unaware that they had little or no infantry protection.

One of the four tanks bogged down in the mud and was immobile. It was then struck by a shell fired from a concealed antitank gun in a corner of the field. The tank’s gunner lost an eye, the driver was killed outside of the tank, and Captain Jack Sheppard, the company commander who was filling in as a tank commander, was slightly wounded in the face.

The three remaining tanks were knocked out, one after another; in all the platoon suffered nine of 20 crew members killed, and several men wounded and/or captured. All three tanks went up in flames. The armor piercing shell that penetrated Flowers’ tank tore off his right forefoot. Both he and his gunner, Jim Rothschadl, were badly burned.

It was late in the afternoon when the tragedy took place. Flowers and Rothschadl lay in no man’s land while the weeklong battle for the area known as the Foret de Mont Castre seesawed back and forth. That evening a German patrol passed through and its medic bandaged Flowers’ badly burned fingers. The next morning American artillery rained down on the field in which Flowers, Rothschadl and a mortally wounded infantryman lay. A shell fragment severed Flowers’ other foot. The next morning an American patrol led by Lieutenant Claude Lovett came upon the scene. The infantry man had passed away but Flowers, just barely, was still alive, as was Rothschadl.

In the meantime, despite the terrible loss sustained by the platoon, its action was considered to have helped turn the tide in the weeklong battle. The 90th Infantry Division recommended Flowers for the Medal of Honor, and he was awarded the DSC.

From his hospital bed, Flowers wrote an account of the events in support of the Medal of Honor recommendation. A copy of it was given to me by his gunner, Jim Rothschadl.

Saturday, 19 January, 1946. Colonel Robert L. Bacon, Headquarters, 8th Service Command, Dallas, Texas.

Dear Colonel Bacon,

In compliance with your request, I submit for your information an account of the action in which I was wounded. It was on 10 July, 1944, while I was attached to the First Battalion, 359th Infantry, that I was told that the Third Battalion, 358th Infantry, was surrounded by a strong force of SS paratroopers* in the Foret de Mont Castre.

This information was brought to me by Lt. Harlo J. Sheppard, who was motor maintenance officer of Company C, 712th Tank Battalion.** Since the First Battalion, 359th Infantry, was on its objective and I was eager to engage the paratroopers, I went immediately to Captain Leroy Pond, C.O. of the First Battalion, to ask permission to go to the assistance of the Third Battalion, 358th Infantry. He gave permission but requested that I return to his command as soon as possible.

I went back to my tanks and called the tank commanders together, giving them the information I had received, and told them of my plan to reach the encircled infantry battalion.

After instructing the platoon sergeant, Staff Sergeant Abraham I. Taylor, to meet me at a designated place on Hill 122, I got in a quarter-ton truck with Lieutenant Sheppard and went to the Foret de Mont Castre to make a personal reconaissance of the situation.

When Staff Sergeant Taylor arrived on Hill 122 with the tanks, I called the tank commanders together to give them orders for breaking through the enemy line. Lieutenant Sheppard volunteered to command one of the tanks in the attack. I placed him in the No. 4 tank. I then got in my tank and led the assault upon the enemy position.

Encountering only small arms fire, I had no difficulty in destroying the enemy and reaching the position of the Third Battalion, 358th Infantry. Upon my arrival at the Third Battalion O.P., I reported to Lieutenant Colonel Jacob W. Bealke, C.O. of the Third Battalion. Colonel Bealke and I immediately made plans for launching an attack upon the remainder of the paratroop forces in the Foret de Mont Castre.

From the interrogation of eight captives, we learned that our enemy was the 15th Regiment of the Fifth SS Paratroop Division. This regiment had been in the line only two days.

In the assault wave were one company of infantry and the first platoon, Company C, 712th Tank Battalion. My tanks were deployed in line, with riflemen in line between the tanks. Enemy resistance was fierce, and the thick underbrush made the infantry advance extremely hazardous and slow. My four tanks were soon almost alone in the attack. We overran many enemy machine gun positions, killing the crews.

