Veterans Day, 2025

More of my conversation with Major Clegg "Doc" Caffery

Side 2

Doc Caffery: [Due to the flipping of the cassette, he’s talking here about placing tanks during the battle of Seves Island in Normandy, which, incidentally, is where my dad was wounded for the first time] ...the bridge over there, and I did. But I didn’t put them on the east side of the bridge. I put them on the west side, and General Patton comes along about five minutes later to check everything out and I reported to him very quickly, and the general looked at the tanks and he says, “Captain, get them goddamn tanks on the other side of the bridge!” (laughing) You know the little roadrunner that jumps up and digs his feet in the ground? I almost did that. That was my second visit with Patton. But he was a great guy, I tell you, Blood and Guts.

Clegg Caffery on General Patton:

-----

Aaron Elson: Oh, they found your luggage?

Doc Caffery: That’s my dogtag... One of my dogtags that I put there.

Aaron Elson: What does it say, let’s see, it’s got your serial number.

Doc Caffery: See, I put it together with a fishing (line), nobody could, yeah, “Clegg Caffery, 1354105, ‘42, AA blood, John Caffery my father, Franklin, Louisiana, and Protestant.

Aaron Elson: I’ll be. It’s got all that stuff? Now, why is it notched like that?

Doc Caffery: I think that’s from when they put it in the machine, to center the thing, to stamp that, I think that’s...So all the writing will be in the proper place.

Aaron Elson: Now where would you wear the dogtag? Around your neck?

Doc Caffery: Yes. And of course after the war, I said well, let’s use the old feller. I don’t know where this would be had I not had the dogtag. There it is right there. And you see, this is what I also do...

Aaron Elson: What’s that, USGA?

Doc Caffery: Yeah, I play golf. Aaron, I built a golf course one time.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Doc Caffery: Yeah.

Aaron Elson: Go on!

Doc Caffery: Sure. Well, now wait, I say built it, no, I was a prime mover in it. When I got home, I started to play golf, because there was nobody playing tennis anymore. So I was sitting in a barbershop one day and there comes in my good friend, who was named Earl Wilson, and he ran, he had the next-door, he was a sugar-cane farmer next to me, and he ran it for, his was a big operation. And we were sitting down, and I had just begun to play golf, a little bit. My wife played and so forth. I didn’t know much about golf, but I was sitting and talking to him, I said — his name was Earl Wilson — and I said, “Mr. Wilson, you play golf?”

And he says, “I used to play, and I like the game a lot.”

I said, “Mr. Wilson, you’ve got a place up there that’s crying to have a golf course built on it. There’s an old Victorian house up there, you’ve got about ten acres of cane that is terrible looking, and the tenants you’ve got aren’t doing a real good job.”

He said, “Tell you what you do. You meet me up there tomorrow and we’ll take a look at it.”

So I got my people who were interested in golf, and I’m an agronomist, my degree is in agronomy and I, you know, worked on a sugar cane farm, so anyhow, we went out there and met him and we talked to him. The cane crop part was terrible, because the four of us were, you know, not good farmers. He says, “I’ll tell you what I’ll do. If you buy these ten acres of cane, I’m gonna let you lease this property.” So we called our lawyers in, drew up a lease, we formed the Belleview Golf and Country Club, and everybody in town became very enthusiastic; golf at that time was just blossoming. So we had all the farmers got different pieces of equipment. I had a descending bulldozer that I made available. I had a land leveler. Joel Latham and his crew, he was in the paving business, and he lent us, oh, a whole bunch of equipment, a drag line to reset, one of the things in the sugar industry is what we call filter press mud, it’s a byproduct of what comes in with the sugar cane juice, in the form of dirt. And we put lime with it, to settle the juice out, so this lime comes in as an additive to the dirt that’s washed off in the cane field. And you get about, oh I guess you get a couple of hundred pounds of dirt, of this beautiful topsoil mixed with lime that’s been off out of the sugar mills when the sugar juice is clarified or purified or cleaned up. And this dirt is put in pits or stored away, it was sought after as a garden additive, you know, for vegetable gardens and so forth. So all the sugar mills had this. So I got a sample of the filter press mud and sand, and I sent it off to an agronomic laboratory and asked them to give me the proper formulation to make a golf green. So they sent it back and they said you use three parts of sand and one part of this beautiful filter press mud, mix it up and use that. So I got a drag line on the site, and got a few dump trucks, and went out and got this filter press mud. We ordered a couple of, I think two carloads of dysan(?), that we had a guy in the cement business, and I asked him what kind to get, he gave me that, we brought it down to the site, we mixed it. One of these guys had a little drag line, a half-yard drag line, we’d take three scoops of sand and one scoop of filter press mud, mix them up together, lay it out, put visqueen over it, and under the visqueen we shot...

