This is a War Story? Where's the War? Part 2. Why, here it is

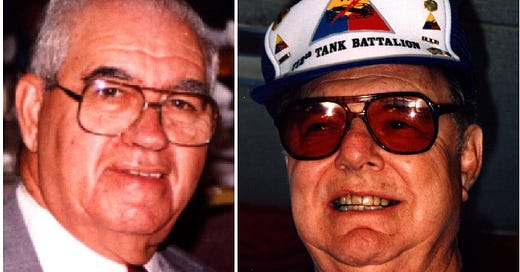

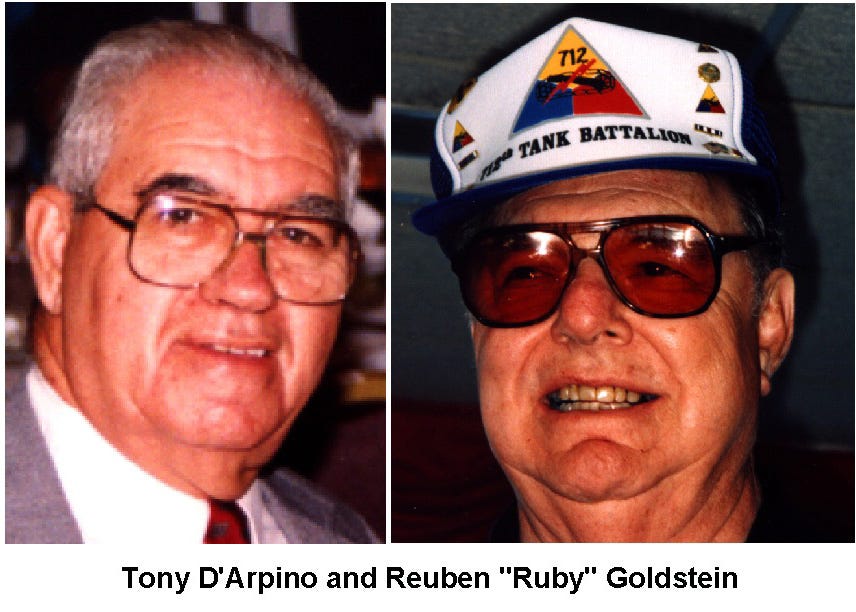

More from my interview with Tony D'Arpino and Reuben Goldstein

A few Substacks ago, 712th Tank Battalion veteran Reuben “Ruby” Goldstein told a story about the best tasting water he ever had while taking part in the Tennessee maneuvers. Ruby was a tank commander in A Company and Tony D’Arpino was a tank driver in C Company, and I interviewed them together in 1992 at Tony’s home in Milton, Massachusetts. Lest you think, though, that all they talked about was food, well, they did talk quite a bit about food, which is partly my fault because I asked a lot of questions on the subject, but they also talked about combat. So here is some more of that interview. First, though, a bit more about food. But also, the subject of cowardice comes up later in the interview. Lieutenant Jim Flowers, who lost four tanks with nine of 20 crew members killed in the battle for Hill 122, believed that the tank commander of the fifth tank chickened out of the assignment. After I learned of this during my interview with Ruby and Tony, I interviewed both Don Knapp, the gunner in the fifth tank, who explained that the tank would not go into reverse and thus was unable to join the other tanks on the mission; and Jake Driskill, the maintenance sergeant who confirmed that there was a problem with the transmission and was able to repair, it, but after the other tanks had left.

Aaron Elson: What were the rations like?

Tony D’Arpino: I remember when we first went over there we had the cans, right? There were three different kinds. There was meat and vegetable stew, meat and beans, and hash. Now you had to have one of them for breakfast.

Ruby Goldstein: Yeah, but then we had another can, with the crackers.

Tony D’Arpino: That was the box.

Ruby Goldstein: Not the C rations.

Tony D’Arpino: Yeah, the small cans of crackers, the round crackers. There were ten crackers in them. I remember that now.

Ruby Goldstein: You have peanut butter.

Tony D’Arpino: Peanut butter.

Ruby Goldstein: Peanut butter. Because that’s what I ate when I got hurt one time.

Tony D’Arpino: And there was butter, little containers of butter. You couldn’t even melt it. You put it in a frying pan...

Ruby Goldstein: We used to bitch a lot, and why? Because those in the back, like maintenance, service, headquarters company, they couldn’t keep up with us, there’s no way, because they’re not protected like we were with our armor. So they had rations; their rations were good. We had to scrounge. Whatever you had with you, that was it. You couldn’t say, “Well, let’s send somebody back and get some stuff to eat.” Uh-uh. You couldn’t. We were way ahead. We didn’t know where they were. They didn’t know where we were. But we survived.