On reaching the hard surface road at the edge of the Foret de Mont Castre, which was the objective, I made a rapid estimate of the situation and saw that it was possible to continue the attack and assault the enemy positions in a hedgerow approximately 800 yards to my front.

I gave the order over the radio to continue the attack and destroy the enemy. Leading my platoon across the road and into the open field, we were successful in destroying many machine gun nests and in killing large numbers of paratroopers. Enemy resistance was broken by our vicious assault.

Continuing the assault to the enemy positions in the hedgerow, we quickly neutralized their firepower. During the entire action in the open field, we were subjected to terrific bombardment from artillery and mortars.

Three tanks arrived at the hedgerow without casualties. The tank commanded by Lieutenant Sheppard became stuck in a marsh almost immediately after crossing the hard surface road. Lieutenant Sheppard reported this to me at once, and I told him to give supporting fire. From that position, Lieutenant Sheppard was able to support my advance by firing ahead of me. He did this despite the artillery and mortar fire falling all around him. His turret hatch covers were open all the time, as were those in the other three tanks. The purpose of open turrets was to enable the tank commanders to better observe and to fire the machine guns mounted on top of the turrets.

Lieutenant Sheppard did an excellent job commanding the tank and directing its fire. The fight from the tanks at the hedgerow was devastating on the paratroopers. I did not continue the attack from this position because I didn’t have adequate infantry support, and I estimated my position to be about on line with the Third Battalion, 359th Infantry, on my right flank. I did not know exactly where the Third Battalion, 359th Infantry, was located, and I did not want to advance too far and risk getting cut off from friendly forces.

All was in our favor in this position. I was waiting for Colonel Bealke to bring his infantry up to occupy the excellent positions I had taken.

Then, suddenly, an anti-tank gun opened fire on me from my left front. It fired only one round at my tank, which bounced off the left sponson.

Immediately, I transmitted to the other tanks to search for A.T. guns. While I was searching for the gun that had fired at me, an A.T. gun on my right flank opened fire on my tank. The first round pierced the tank through the right sponson and came through a 75-millimeter ammunition rack, igniting the powder.

Because of the intense heat and fire, I gave the order to abandon tank. I assisted my gunner, Corporal Rothschadl, in getting out. I went under the 75-millimeter gun to get my loader, Pfc. Dzienis, but was unable to locate his body. The tank was a huge ball of fire, with flames leaping out the turret several feet into the air.

Subconsciously, I knew that I had been hit. Not until I had crawled to the top of the turret and jumped to the ground, did I realize that my right foot was gone.

My first concern was for the safety of my crew. I called for my driver, T-4 Gary. He came at once and said neither he nor the bow gunner, Pfc. Kiballa, were wounded.

With assistance from Gary, I was able to get over the hedgerow to my right flank. It was necessary to get out of the field where the tank was burning because of the great danger of exploding gasoline.

While my crew and I were abandoning our burning tank and getting over the hedgerow, the enemy A.T. guns destroyed the remaining tanks.

Using my belt as a tourniquet around my right leg, I was able to stop the spurting of blood from the severed artery. The German paratroops seized this opportunity to attack us. Despite severe burns to my hands and face and the loss of my right foot, I was fortunately able to organize a defense among the few surviving tankmen and infantrymen. We fought the paratroops with any weapon in our possession. Tommy guns, rifles, carbines, knives and fists were used to kill them. When my own tommy gun was out of ammunition, I had to use a knife on one paratrooper who was choking a wounded infantryman.

Most of my small force was killed or wounded in a short time. Realizing that Colonel Bealke couldn’t get to me in time, I ordered a withdrawal. I ordered those men not seriously wounded to assist the seriously wounded in getting back to the infantry line. In my opinion, every man who could walk and see left the field. I also requested that an aid man and three litter teams be sent to me as soon as possible. An infantryman who had been shot in both legs, my gunner, who was horribly burned, and I remained in a small field adjacent to my tanks.