Aaron Elson: What’s visqueen?

Doc Caffery: Visqueen is this thin clear plastic material. So we covered the sand, and the sand was about I guess three feet high and maybe fifty yards long or whatever. We covered the visqueen and put a fumigant, that, we used maybe a half a dozen or maybe a dozen cans of this fumigant to kill all the worms and also all the bad seed that was in this mixture. And we let it stay there a week or two, and then we took it off and cleaned it up, and spread it on the greens. And we spread it about that thick...

Aaron Elson: About a foot thick?

Doc Caffery: No, about eight inches thick. Six or eight inches thick, all over. And today they’re the best golf greens in the state. It’s noted, our little golf club, for having the best greens in the state. The greens are beautiful, you know. And I got to liking that kind of stuff. You know, because of my agronomic background. So we built the greens. We started building the greens in the spring and the following spring we played the first game of golf on the course, and three years later the Louisiana Open was held there. It was the only nine-hole golf course in the state that had that privilege. We had the Louisiana Open there. So anyhow, I was kind of proud of that fact (laughing).

Now, you may wonder what a story about building a golf course has to do with World War 2, but Doc, with his grounding in agronomy, no pun intended, was able to give me a pretty good explanation, in another interview, as to why nothing had grown for more than fifty years on the spot where Lieutenant Jim Flowers’ tank burned during the battle for Hill 122. Henri Levaufre, the late French historian, would often point out the patch of scorched earth when showing visitors the field in which Flowers’ platoon was ambushed.

“What is it that would make the earth around where Jim Flowers’ tanks were, what is it that would cause that not to let any grass grow, up to today?” I asked.

“I think the heat destroyed all the organic material to a certain depth,” he said. “When you heat it up, you sterilize it. That whole area was sterilized. That ground has been cooked, and all these nutrients have been cooked out and destroyed. Until that ground is turned up and fertilized and organic material is put in, it’s going to stay that way. Does that make sense? You’ve got to have three things necessary to make something grow. Nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium, those are the three elements that are necessary. And of course water, and sunlight. Of course you can grow things also hydroponically, but you’ve got to add the nutrients.”

“Henri is always asking people what happened, or what was in the tanks that would cause the ground not to produce,” I said.

“I think it was heat, but also the oil, that was also heated up and exhausted,” Doc said. You had a deep penetration in the ground, I would say five or six inches deep, would completely neutralize that area. And you don’t want to do anything to that area, because if you try to do anything it’ll come back lush, and you won’t have a story. So leave it there, it’ll last forever. I guess when a tank was hit all the diesel fuel went in the ground there.”

“Was there also antifreeze in the sponson?” I asked.

“There might have been,” Doc said.

“That’s what Jake Driskill said.” (Driskill, the maintenance sergeant, said that antifreeze was used to slow down the ammunition fire when a tank was hit.)

“I can’t answer that,” Doc said.

Incidentally, the Belleview Golf and Country Club in Franklin, Louisiana, is still going strong. It’s even got a Facebook page.

Now, back to side 2 of the original transcript.

Aaron Elson: You being in Headquarters Company...

Doc Caffery: See, that’s the problem, we didn’t have any commander...

Aaron Elson: But you remember that first day in combat, July 3rd, when the assault, when the 105 tank was hit? Did you have anything to do with that, going up to it?

Doc Caffery: You mean going into Perier? Is that...

Aaron Elson: I think so. When Howell was killed.

Doc Caffery: No. I wasn’t at that. You see, particularly at that point in time, everything was, oh Lord, you didn’t know what was going on. I will say this. I remember very distinctly going, all of us of the 712th went in to see the 90th Division commanding officer and he was telling us what he was going to do. And lo and behold, the headquarters people, me and others who were in headquarters of the battalion, they didn’t even think of us. They broke the battalion up right then and there and assigned these companies to different regiments, and that was it.