Tony D’Arpino: I remember once it was wintertime, and we took this small town, there was a farm, and they must have just killed a cow, because they had like a hind quarter hanging up. Some stupid guy name of Klapkowski [Stanley Klapkowski, the gunner in Tony’s tank], he took it and put in the back outside of the tank. The goddamn thing froze solid. I says to him, “What good is that?” He says, “Whyyy, we’ve got an axe on here, we just chop off a piece.” It was just as hard as this table.

But the Germans, once we got into Germany, they used to can everything. I don’t know if you ever came across it, but the sausages, they put them in jars. And they were all cooked. And they put the white lard, pure lard, white as snow, there’d probably be a dozen sausages in there. And pork chops. All cooked. We used to love to find them. You know, just find a skillet someplace, start a fire, and just heat ’em up.

And cherries. Jars of cherries. They could have poisoned them; we’d eat more of their food when we went in these small towns than we did our own, because we never got any.

But then toward the end we got pretty good rations, 10-in-1 rations, they weren't bad.

Ruby Goldstein: That was fine. It was better than what we had before.

Tony D’Arpino: They had cans of bacon, sausage meat, and even a fruit cocktail.

Ruby Goldstein: Spam. How can you forget Spam?

Tony D’Arpino: And crackers, and little bars of chocolate.

Aaron Elson: How did you make coffee?

Ruby Goldstein: We had a little bunsen burner. You opened it up, put gasoline in it, and started a fire. And a wick. And you’d put a can on it, or your canteen cup, you’d heat it up. It was instant. You couldn't get any real coffee. Where could you steal that?

Tony D’Arpino: And if you ever did find it, we did come across some coffee grounds, I don’t know, from a house or what, they put it in this can I had, right, start a fire, boil water, put the grounds right in it. And then you get some cold water and put it on top, and all the grounds would go down to the bottom.

Ruby Goldstein: That was living it up.

Aaron Elson: You said that one time when you were hurt, you ate, what was it, peanut butter?

Ruby Goldstein: Oh, well, that's when I had, it wasn't Watson, in fact they had to get rid of No. 4 tank, I was No. 5, I forgot his name right offhand. [The tank commander he’s referring to was Sergeant Charles Fowler.] But anyway, when we got called on for the airborne troops — we were attached to the 82nd if you recall in the beginning — and they called up some tanks to help them. And when you're going somewhere, you’re going blind. They tell you, “Go down to the road,” and that’s it. But you’re wary, you don’t know where you’re going, you don't know what you’re gonna meet. You're going blind.

I come down a country road, and there’s hedgerows here, there’s a field over there. And I come across and that’s a dead end; I’ve got to take a right. As soon as I take a right, Baanng! We get it. What is it? An anti-tank gun. Breaks my track. And when you break your track, you’re stuck. You can't move.

Tony D’Arpino: You can just take the broken track and you put it on the big front sprocket, and by pushing the magnetos together, it kind of brings the track into place.

Ruby Goldstein: We carried extra blocks with us. That’s if you were fortunate enough, you didn't get them shot.

Tony D’Arpino: But in real combat, we used to destroy the goddamn tank before you try doing something like that. If you had to ditch a tank, you didn’t want to take a chance of the Germans taking the tank over, so you’d destroy it.

Ruby Goldstein: So when they broke my track, I had Charlie Bahrke, he was my gunner, and the 75 was loaded; I just hit him right in the back, and when I hit him in the back, he knew, Bingo, let it go. And that 75, just like in a bowling alley, with pins, it went right down where the anti-tank gun was. A little Pfft. Machine gun nest, anti-tank gun, everything flew.

All of a sudden I hear firing. We’re on the road here, and there’s bushes here, and they’re firing in the field. But there’s an opening over here, and there was an opening further back.

So I was 5, not 5, Charlie [note that on the first reference he said he didn’t remember Sergeant Fowler’s name] was in No. 4 tank; it was way back there, before the other opening. When I started to hear the machine gun fire, do you remember, we had flare guns? A regular flare gun.

Tony D’Arpino: They were used for smoke, too.

Ruby Goldstein: It was wired to the inside of my basket in the turret. So I undid the wire, took the flare gun, loaded it up, and from my turret, it lobbed it right over the hedgerows, must have scared the heck out of them. Where the heck it was coming from, you know. But anyway, I jumped out and I says to the fellows, “I’ll be right back.”

I go around, from where the tank was here, I come around here and go over here, now there’s an opening here. A paratrooper’s there. I said “Stay where you are, because there’s a machine gun nest in there.” It wasn’t going, but I knew there was one there because I heard them firing before, and he's probably covering that opening.

So I said, “If you’re gonna come over, make like a snake.” He wasn’t. He was crawling. You don’t crawl. We were taught not to crawl. If you remember, you went through basic training, through barbed wire, and they had mines set up, you know, not to hurt anyone. They told you dig, anything, you could crawl but flat.

He got up and all of a sudden, zzzzooop. Then he dropped. I reached over, I laid on my stomach, and I grabbed ahold of his jacket, and I pulled him over to this side. He was dead. But nobody else came over.