I can’t imagine why those SS paratroopers didn’t jump over the hedgerow and kill the three of us. The only plausible explanation in my opinion is that they thought we were already dead or would die very soon.

Several hours later, a German aid man did come over and look at us. He did nothing for the infantryman. He bandaged Corporal Rothschadl’s hands. He looked at my right leg and checked the belt I was using as a tourniquet, then he bandaged my hands. That was all. I asked him to give us water, but he refused.

The next day, 11 July, very early in the morning I heard men walking along the other side of the hedgerow. I thought it must be the aid man and the litter teams. I called out to them but received no reply. Sensing that it was an enemy patrol, I secured a tommy gun and two magazines which were nearby. I rolled over to the hedgerow and crawled on top of it. I saw several German soldiers walking away from me toward the American line. Becoming enraged, I emptied both magazines in their direction. I don’t know whether I killed any of them. They disappeared at once, probably thinking it was an American patrol firing at them. I didn’t see them again.

Later in the morning, a German force of about one platoon came into my field and dug in. They didn’t bother the three of us who lay there wounded.

They had already finished digging in when our own artillery opened fire on this field. The German artillery is good, but ours is much better. Countless numbers of shells fell in that area. At times I was deafened by the explosions and covered with dirt.

The Germans were terrified in their holes, as were we three Americans on top of the ground. We were almost paralyzed with fear.

Several Germans were killed and wounded in the barrage, which lasted for what seemed hours. My gunner didn’t get hit. A shell landed between the infantryman and me, which hit both of us. One shell fragment hit my left leg, knocking it off about seven inches below the knee. Other pieces of fragment hit me in both legs above the knees and in the back.

“My platoon was composed of the most courageous men on earth.”

I immediately tied my belt around my left leg as a tourniquet. The infantryman called to me that he had been hit. I crawled to him and saw blood spurting out of his right leg. Taking his belt, I used it as a tourniquet. Because of my burned hands and German bandages, I was unable to twist it tight enough. With his helping me turn the stick, I was able to stop the bleeding. I tore his clothes off as best I could to look for further wounds. He had been hit in several places on the right side. I had no first aid kit, therefore I was unable to do more for him except to bandage him with strips torn from his shirt and pants leg. When I had finished with him, he was apparently resting as well as could be expected. There was no excessive amount of blood lost.

During the rest of that day, I maintained close watch on both our tourniquets. The artillery fired a few volleys every hour for the rest of the day. It was HELL!

Sometime after noon of the next day, 12 July, the infantryman told me he was getting to die. He said that our infantry would never attack through our field and find us. I knew that if he continued to feel that way he would surely die. I assured him that our men would find us, and soon. I used every argument I could think of to persuade him to want to live. For a while I was successful. Later he said that he was dying. I tried everything again. I begged him. I bullied him. I pleaded with him. But I failed. I was holding him in my arms, praying to God to not let him die, when he took his last breath. I was heartbroken to lose him and I, too, wondered if our men would ever find us. Again I asked Him our creator to send aid. No man can know the HELL of losing both feet and wondering if his men will find him in time to save his life until he experiences the things I did in that field.

About an hour after the infantryman had died, I heard small arms fire near my position. I knew that it was our men making an attack. In a few minutes, our infantry came over the hedgerow chasing the German paratroopers. The first man I saw was Lieutenant Claude H. Lovett of the 357th Infantry. I called to him, and he came to me. He gave me a canteen of water and left one man with me until a litter team came to evacuate Corporal Rothschadl and me. I knew then that we were safe again.

In closing, I want to emphasize that my platoon was composed of the most courageous men on earth. They fought and died valiantly. I admired and respected each of them. Without their aid and willingness to follow me anywhere at any time, I could not have accomplished the missions which I understood. To the enlisted men of my platoon goes all the credit for my success as a soldier.