Aaron Elson: And they didn’t assign the headquarters anywhere?

Doc Caffery: No. They assigned A, B and C companies to the three regiments, and the D Company was on standby because of their 37-millimeter guns, you know, they were kind of light. At that point in time D Company was used in a flanking protection, but no direct contact.

Aaron Elson: But D Company lost some tanks too, the first day, didn’t they?

Doc Caffery: Yeah. You see, everything was helter-skelter confused; nobody really knew what was going on. Everybody was a little timid, you know. It was just the first time in action, you know, you don’t...

Aaron Elson: Now when you reported to the 90th headquarters...

Doc Caffery: It was General Landrum. He was the commanding officer of the 90th at that time. He didn’t impress me...

Aaron Elson: Is he one of the ones who was replaced and was not considered...[The 90th Infantry Division, which sustained the third highest number of casualties in the European Theater, had six different commanding officers between D-Day and VE-Day]

Doc Caffery: Yeah. Landrum was replaced, I guess within a week or two. I think so. It’s kind of hazy. As I remember, he didn’t stay around very long. [According to Wikipedia, he was replaced in August]

Aaron Elson: But did anyone, say, give you an idea of what you were in for, because they had been through some rough times?

Doc Caffery: No.

Aaron Elson: They didn’t say...

Doc Caffery: No, I don’t think they...Everybody was, you know, timid. It was, you know, the great unknown out there, you know, what the hell goes on. I mean, that was, you know, until you say “You do this thing, you do that that...” You don’t know what to do. I think that’s what I thought. Anyhow, we came back, and the companies were assigned to the different regiments. One was from the 82nd, I think. Nobody knew anything. It was all up in the air because it took a while to get your feet on the ground, to get acclimated or get unified, whatever you want to call it. I think we were lucky that we did what we did, and kind of went into it very carefully instead of not knowing what went on. I think those days you could say they were hectic because nobody knew anything about what was happening, you know. It was shocking to know that somebody was going to shoot at you (laughing). They were shooting at you, you know!

Aaron Elson: When you say shocking, did it make you angry? Did it make you scared?

Doc Caffery: A little of both, yeah. There was somebody shooting at me.

Aaron Elson: You must have seen...

Doc Caffery: I didn’t see any casualties, no. Not right away. As I was going I was seeing this guy up on a fencepost, wait, let me see now, where was I? I did see a, I think this may have been a German, his body was on top of a fencepost...

Aaron Elson: As if someone had put it there?

Doc Caffery: I don’t know whether, he might have tried to jump over the fencepost and been shot in the process. But to see that guy right there was a...

Aaron Elson: So it must have...What did it look like?

Doc Caffery: Kind of shocking, to see a goddamn...It can happen to me. I think the first few days of battle were very, what’s the word now, very indecisive, I guess that would be it. Nobody knew what to do, and so consequently nothing much was done. I think that was it, until...

Aaron Elson: Do you remember Lieutenant Duval?

Doc Caffery: Oh yeah, Henry Duval, yeah.

Aaron Elson: Now Duval, how did he get the French derivation for his name?

Doc Caffery: I think his family was Duval, was French.

Aaron Elson: So did you talk to him or know him because of your Louisiana...

Doc Caffery: No, no, because he wasn’t from Louisiana, he was from up, I think in the northern reaches of the country. I think so. He wasn’t a Southerner. He might have come from a Canadian border, somewhere up in there. Henry Duval.

Aaron Elson: What was he like? [Here I guess I’m trying to get some insight into some of the battalion members about whom I’ve heard. Lieutenant Duval led the second platoon of C Company. He was wounded on July 7, 1944, and didn’t return. Lieutenant Leo Hellman led the third platoon and was relieved due to combat fatigue.]

Doc Caffery: He was a good little guy. There was nothing wrong with him.

Aaron Elson: He was badly wounded, wasn’t he?

Doc Caffery: As far as I know, yeah, early on. He got kind of beat up. But you know, you can’t say a good guy, because at that point in time nobody was...

Aaron Elson: How about Hellman, did you have any contact with him?

Doc Caffery: I saw Hellman, yeah, I saw Hellman, Hellman was a good guy. I liked Hellman. I saw him when he first got into combat, not at the Falaise, was it along the Saar?

Aaron Elson: Before. He was relieved at the Falaise.