Then I went back to the tank and threw some more shots from the flare gun over. Either it scared the hell out of them, but they beat it.

Now, all of a sudden, I hear a shot, a big gun going off.

I run over; Charlie had gone into that other opening, Charlie Fowler. And I’m trying to tell him I saw where the shots up on the hillside were coming from. That’s not a machine gun firing up there. It’s shells.

So he’s buttoned up. I take out my .45, and I'm banging on the tank, and I’m screaming, hollering, “Open up! I want to tell you where to” fire his gun. I couldn’t where I was. I wasn’t moving. But he had a perfect place for it.

He was No. 4 tank. I was 5. I went in first, and he stayed back. He’s supposed to go first, he’s supposed to be in front of me, but he didn’t [Fowler, as the platoon sergeant, was supposed to ride in the fourth tank]. But I think they got rid of him because he did something bad afterwards.

And he wouldn’t unbutton. And don’t tell me you can’t hear the butt of a .45 hitting the turret of your tank, and I was banging on that. But then again, you can’t blame him. They could do this if you unbutton: Pfft, throw in a hand grenade. Kills everybody in there. That's all they have to do. Or if your gun barrel is not elevated too high and your block is open without a round in it, that's what they do. Throw a grenade right down into your barrel, kill the crew.

Anyway, he wouldn’t unbutton. But they saw him, because they fired. And when they fired, here’s the hedgerow, and me right here in this opening, and I'm banging on this tank here and hollering, but no response.

They hit on this side of the hedgerow and I’m on this side. And the force was so great of this shell landing here, they didn’t hit him, they hit on his left side as he was facing toward them. Picked me up off the ground. Bodily. Picked me up and I fell down.

I get up, and I started to bang again, and I'm screaming.

Now, another one hit, on this side of the hedgerow, which it was fortunate for me. On the opposite side here, and I'm on this side of the hedgerow. When it did it picked me up this time, only this time I don’t get up. This time, my head is a balloon, and it’s growing bigger, bigger, I’m gonna burst, that’s how it felt. And I says I bought it. And I stayed there for maybe a minute. I crawled on my hands and knees across the road. I got up on the other side of the hedgerow, and I lay in the bushes for two hours. And I felt like that was it, I’d had it. But everything subsided. I was okay. I had a can. I opened the can, had some crackers and peanut butter and a drink of water. And everything was fine. I got back to my tank, and they were good. They didn't come out. They stayed in the tank and they kept their eyes open for anything that was coming.

And I got back to them. Then we got word, and they came up and they fixed my track. But before they came back, two men come down the road, everything is quiet now, and I don’t know who they are; I mean they’re Americans. They come down the road, and I see they’re officers. One is an aide and one is a general, but a one-star. Dirty. They have to be dirty, because that’s the first thing the enemy will go for, if they see any identification of any kind that there’s an officer, this is the one that’s gonna get it first, because he's in command of some group.

So I told him what happened. He asked my name, rank, serial number. And he says, “Have you got anything to drink?” But I had dumped my canteen of water out, and there was a hut in the back there, and they had big cider barrels. We dumped our water out of our five-gallon can, and we filled it up with cider. It was apple cider. It wasn't to get drunk on, but it was better to drink than just plain warm water. The water was warm. You remember drinking that good water? That nice, clean well water.

Then, I says yes, so I take out my canteen, and my cup, and I give it; he says, “What is it?" It didn’t look like water. I says it was apple cider. And you know, you have to use your head, but you don’t think. When I first went to get the apple cider at the time, they could have had that bugged. But I guess they didn't expect it; it couldn’t have been bugged because they were still there. They didn’t bug it and then leave. So when I went there, we all of us filled up our canteens, and I gave him a drink. He says, “It’s not bad.” And he gave his aide some. Then he had my name, rank and serial number. I never saw him again. He disappeared. Wherever he went, inspecting his troops and so forth. [This action took place on July 5, 1944, only the battalion’s third day in combat. Ruby and his gunner, Charles Bahrke, were both awarded the Silver Star, the first two of more than 50 eventually awarded to members of the 712th.]

But they got through, on account of that blocking the road. But they had everything. But you see, they, you know that, they didn't play nice. If they captured somebody, where are they gonna take him back, to their quarters? They kill him. Our soldiers. So what do we do? We retaliate. You do that, if you capture a prisoner, what are you gonna do with him? You're supposed to go with the rest of your men somewhere, you had some destination, what are you gonna do, are you gonna drag him with you?

So they caught some. And I says to one of the paratroopers, “Well, we have to turn them in.” You have to turn them in, they're gonna interrogate ’em, get whatever information they can out of them, and that was it.

Tony D’Arpino: We captured a couple of Germans. Klapkowski...

