A few Substacks ago, I mentioned that the German historian Walter Hassenpflug was instrumental in identifying the pilot who caused the explosion of April 3, 1945, in which Ed Forrest, Dorothy Cooney’s boyfriend, was killed, and wrote “but that’s another story.” In case you missed it, here’s a link to the original post. Now here’s the other story.

A few months after my visit to Heimboldshausen in 1999, Walter sent me the following article.

Pilot Identified After 54 Years

The last victim of the Inferno

Today it is exactly 54 years that, after the raid on the Heimboldshausen Train Station, a Messerschmitt 109 crashed. The origin of the unidentified airman who was buried at the Roehrigshof cemetery has only now been clarified.

By Kurt Hornickel

Staff writer

BAD HERSFELD – “You have to clear this up. I have to clear up the fate of this soldier in the middle of Germany. Maybe there are still some relatives alive.” This thought has incessantly been moving Walter Hassenpflug of Friedlos for the past years. As a researcher of the aerial warfare in the local area, he has done a detective’s job since 1986 in order to close the last chapter of the grave air raid on the Heimboldshausen train station. Eight apartment houses and six farm buildings on Bahnhofstrasse were reduced to rubble and ashes while American forces were already advancing into Thuringia via Vacha and Unterbreizbach.

More than half a century ago, the remains of the German flier, who was killed on 3 April 1945 during a raid on Heimboldshausen, which was then occupied by the Americans, were laid to rest at the Roehrigshof cemetery.

Vague clues

It had not been possible so far to establish his identity. Even an exhumation, which was initiated by the People’s League of the German War Graves Commission in February of 1964, did not shed any light on the identity. At that time, it was only determined that the man had been 173 cm tall, and his age was estimated at 30 to 40 years. Parts of the collar patch of the blue/gray uniform simply hinted at the fact that the rank of the pilot was somewhere between A1C and Senior Master Sergeant. Items of personal belongings were not found, and his “dog tags” were never found either.

Now, with Walter Hassenpflug’s assistance, the family was officially informed of the airman’s fate. He is, without any doubt, the then 28 year old Tech Sergeant Erwin Bunk, who was born in Silesia on 24 February 1917. The young man, a watchmaker by profession, had just been married and was the father of a one-year-old daughter. His wife, Eva Maria, was then 22 years old and is now living with her married daughter in the Ruhr Industrial District. The family had never given up their search for the missing airman. Mrs. Bunk also never remarried.

For more than 50 years, Elly Saam, nee Metz, of Roehrigshof has been taking care of the grave of the unknown soldier. Mrs. Saam, whose brother, also an airman, got killed during the war had personally witnessed the plane crash from only a short distance away. After the crash, She secured a portion of a torn-off propeller of the fighter plane and made sure that it was placed on the grave of the unidentified pilot as a tombstone. It is due to Walter Hassenpflug’s diligent research and far-reaching contacts that, after so many years, the fate of a missing person in the middle of Germany was able to be cleared up.

After Hassenpflug, four years ago, had been able to clear up the fate of the then 21 year old Lieutenant Paul Kolster in a side-valley near Unterneurode, he again was assisted by the private Missing Person Tracing Service of Herbert Bethke and Friedhelm Henning of Lower Saxony.

These private persons, who are searching all areas where downed airplanes are expected to be buried in the ground, were in fact able to get Walter Hassenpflug in touch with the second pilot involved in the raid that took place in the afternoon of 3 April 1945 when two German [air] planes during an attack on Heimboldshausen train station blew up a freight train loaded with ammunition and fuel: Tech. Sergeant Willi Tiedtke, who is now a retired police officer living in the vicinity of Paderborn, was the pilot of the Me 109 who escaped the inferno after the raid on the freight train. Walter Hassenpflug is in possession of a written statement of this pilot which finally does away with the speculation that bombs were used in the raid. Tiedtke’s statement plus the local facts made authorities become certain of who the pilot was who crashed into the apartment house of Theodor Piontek at Roehrigshof with the wreck of his airplane.