Doc Caffery: He was relieved at the Falaise, okay, I remember. He was timid, I think. I don’t know the, I know he was relieved but I don’t know the incident and I remember him as being a very pleasant guy, but very timid. He might have been afraid, I don’t know, but I don’t think that, that’s how he came across to me anyway. But my, again, my position, you know, I wasn’t in command of anything, see I was an S-2, S-3 and XO [executive officer].

Aaron Elson: What about that trip that you and Forrest [Dixon] took back to get the ammunition...

Doc Caffery: (laughing) Oh yeah, me and Forrest, yeah. Oh, Lord (laughing). We went back to lead the train forward, Forrest and I.

[Following is Forrest Dixon’s account of this incident, from my book “Tanks for the Memories”:

Forrest Dixon

When they made this advance toward Le Mans, they left half the trains back in Mayenne. The trains had ammunition and gasoline. Well, we got into a little firefight on the way, and we were using more gas and ammunition than we thought.

Colonel Randolph and General Weaver called me over, and Colonel Randolph said, “Captain Dixon, you and Major Caffery go back to Mayenne and get the trains.”

I couldn’t understand why he wanted me up there, but I thought, well, I originally was a tanker, maybe he’s going to give us a few light tanks or something. It was midnight, and we had to go through sixty kilometers of no man’s land.

“Yes Sir,” I said. “What are we going to take back for protection?”

“Oh, I think you and Major Caffery would be better alone.” So all we had was a jeep.

The most eerie part of that was Colonel Randolph and General Weaver held out their hands, and General Weaver said, “Hope to see you tomorrow.”

I sure hoped so! That’s the first time I ever shook hands with a general. “Hope to see you tomorrow, boys.”

Aaron Elson: Now when you say trains, were these trucks?

Doc Caffery: Well, they call them trains, but it was the support trucks, gasoline and all the support vehicles, the kitchens maybe or whatever, that was back in the rear waiting for the time to come forward. And so we went to pick them up, particularly gas. That was a ride, gee whiz, Forrest and I. We thought that the Germans were gonna come in on us, you know. You know, you get these ideas that the first people you’re gonna see are Germans, but that wasn’t the case, because the Germans were, they didn’t know where to go themselves.

Aaron Elson: But you were in no man’s land, right?

Doc Caffery: We were in no man’s land, yeah. I didn’t have any qualms, I didn’t think of being hit or being shot at, because we had just been that way. I think that anybody we saw back there would be just as afraid of us as we were of them, because the Germans were demoralized at that point in time. So we went back to get the trains. I wasn’t thinking of running into any opposition.

Aaron Elson: Who was driving?

Doc Caffery: Blessing was driving, I think it was Blessing.

Aaron Elson: And the two of you were in the back?

Doc Caffery: I think Forrest was in the back and I was in front. And I believe I stood up for a while and he was sitting in the front, we kind of changed around.

Aaron Elson: What about when you picked up the Free French? He said you picked up some FFI? [Free French of the Interior]

Doc Caffery: Yeah, you know, I didn’t think anything of that. I just took it as, they were walking along the road, I just thought we’d give them a hand, it didn’t enter my mind, what are we gonna do now.

Aaron Elson: Did they have uniforms?

Doc Caffery: No, they may have had a little beret or something that might have indicated, but as I remember, it wasn’t a big deal for me, I didn’t think of it one way or another. But I’ll tell you this incident, we were coming from Avranches, going eastward, and I was in the headquarters company halftrack, and we came, as we went over this hill and came down, there was a German antitank gun that fired on us. And, let’s see, there were me and Jack Roland and Beverly Simms and Basil Zimmer, all the Headquarters Company people were in that halftrack, and you know, all of them got hit except me and the driver. The driver was there, and I was right next to him, standing, and everyone got hit but us two. We went across the road, everybody got out. Beverly Simms and I, who I loved and I was kidding him all the time. By the way, he ended up being the law clerk for Jimmy Burns. A nice fellow, from South Carolina.

Aaron Elson: Wait, who was Jimmy Burns?

Doc Caffery: He was a senator, from...and later on a Supreme Court justice. Does that ring a bell? I think it’s Carolina. Anyhow, Beverly was later his law clerk. Anyhow, so Beverly and I dove over in the bushes there, let’s see, everyone that was wounded, my S-2 sergeant, he jumped out, got hit in the leg, I mean my S-3 sergeant, a nice guy, Greely, Sergeant Greely jumped out, and got hit in the leg. Beverly Simms got out, we jumped out together, Beverly got hit in the arm, and says “I’m hit!” And I looked at him, “You sonofabitch, you ain’t no such thing!”