Ruby Goldstein: They didn’t do that. They disappeared, and I’m hanging around my tank waiting for them to come up to fix my track. Brrrrrrrrp. That’s it. But the word came down, no more. Keep the prisoners alive. They couldn’t get any information. Why? They were knocking ’em off. But they were knocking ours off, too. If they caught us, they’d frisk you; they’d take whatever they wanted away from you. They weren’t gonna leave you, say “G’bye now.” Uh-uh. Bingo. You're gone.

This was in Normandy. Hedgerow country.

One time, we were in this farmhouse, and I asked if they had anything to drink, with whatever little French I knew. And he understood what I wanted. So he told me to wait outside. And I watched through the window. He took open a drawer, built into the wall, opened the drawer, took the drawer out, and inside he had bottles. He took out a couple of bottles, put the drawer back in, he came out. And I gave him a pair of shoes. But you know why I gave him the pair of shoes? It was an extra pair of shoes I had. There were two left shoes. Somebody switched by mistake, and took one of my shoes, whoever it was had two right shoes. So I gave him the shoes.

But that stuff was dynamite. Calvados. Powerful stuff.

Ed Forrest was my platoon leader in Normandy. When I was with him, he was No. 4 tank, I was No. 5. We got up near some apple orchards, and we got a barrage. I was outside the tank, and so was he. So the first thing you do is take cover, and where are you going to take cover? The safest place is under the tank. But Ed couldn't get back fast enough to his tank, so we went in the bushes, in the hedgerow. So I jumped in; I went right with him, I've got my arm around him, and they were still shelling. The guys in the tank, they buttoned up. Charlie [Bahrke, the gunner] buttoned up the turret opening. And George Bussell, he could barely get into the tank, he was the driver. Eugene Goad was my assistant.

Anyway, we’re gettin’ it, and you’re praying that nothing hits you. But he got hit. And I didn't know it. I had my arm around him. It’s fate. That’s all I can say it is, it’s fate. Because when I said “Okay, Ed, everything’s okay, let’s get going,” uh-uh, he was hurt. So I don't know who the heck came up with a stretcher, we put him on the stretcher, and we got him on the road near a first aid station, and they took him away.

He was from Massachusetts. Because they tried to contact his family, and I don't think they were too happy about talking to anybody, his family, at the time. I tried to contact them.

Now, when we were at the mines, remember the Merkers salt mines? And we surrounded, all the tanks were around, there was an open field in the back, and McCarthy, from Connecticut, he worked in the kitchen crew, and he was put on guard duty. Now Alfonse Switer, he was the company cook, and he had to go to the bathroom. So he went. McCarthy thought the Germans were coming across the field. It's dark. I was upstairs in the mine building, on the third floor, I had my shoes off, I had my clothes on, I had my .45 and my submachine gun with me. And I hear shots. I come running, everybody, running like crazy, you know, you think something's happening. I come running down, and Al is hollering “Goldie, Goldie, help me, help me.” And everything else is quiet. There’s no more shots.

McCarthy thought it was the Germans coming and he shot his carbine. In the leg. But he did not know that it was one of our own men. It was what you call friendly fire. Accidental. So they took Al away, and nobody ever saw him again. And the reason they never saw him, because nobody knows what ever happened to him after that. Till the beginning of January of 1946. My brother and I, we bought a second-hand car, and my mother and I, and my brother Mel, he got out of the service after I did. My other brother came out after that. We picked up my aunt in New York and went to Florida.

On the way back from Florida we stopped in Pennsylvania. We stopped at a gas station to gas up, and I said, “Why don't I call Al’s house?” He lived in Manayunk. I get in the phone booth, and my mother and my aunt and my brother are sitting in the car. And I call up information, I get the number, and I don't know how to ask for him. I don't know if he's dead or alive. So I got the number, and I asked if this is the Switer residence, and this girl answered, and it was his sister. “Oh, my god,” she says, “how nice to hear from you. Would you like to talk to Al?” Well, I nearly flipped. I got on the phone; “You S.B.,” he says, “I thought you were dead.” I says “I got news for you, I thought you were dead.”

I says “Nobody’s ever heard from you.” He was in so many hospitals; he had 26 operations, and his leg was gone all the way. Gangrene had set in. They made him artificial legs, and at first he was walking with the artificial legs with crutches, and then with a cane, and then he could walk on his own. I found that out. We went to a Polish dance one night, and he was dancing with an artificial leg as good as anybody.

Tony D’Arpino: We caught a couple of prisoners. Klapkowski captured a couple of prisoners. He took one of the German’s wallet, and he's looking for pictures or something, right, and there was a picture in there of a German soldier, and they had this girl on the table. There were two soldiers, one holding each leg apart, and this, the one that he captured, was there, ready to...you know...Klapkowski turned around and Wham! He hit him. Now they radioed ahead and told them we had two prisoners that we wanted picked up. So we’re waiting for them. Now this guy, he’s got to go to the bathroom bad. And Klapkowski says to me, “That sonofabitch is gonna shit his pants; I ain’t gonna let him pull his pants down.” I can see this stupid bastard, we’re gonna stand here and smell it. He did, he made that guy mess his pants. Then they finally came and took the prisoners. Those were the only two closeup prisoners I ever got.