Respectfully yours, James F. Flowers

*The 5th Fallschirmjager [paratroop] Division was not an SS division but rather was part of the Wehrmacht.

**Lieutenant Harlo J. “Jack” Sheppard was actually the company commander, having taken over the position when Captain Jim Cary was injured by a booby trap on the battalion’s first day of combat.

“Did he tell you about the turning plow?”

I forget who asked me that, but he surely did. Flowers was from Richardson, Texas, and rarely missed rarely missed an opportunity to relate the story of Hill 122. And he usually included the turning plow.

I was a country kid. I’ll tell you a story, it’s not the whole cloth, but it makes it interesting. Up in the spring of the year, the weather started getting hot. I was out in the field plowing, behind a turning plow. We were not wealthy enough to have a plow that had two wheels and a seat on which I could ride. I had to walk behind a team of mules and hold the damn plow up, walk behind them to plow. That’s a dirty damn job. That’s just one of the things that I didn’t like about the farm. I never did find a hoe handle that would fit my hands. Chopping cotton. You’ve heard the expression chopping cotton? They plant cotton, they plant too much, and then after the cotton gets up so high, you go and you chop out the weeds that’s growing around the cotton, you chop out the unwanted and unneeded little cotton plants, to give the ones that you save a fighting chance to grow up to be nice, healthy plants that produce a lot of lint for the cotton. You with me? A lot of other things I didn’t like about the farm, but I guess those were a few of the things that I didn’t like most of all.

Now, back to the interesting, not whole cloth story. I was plowing and I was hot, I was tired and I’m dirty, and the damn mules were contrary. I just plowed over to the next fence. Barbed wire fence. I plowed over to the next fence, and leaned the plow up against the fence post, unhitched the team, and headed them toward the barn and threw some clods at them to get ’em moving that way. Once you get the mules headed toward the barn, why, they’ll go, as a matter of fact you may have a real problem stopping them. And I jumped over the fence and walked out a little better than a mile to the highway, and thumbed a ride into the city, and never went back to the farm. Makes a pretty good story.

I was an old man. I was 17 years old. It was 1931.

I wound up, you know what a chain tong is? I bucked a chain tong and worked around the oil patch, and I came to the attention of a man named McLoughlin, who was the vice president of production for Magnolia Petroleum Company. That kind gentleman saw that I was fairly intelligent and not lazy by any means, and I would work, I knew how to work, so with his taking an interest in me, why, somewhere along the line I became employed by the Magnolia Petroleum Company and got a little education along with it.

I guess had it not been for the outbreak of the war in Europe, why, I might have been Mister Flowers with Mobil Oil before I retired. I like to think that I would. That’s the way it goes.

1st Lieutenant Claude Lovett describes finding the badly injured Flowers, while the 90th Division band performs in the background at the 90th Division reunion. Then Lovett is joined by Jeanette Flowers, Jim’s wife, and then Jim. (There is no transcription). Caution: contains graphic descriptions.

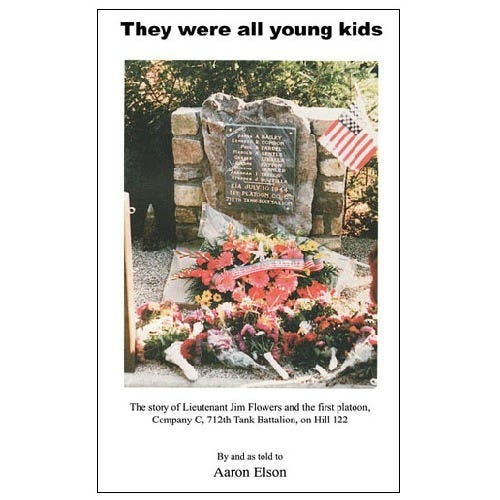

For more on Jim Flowers and the battle of Hill 122, read “They Were All Young Kids,” available at Amazon and for Kindle.