Aaron Elson: You said that?

Doc Caffery: I did, I cursed him out.

Aaron Elson: How come?

Doc Caffery: I don’t know, I guess, he and I were always playing together...

Aaron Elson: But you knew he was hit, right?

Doc Caffery: Oh yeah, he said “I’m hit, in my arm!” I said, “Beverly, you’re full of shit.” Anyhow...

Aaron Elson: What about Roland?

Doc Caffery: He was hit, too. He was evacuated. And Greely was evacuated. So there were, let me see, yeah, everyone got hit. Beverly was superficially, it drew blood, I mean that’s about it. Greely came back and lost his leg. I think it was a tourniquet job, though. We gave him a tourniquet and didn’t relieve it. About maybe twenty minutes we walked back on the road. But that brought me to attention right quick, you know? To be shot at. If I knew where it’s coming from, you know, you get shot...

Aaron Elson: You didn’t know where it was coming from?

Doc Caffery: No, we didn’t.

Aaron Elson: And the people who were wounded, were they wounded when it was hit, or getting out?

Doc Caffery: When it was hit. During the episode, I think they may have dropped a few more shells in the area. But it was an antitank gun that was maybe four or five, or maybe a thousand yards away that was zeroed in on the crown coming over there, as soon as we came over it let loose at us.

Aaron Elson: Now tell me, I’ve heard this term three times, and the first two times I had no idea what they were talking about, you just mentioned it the third time, a crown in the road. What’s...

Doc Caffery: Okay. When a hill comes down, the road was going up, you see, and then the hill comes down, well, we call that the crown when the road changes direction over the hill.

Aaron Elson: Okay. And that’s because the roads were...

Doc Caffery: Well, it was going up and coming down. So you were coming up on one side, and the crown is at the top and you’re going to go over the crown, going down. So when we came over the crown, that’s when we got hit.

Aaron Elson: Were there a lot of roads like that?

Doc Caffery: Well, in that area, because it was kind of hilly. Wherever you have a hill, the road goes up, this is what I always called it, having a crown. You have crowns all over.

Aaron Elson: Because I’ve heard, I guess it was Judd Wiley said that in Normandy the roads had a lot of crowns.

Doc Caffery: Oh, yes, the roads went up and then came down. It was kind of slow like, it wasn’t steep. It was an easy, flowing road. So anyhow, that was my...That was really my introduction to being shot at.

Aaron Elson: Were you scared?

Doc Caffery: No, I wasn’t scared. I don’t think, I didn’t realize at the time, I don’t think you were scared unless you think about the circumstances. I wasn’t thinking about the circumstances, in fact, when I cussed old Beverly out, I didn’t cuss him out, I was kidding him, “You ain’t hit, goddamn, get up.”

Aaron Elson: What was England like?

Doc Caffery: The country? Oh, I loved England. I thought it was delightful.

Aaron Elson: Did you have much contact with people in the towns?

Doc Caffery: Not that much, no. I think we had dances, and we saw some WACs.

Aaron Elson: Did anybody have English girlfriends?

Doc Caffery: I think they, I didn’t have any, but I knew that there were a lot of, some of the boys, particularly after the war, when we were out in the, when we came back to...

Aaron Elson: To Amberg?

Doc Caffery: Amberg, everybody had their, that’s where everybody went into, there were, Edward Hoffman, you know, went into. That was at Ste. Marie aux Chenes, when we were going forward, when our battalion CP was in Ste. Marie aux Chenes.

Aaron Elson: That was the baker?

Doc Caffery: That was the baker. I had him over here, he came to my house, because we stayed there I guess maybe two weeks, so he invited me to dinner with him. I think about two Sundays, he invited me to dinner. I liked him, you see, I’ve got French blood in me. My mother was a Frere. So here, I’m sympathetic for the French, I tried to talk French and I do talk a little patois, and being, South Louisiana being French.

Aaron Elson: What did your father do?