[Here there was a break in the tape — them old analog cassettes had to be flipped over, and the discussion shifts to training, but not for long…]

Ruby Goldstein: You had to line up and get your clothes issued, you remember? We went out on a platform, this is in January. It’s cooold out there.

Now civilian clothes, you’re not supposed to bring anything, only what you’re wearing, a little bag with some little stuff, that’s it. Nothing else. And we had to disrobe right on the platform. Put on long johns, and put on your uniform. They’d just look at you and this is the size, whatever they gave you, that was it. Too big, too small, you got it. We dressed fast, because it was too cold out there. Then when we got back inside the building, it was like a huge hangar in there, and then from there, they put us on the train, and we wound up, just like you wound up going to Benning, we wound up going to Fort Riley, Kansas. But we didn’t know where we were going.

They’d ask you, “What do you want, mechanized or horse cavalry?” I liked horses, so I picked horses. And when we got to Fort Riley, next thing you know, wherever you were told to go, that's where you went, I wound up in a barracks on the side of the field where the horse cavalry is, and way the heck on the other side was mechanized cavalry, and you went through your basic training.

They (D’arpino) had their basic training down in Fort Benning, but while they had their basic training, we as cadre were getting basic training, we were never in tanks. All we knew was horses. When we went in, we had O-3 rifles. They had .45s. The old Thompson submachine gun, that’s what we had. It didn’t come later on till we got the Buck Rodgers machine gun, remember the Buck Rodgers machine gun?

Tony D’Arpino: They were made out of tin cans.

Ruby Goldstein: The tube was like a pipe, and the handle could slide in and out.

Tony D’Arpino: A very cheap gun.

Ruby Goldstein: But the Thompson submachine gun, the stock had wood in it. That was the old Thompson submachine gun. And we had an Enfield rifle, and an O-3 rifle from World War I. And this is what we took our training on. At the firing range, and on horseback, you had to fire, as you're going at a gallop, they had silhouettes all lined up, and you had to get on a gallop, and put your head forward and shoot at the targets. One fellow forgot to release his safety on his .45, he got scared, pulled the trigger, it didn’t go off. He threw it away. When he threw it away it hit a rock or something, and it went off. You know what you saw? All the horses, in all directions. Someone could get killed. He didn’t last long, that kid. But it was dangerous, you don’t do that. But those O-3 rifles, they had a kick. If you didn't hold them right on the firing range as you were lying down shooting at a silhouette, at a target, if you didn't hold it right, when you got through that day, either your jaw was going to take months to heal, because it had a kick.

But then they came out with a Garand rifle. Those are lightweight, very easy to handle.

Tony D’Arpino: They worked it a little bit different with us. We went into a big hangar like, too, and they had a clothes and supply room. And they took your civilian clothes from you, and they had boxes for you to put them in, they sent them home. And then you go up to a guy, and he put his hand around your neck. “Sixteen and a half. Give him three.” Put one on you, two in the duffel bag. You come through there, you’re looking like Sad Sack. The shoes are so goddamn big you could turn around inside of them. They don’t even give you a chance to lace or nothing. All the tags on the pants, the pants are about six inches too long, the overcoat. That's how you got your clothes.

Ruby Goldstein: Take a look (displaying a photo). Remember I told you about the guy that got shot with the machine gun. There he is with me, I’m holding my canteen cup, and there he is beside me. That’s Duane Minor. That's the kid that got shot, the machine gun was so hot from firing it just kept firing because he didn’t pull the bolt back. That’s me with the cigar in my mouth. I always had a cigar. And there's Steve Krysko and myself sitting down. Charlie Fowler in the back.

Aaron Elson: You said that Charlie Fowler did something bad.

Ruby Goldstein: Not with me. On his own vehicle. Some of the fellows know the whole story, but from what I gather, he put a piece of a branch or wood in the turret ring, and if you put it in the turret ring, you can't traverse. So what does that mean? You can’t use your 75. Right? Somebody found it, and they claimed he did it. I don't know if he's dead or alive, or what.

Aaron Elson: Why would he do something like that?

Ruby Goldstein: It wasn't talked about.

Tony D’Arpino: There's a lot of little things eating at, in individual tanks, you hear about, but you don't always know the whole story. Like myself, I know that Lieutenant Flowers’ platoon, he had the first platoon, and he lost a lot of men on that Hill 122. Now one of the drivers in that platoon was a guy named Paul Farrell. He came from Haverhill, Mass. A handsome guy, he had red hair, he was married. We were very friendly because we came from the Boston area, when we were at Fort Benning, we used to go to the bars together. And there was another kid named Savio, he was from Boston, he was in our group.

He was in the first platoon, and I was in the third platoon, so we didn't get to see each other that often.

We came together one day, and I asked for Paul Farrell, and one of the guys says to me, he says, he was the driver, "He's sitting in the tank. He won't get out." So I go over, I drop myself down into the assistant driver's seat, and he says "Hi." I said, "What's the matter?" He says, “We ain't gonna get out of this alive.” I said, “You really believe that?” He said “Yeah.” I said “If I thought that,” I says, “I'd get up, take off. Go back. Over the hill.” I said, “You're gonna get out of it alive; don't worry about it." “Nooo,” he says. “Never.”

He got knocked out.

Last time I ever seen him. And that guy there, even in the States, we used to have like, when you had company guard, and you go to guard mount, they always used to give a 24-hour pass to the best-dressed. The best informed. Best-dressed, he got it every time. He was just made for the uniform, he had a build, the shirt fit just perfectly, like a model. And he always got the best-dressed. [Paul Farrell was one of nine members of C Company’s first platoon killed on July 10, 1944, in the battle for Hill 122 in Normandy.]

I can remember, we had a young kid — young kid, we were all young kids — but the loader on our tank was Luigi Grameri. He came from Utica, New York, and he was probably a year and a half younger than I was. And we had the honor to go back up the Hill 122 after Flowers got knocked out. We were gonna go up there and take it. And Lieutenant Lombardi, we were in Lieutenant Lombardi’s tank, and Grameri threw a tirade, “You stupid sonofabitch,” he's saying, now this is Grameri, he weighed about 110 pounds, he says, “You're gonna go up, all the goddamn first platoon just got killed and you're gonna go up there?” I grabbed him. I said, “Get in the tank, will you, and be quiet.” And one thing led to another, and we finally made out all right, but he was going, because he'd heard about all these guys that, you know, and now we're going to go the same thing, how crazy can you be? He was telling Lombardi, but Lombardi was taking his orders from the infantry.

So anyway, it was getting dark, and he thought we were going to go right then and there, but we waited until the next morning. By the next morning everything turned out pretty good, we made out all right.

Aaron Elson: Ed Spahr told me that once you were driving through a woods, and there was somebody in the tank who said “We're not gonna make it out of the woods.”

Tony D’Arpino: That was Klapkowski. Klapkowski, the same guy, to Grameri. He’s the one who got Grameri in this condition. I finally told Klapkowski off. He’d say, you know, Klapkowski was the gunner, Grameri was the loader. And Lombardi was the tank commander, in the turret. And Klapkowski would say to Grameri, “We ain’t gonna make it. You know what's gonna happen?" he says, “some day,” he says, “the tank’s gonna get hit,” and he says, “Lombardi's gonna go to get out, he’s the first one to get up, he's in the turret there, he’s gonna get shot and he’s gonna come down inside on top of me, on top of you, and you ain’t gonna make it, and the tank’s gonna be on fire,” and I, I just blew up, I just told him, “Stop talking that way.” Because he’s making me scared. He liked to talk, Klapkowski. I used to tell him, “Make sure when the tank gets knocked out that that gun is in the middle. And if it ain’t,” I says, “so help me god, I'll haunt you, I'll pull the sheets right off the bed.”

Ruby Goldstein: If you have that gun over the cover for the driver or the assistant driver to get out, how's he going to open it? So he's got to go through the escape hatch underneath. And the only way out up in the turret is up through the hatch, or there was an opening in the basket, remember, an opening in the basket, you can go into the driver or the assistant driver’s seat, if it was turned the right way, the turret. But if it was turned this way, you can’t make it, too small.

Tony D’Arpino: He had Grameri so scared, here’s how bad it got, and I ain’t kidding, I shouldn’t even say this because you’ve got a tape on. Here’s how bad it got. If we were in combat and we were getting fired at, right, and he had to go to the bathroom, Grameri, we used to keep the empty boxes from the .30-caliber machine guns, he’d piss in it. And then he’d reach down where that opening you were talking about, and he'd hand it to me, the driver, to throw out the hatch.

I finally said, “Hey, Grameri,” I said, “when I have to go, I go outside. You do the same thing," because I was trying to get him so he wouldn’t be so scared.

Klapkowski was one of the best gunners that the company, the battalion had. But he was also ... because I know, after you hear this, you can either leave it out or do what you want ... They had five syringes of morphine, one for each man in the tank. Now, in our platoon, third platoon, Lombardi, the platoon leader, wouldn’t let each guy keep his own. Wouldn’t, no. He was afraid they’d lose them. He figured one man should have them all. So he gave them to the gunner, and they scotch-taped them inside the helmet lining of the gunner. That's the last we ever saw of the morphine unless we needed it.

So this tank that [Lieutenant Jim] Gifford had, Klapkowski's gone back to the States now on a 30-day furlough because he’s got the silver star and all this other bullshit, he and Lombardi both had gone back to the States on a 30-day furlough. Gifford takes over that tank. When we had it knocked out, we had to destroy the radio. When I destroyed the radio, I found the five empty syringes. This is what Klap was taking. He had a very nervous habit; he kept taking his handkerchief and wiping his face, a thousand times a day. Everybody else was going around getting souvenirs — guns, daggers, whatever, medals. Klapkowski: perfume, nylons, anything for the ladies, and he made out like a bandit.