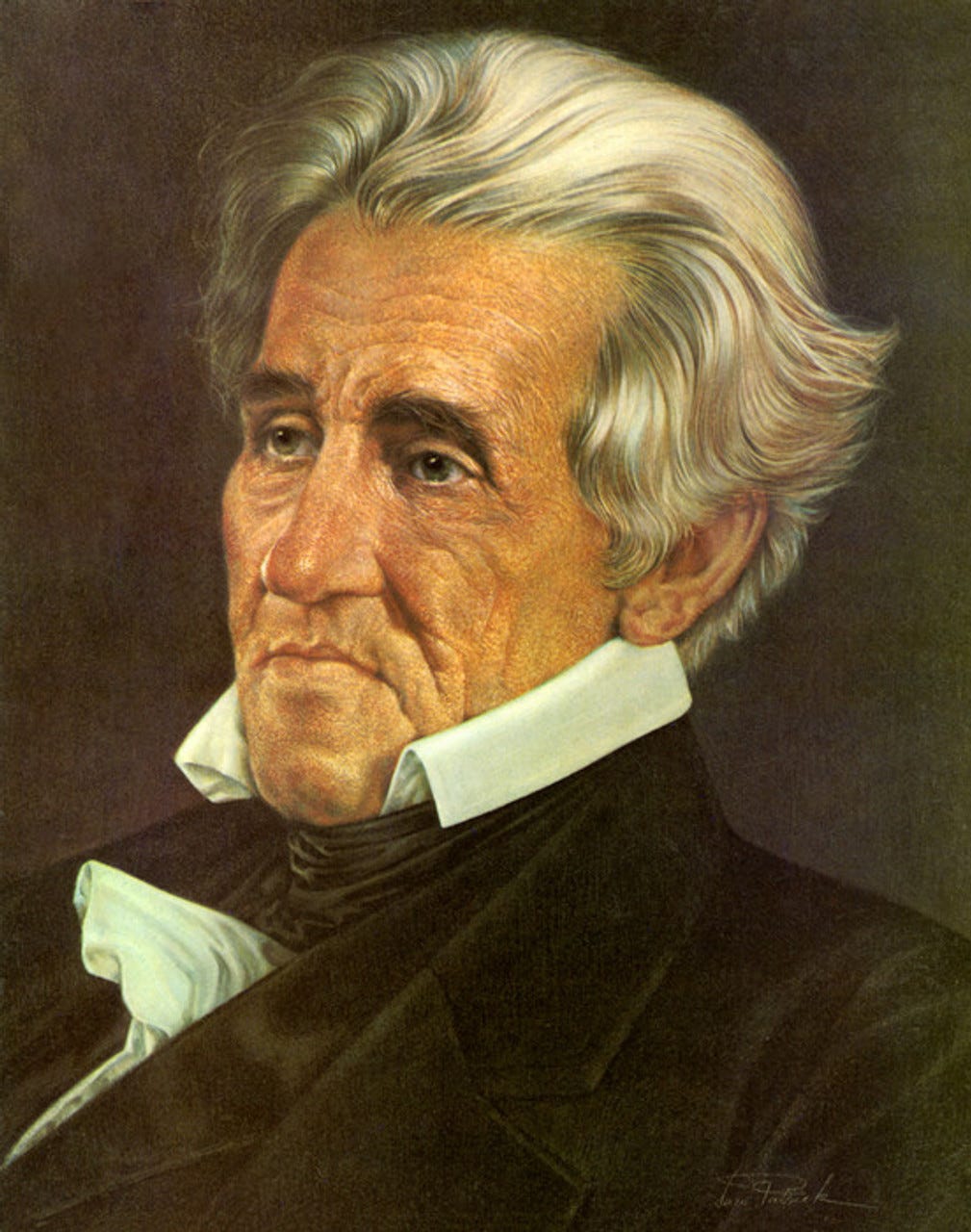

Doc Caffery: Okay, my father -- well, I’ll go a little bit further back. There’s a fellow by the name of John Caffery who married a Donaldson. Andrew Jackson was his brother-in-law; he married his other sister.

Aaron Elson: Go on! Andrew Jackson?! Now your grandfather...

Doc Caffery: My great-grandfather married, let me see, Andrew Jackson married Mary, no Rachel, and my grandfather married Mary, her sister. That’s how we...And they came down the Cumberland together, these two, Andrew Jackson and the Adventure down the...In fact, my grandfather, they were captured by the Indians, they were captured for a year or two...