I told you the story about the paratroopers in Fort Benning. I used to go to Mass with Klapkowski every Sunday morning. I never went in town with him, because I knew he was crazy. I hung around with the guys from Massachusetts, and that was it. But anyway, one Sunday morning, I wake up Klap, we used to call him Klap, and the blanket’s over his head. I’m shaking him, and he ain’t waking up. So I pull the covers down, I didn’t recognize him. His eyes were closed. His face was twice as big as it usually was. It scared me. So I went and got the motor sergeant, he used to have his room right in the barracks, in the front of the barracks he had a separate room for himself, I went and got him, and we took Klapkowski to the medics. He had gone in town the night before, and he saw this paratrooper who reminded him of something, and he picked a fight with him. He said there were three or four of them who jumped him. But anyway, he was in the hospital for a week.

Ruby Goldstein: I had a similar incident. My driver, George Bussell, he was a stocky, he was so stocky that when we went through basic training, they had like a ditch, in order to help somebody who got hurt, you had to carry them. How are you gonna carry? So you’d have to get on your back, and you’d have to crawl with him. I’m a hundred and fifty pounds or so, this guy’s two-fifty. It’s like putting an automobile on you; how are you gonna carry him? But I carried him. That's how heavy he was.

We go into town; we go to Phenix City, right over the little bridge from Columbus into Phenix City...

Tony D’Arpino: That was off limits, yeah.

Ruby Goldstein: And they’ve got a barroom here, a barroom here, no matter which one you go, there’s girls with the dice to sucker in the soldiers. So we went in here, we went across the street, and we stand at the bar, George and I, we have a drink. And we hear this music, and there’s another room over here. We walk out, we go into the room, there’s a couple of civilians sitting there, a couple of girls. I went to the bar, finished my drink, and George leaves. Next thing I know I hear a commotion. George goes in and he asks the girl to dance. She accepted. He’s on the dance floor with her, then all of a sudden I hear something, I don't know what the hell it was, I hear a lot of noise.

So I run in there. George is on the floor, the girl is on the side, and this guy’s got a chair and he's whacking at him. He objected, you know the Southerners objected to him dancing with one of their girls. He’s gonna lift the chair up to hit him with it. I grabbed him, and I suckered him one. A guy got up from the table, grabbed me and suckered me one. Now we’re all on the floor.

I got up; I went crazy. And he got, he was banged up real bad. Now I’ve got to get him out of there, because I know the two of us are not gonna last too long.

I got ahold of him; we got him out, and I know damn well the MPs, if they grabbed us, we’re locked up, forget it. Anyway, I got him out of there, I got him back to camp, and his face was so beat up, just like what you were talking about. And why? He had a few drinks, he had no business asking the girl to dance. And this is what happened.

Now this same George Bussell is alive. He’s never corresponded with anybody. He’s never attended a reunion. And he lives in Indianapolis, Indiana. He’s in the book. And they tried to contact him. He won’t have anything to do with anything.

Tony D’Arpino: What I was saying about being sensitive about things, I never knew this, but Flowers at Hill 122, so we were at one of the reunions, I forget which one it was now, and Jim Flowers was talking to me. He likes me; he always says “Always glad to see you.” He knew me a long time, because he came from B Company to C Company; he was very nice.

I said, “You know, I remember you, and this lieutenant we used to have named O’Grady, and he finally stayed with the 10th Armored Division, O’Grady went back to the 10th Armored Division. And I says, “That Duval was a no good bastard,” he was in the second platoon. He (Flowers) says, “Yeah, I knew him." He said even the officers didn't like him.

Then I said I remember the sergeants we had, the first sergeants; we were one of the first recruits down in Fort Benning, and I remember like Sergeant Ellis. I says, Sergeant Montoya. And he says “Don't ever mention that goddamn name.” Now, I never knew nothing between those two guys. “Don't you ever mention that sonofabitchin' yellow bastard’s name in front of me again.” He was jumping all over him. I didn't say anything more. So, you know Byrl Rudd, Sergeant Rudd, he hasn't come to the last few reunions because he was in a fire or something, so I grabbed him, because he's very friendly with Flowers. I says “Jesus Christ,” I says, “I'm shocked. I just mentioned Montoya's name to Lieutenant Flowers.” Oh, Jesus Christ, and he told me the whole story. I never knew about it. I used to be in a different platoon. I never knew this thing happened. He evidently got yellow when Flowers needed him and left him in a bind. [As I mentioned earlier, both Don Knapp, the gunner in Montoya’s tank, and Jake Driskill, the maintenance sergeant, confirmed that the fifth tank in Lieutenant Flowers’ platoon had a problem with its transmission. Montoya performed well until he was wounded later in the war.]

This is one thing about the tanks, you're dependent on one another. I mean, when you have five guys in a tank, and they put you on guard duty at night in enemy territory, they've got to depend on you being awake and not asleep because they might wake up dead. So you had to depend on one another.

I always said, the Air Force had it rough, but when they got through with their mission they went back to a nice barracks, hot meals, showers and everything else. The Navy, the same way. They're on the ship. They have their battles and then you've got a bunk to sleep in, they got cooks cookin’ for em.

Us guys, no heat in the tanks in the goddamn winter. I remember digging out snow, putting branches down on a blanket, and a blanket on me; when I woke up in the morning I had about twelve inches of snow on me because the wind was blowing. We had a rotation plan in our tank. The engine compartment, that stayed hot almost all night. We used to take turns, one night apiece, sleeping on the engine compartment. You just can imagine how, it’s raining, you’re soaking wet and you get cold, in that goddamn piece of steel. There was no fans even to take the goddamn...

Ruby Goldstein: You know what they had to do? We had a gun port on the loader’s side, see, here's you 75, you had your gunner, tank commander, your loader on this side, where he would throw a shell in the breech. On the left, right up here in the turret, there was a port hole, you open it up, push it out. You could get air. But what was happening in North Africa, they find out, at night, the Germans used to come up, you know it’s hot, you’ve got it open for air, they even dropped the hatch on the bottom to get some air. They’re scared to open up on the top. And they can’t throw a grenade if you had your 75 barrel elevated high enough; it’s not easy to put a grenade in. But that porthole was open, the pistol port; they'd throw a grenade in, everybody's lost. So the only way they could do it is tell them not to open it. Didn’t help. So they welded them shut. They had to weld them shut. Because too many were getting killed.

Tony D’Arpino: When they fired the big gun, when they fired the 75-millimeter, the smoke and everything else, you've got nothing to suck that out. Today everything is different, but they didn’t have none of that stuff. And them tanks were cold.

Ruby Goldstein: I had a pair of green knit gloves. And a leather glove over it. When I’d post the guard outside on the tanks, and it was cold, it was freezing. I had my boots and overshoes on top of the boots. It was so cold I used to take my gloves off and suck my fingers, I'd have the fingers in my mouth and suck them so that I wouldn't freeze. That's how cold it was. And you didn't stand. You were scared. You didn't know what to do. You know, as you stand still, you’re not moving. You’re not circulating. And if you moved, you didn’t know whether you should move or not, because your ears gotta be wide open to hear things. And if you were having perimeter, you have a section, you stay there, you don't go traveling because you’re gonna get killed, whether it was by friendly fire or enemy fire. So you stayed in that area. But it was cold.

Tony D’Arpino: I used to have a ritual when I was on guard duty. You’re scared, I don't give a goddamn what anybody says, I mean, you know, it’s one thing being scared and another being yellow. And you’re scared. And I used to have a ritual. I’d be alert, but it kind of occupied my mind. I’m the only boy in my family. I have five sisters, and so help me God as I'm sitting here, when I was on guard duty, I’d start with my oldest sister, and picture her in my mind, her name and everything else, then I’d go down to the next one, and the next one, and the next one, and the next one. And this kept me going. Then my mother and father. Then I’d think of my uncles. And by the time the two hours was up, you went through the whole family. But it kept your senses. It just helped me, that’s all I know.

Aaron Elson: Did you ever get frostbite?

Ruby Goldstein: A lot of guys did. I was lucky. When I was in the hospital, they had amputees, their toes, their feet, their fingers, their hands. All from frostbite. They turned green with gangrene; if you looked at it, sick looking, you wouldn’t believe it.

Tony D’Arpino: Then they gave us boots, remember them boots? We had them and the goddamn weather was getting hot and we still had boots. I couldn't even stand the smell; I took the goddamn things off once in a while, and the smell on my feet, I couldn’t stand it. I think I had two showers all the time I was over there.

Ruby Goldstein: Do you remember the time when we were in Normandy and we kept on going further and further, we had the same clothes. You didn't take them off; you couldn't wash. How did you shave? You shaved out of your helmet.

Tony D’Arpino: Your duffel bag was stored. You just had a few things in your Musetti bag.

Ruby Goldstein: Whatever you had with you. And when we finally got clothes, you had to disrobe; if you were near water of any kind, you’d wash yourself, and take your clothes, take the shovel, dig a hole and bury it. You’d get new clothes, but the old ones were so rotten, you could die from the odor. Listen, how long can you wear something? You know what I mean.

Tony D’Arpino: Your hair, we had these knit hats in the winter. Your hair, it hurt just to touch it, and the guys used to joke, “Well, I guess I’ll comb my hair,” and they'd take the hat and screw it around a couple of times, and it looked like they’d stuck their finger in a socket.

Loved the interviews; they are always unique.loved your book on the 712th Tank Batallion! A must for anyone reading WWII real life books!