Aaron Elson: Really?!

Doc Caffery: Yeah. That was kind of desolate up there on the Cumberland.

Aaron Elson: The Cumberland River?

Doc Caffery: Yeah, the Cumberland River, or the Tennessee, which was it? One of those. Anyhow, they came down both.

Aaron Elson: So your grandfather was captured by the Indians?

Doc Caffery: His wife, too, they were captured I think for about a year.

Aaron Elson: And then how were they released?

Doc Caffery: I don’t know, it was in this book, oh I don’t know, I’ve got the book at home, it’s been so long ago, but that’s my background. See, my father went to Annapolis, and his classmate and roommate was Admiral King, the commanding officer of the fleet. So I was a military background...

Aaron Elson: So your father was in the Navy?

Doc Caffery: Yeah, he graduated, he was in the, he and Admiral King graduated from Annapolis together. They were roommates. E.J. King.

Aaron Elson: And King was commander of which fleet?

Doc Caffery: He was the commander of the whole shebang. I think he was.

Aaron Elson: Was your father in World War I?

Doc Caffery: Yeah. He was in command of the naval station in New Orleans in World War I.

Aaron Elson: So if he was in the Navy, how come you wanted to be a flyer?

Doc Caffery: I don’t know, that was something, I don’t know about that. It was a spur of the moment thing.

Aaron Elson: Had you been drinking?

Doc Caffery: No, I just thought I wanted, I’d like to fly, you know. ‘Cause I was out there, I was stationed at Randolph before the war, and all these flyboys come around. When I went in later on, I thought I’d like to fly. But when it came to flying, being a flyboy’s not my cup of tea, I just didn’t particularly care for it.

I’m glad I had enough, not enough guts or, I’m glad I got out, because hell, I got right in the 712th Tank Battalion, what could you ask could be better?

Aaron Elson: Did you enlist, or were you drafted?

Doc Caffery: I was a Thompsonite officer early on.

Aaron Elson: You were what?

Doc Caffery: What they call a Thompsonite officer.

Aaron Elson: What’s that?

Doc Caffery: Way back there they put a thousand ROTC graduates on active duty for one year, and they picked out the top hundred. I went in the service for one year, but I wasn’t one of the lucky hundred, to be commissioned. So I went back to LSU to get a master’s. In sugar cane. I had it all set up, I was gonna plant sugar cane at various times of the year to see...But I got through that and I said, “No, I’m gonna go back into the service.” So I asked to go back in. At that time, they were taking all the volunteers, so I went back in, and that’s when I got to know General Newgarden, because I washed out of the Air Force, they sent me to Randolph [Benning] and I was in charge of the paratroopers and I was playing tennis with John Wood and Paul Newgarden...

Aaron Elson: Who was John Wood?

Doc Caffery: He was General John Wood. He had the 4th Armored Division. Later on. I think he and, General Wood was a big, heavyset guy, gruff, nice guy. I think he and Newgarden were classmates.

Aaron Elson: Newgarden was West Point?

Doc Caffery: Oh, yes. He was a West Pointer.

Aaron Elson: And Chamberlain...

Doc Caffery: Chamberlain was a sonofabitch.

Aaron Elson: Was he really?

Doc Caffery: Oh, Lord, yeah.

Aaron Elson: He was cavalry, wasn’t he?

Doc Caffery: Yeah. He was an egotistical guy. I didn’t like him. Now maybe I didn’t like him because I didn’t like his, I didn’t like Chamberlain, he was regular Army. Yeah. He kind of looked down at you, kind of snotty like. He didn’t have a pleasing personality, you know, to be a leader you’ve got to, well, I guess a leader is maybe taking care of the other people around you. I think that goes a long way when your guy’s looking out for people under him, because they’re gonna look out after him. But Chamberlain was a, I just didn’t warm up to him. He just didn’t, was kind of cold, with the idea of I’m Chamberlain and you ain’t worth two bits. I think that’s the attitude.

But Whitside Miller was a disaster. Ohhh. That’s when I joined, you see, I was in the battalion at Benning. Baxter Davis and I and Whitside Miller.

Aaron Elson: Now Baxter Davis was the exec...

Doc Caffery: Yes, he was the executive officer early on...

Aaron Elson: And you were what?

Doc Caffery: Well, I had a company, then they brought me up to battalion. I was S-2, S-3, and then later on, when [Vladimir] Kedrovsky came in, they made him, later on they give him, Kedrovsky was a good guy, very affable, very smart, very smart. And very, well he looked after Kedrovsky pretty good. Did you get that?

Aaron Elson: Which?

Doc Caffery: That Kedrovsky was looking out after himself. That’s what I thought. Am I saying something that you have heard before?

Aaron Elson: No, I haven’t heard much about the officers.

Doc Caffery: Kedrovsky was a good guy, but he was looking out after No. 1. Big time.

Aaron Elson: Wasn’t there a rivalry between Kedrovsky and Les O’Riley?

Doc Caffery: Not that I know of. But Kedrovsky was one who wouldn’t give you, he and I got along well, I think you could say that. In fact, they picked Kedrovsky to command the battalion over me.

Aaron Elson: Over you? [Thirty years later, this is the first I’m realizing that after Colonel George Randolph was killed during the Battle of the Bulge, Clegg Caffery, who then likely was the battalion executive officer, might have been picked to lead the battalion.]

Doc Caffery: Yeah. Which was all right. I mean, that’s part of the game, you know. If they had picked that guy, I wasn’t put out, upset about it. I said, well, if they think that, well good, I’ll try to do better.

Aaron Elson: And what was Kedrovsky at the time? Was he the executive officer?

Doc Caffery: Kadrosky came up very fast. First lieutenant. Second lieutenant, I mean then a major right quick. Kedrovsky was very smart. I outranked him, I just didn’t, you know, you can’t cut the mustard, you can’t force somebody else to take...And I think, when I look back on it, at that point in time I was a kind of timid guy, you know, and you don’t need a timid guy to lead a...I think I could have, but that’s hindsight now. No, we had a good bunch of boys. We had an excellent bunch of guys in the 712th Tank Battalion. After we got rid of Whitside. Baxter Davis was an excellent guy.

Aaron Elson: How come Baxter Davis left?

Doc Caffery: I think when they sent down this team from General Middleton, you see, he sent the team down, and he interviewed all the officers, this team did, and I think he even decided that Baxter’d better leave also, because there was a lot of friction between Baxter and Whitside. So Baxter was relieved too at that time, but not in the manner that Whitside was. Baxter was kicked up and went to, there was a tank group that Baxter was assigned to, and the tank group was in charge of several battalions of tanks, and I think that was a reservoir for officers if they needed them. So Baxter went up there.

Aaron Elson: Did he wind up going overseas?

Doc Caffery: Oh yeah, he was overseas at that time.

Aaron Elson: Oh, that was in England, oh right, yes.

Doc Caffery: Baxter was a good ol’ country boy from Georgia. I think he went to Clemson, or the Citadel or something like that. Baxter Davis was a good man. He tried to do his damnedest. Whitside, he was the executive officer, and Whitside made him doubletime in front of the whole battalion one morning.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Doc Caffery: Suuuure.

Aaron Elson: I mean I heard that, but what...

Doc Caffery: Sure he did, sure, Whitside, (shouting) “Come here, Major Davis! On the double!”

Aaron Elson: Was there any one specific thing that made him do that?

Doc Caffery: Whitside?

Aaron Elson: Yeah, that made him...

Doc Caffery: No, I think that Whitside was beginning to feel the pressure, and he couldn’t cut the mustard. I think that was in the back of his mind.

Aaron Elson: What was this about Whitside and Patton’s daughter?

Doc Caffery: Well, Whitside you see was an old Army man. He came from way back there. There’s a Whitside, Camp Whitside or Fort Whitside out in the West somewhere.

Aaron Elson: Somebody said his grandfather...

Doc Caffery: He was in, I know he was in the Army, I think he was a colonel or something...

Aaron Elson: Someone said that one of his ancestors was at Wounded Knee...

Doc Caffery: Could have been, because I heard that, I heard something of that. I don’t know, I’ve heard it just like you’re saying it now. But Whitside was, Whitside was stupid. But he was regular Army, you see. And Dixon was responsible for this, you know.

Aaron Elson: Was what?

Doc Caffery: Dixon is responsible. You’ve heard, Dixon has told you, you’ve got it on tape I guess.

(It was Major (then Captain) Forrest Dixon who instigated the letter writing campaign that got Colonel Whitside Miller replaced.)

end of tape