As a member of Group IV of Fighter Wing 301, Sergeant Willi Tiedtke, together with his squadron comrade Erwin Bunk, had taken of from the Hagenow Airfield in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern on 3 April 1945 – the Tuesday after Easter – in order to destroy a Wehrmacht train hauling fuel between Bebra and Eisenach. This train had ended up in the front lines of the fast advancing Americans and was now evidently stuck at the Heimboldshausen train station.

At this time, the fight between the Armed SS and units of the 90th US Infantry Division was over, the battle had been fought, the village was severely damaged and occupied. Heimboldshausen had been hit hard by artillery and tank fire on the Saturday before Easter. Several homes and barns were destroyed or on fire. Six civilians were killed.

Flying low from a northerly direction, Tiedtke and Bunk were strafing the freight train. There was a tremendous explosion with a column of fire rising in the air for several hundred meters. Tiedtke fully opened the throttle and flew over the wall of fire. He then noticed that the plane of his buddy Bunk was coming out of the ball of fire burning, and saw it crash next to the end of the train station. As a result of this air raid six residents were killed.

Due to the confusion of the last days of the war, the widow never received the letter of the Squadron Commander describing the circumstances and location of the death of Erwin Bunk.

Walter Hassenpflug has compiled a lot of statements and eyewitness reports, even from American sources, and put the jigsaw puzzle of this war drama together in a documentary.

Hassenpflug’s tracing started systematically. Since there was conflicting information regarding the type of airplane, Walter Hassenpflug took the propeller blade off the grave and had it examined. As a result of the examination, it became certain that the downed airplane was not, as initially assumed, a Fokke-Wulff but an ME-109. As a result of the war events, a total of 30 buildings were totally destroyed at Heimboldshausen, 37 were severely damaged, and 63 received minor damages.

So there you have it. This is why I have never attempted to write historical fiction. Eddie Forrest’s girlfriend, Dot Cooney, never married; Luftwaffe pilot Erwin Bunk’s young bride never remarried and her 1-year-old daughter grew up without a father. A nonfiction story with a thousand iterations, and even a few in my minuscule (compared to, say, the Veterans History Project) archive of interviews.

The article also corrects one of the things I have always said about the explosion. While most books about the 90th Infantry Division that address this event attribute the explosion to a bomb dropped on a carload of black powder — the article does mention that the train was carrying fuel and ammunition — it was not a bomb but rather strafing by the two attacking German planes (or possibly the American servicemen firing anything that would shoot at them). But one of the two German historians (not Walter, and I’ve forgotten the name of the other; I should have kept better notes, in fact I don’t think I took notes at all) said that the two fuel tanker cars were empty but were filled with fumes, which immediately brought to mind the explosion of TWA Flight 800, which was attributed to a spark igniting fumes in the empty center fuel tank, although initial theories had it being accidentally shot down by some sort of missile). According to the article about Erwin Bunk, in which the second pilot witnessed a fireball, the fuel cars may indeed have not been empty — which begs the question of why the truck with 300 jerry cans of gasoline parked outside Ed Forrest’s headquarters did not explode. Damned if I don’t wish I paid better attention in chemistry and physics in high school, could it be that the gasoline was protected by the jerry cans?

I do remember Walter saying the second pilot was so disgusted by the war that he at first refused to speak, but eventually provided his description of the attack.

Because it was Walter who introduced me to the story of the ill-fated Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944, which I would become involved in documenting the accounts of numerous survivors, Jim Bertram, the president of the Kassel Mission Historical Society, asked me how I met Walter. Now that’s a story in itself.

As I recorded accounts of the explosion at Heimboldshausen, I heard conflicting descriptions of the attack. Some tankers who were there said it was a lone German fighter. Other tankers said it was two German fighters. Gasoline truck driver Joe Fetsch, who was seriously wounded in the explosion, said a German fighter plane had been pestering them all day and he almost had a shot at it earlier but his assistant driver messed up his aim. And then there was this: The 90th Infantry Division veteran who asked me how to correct an error that he read in a book — he was referring to John Colby’s “War From the Ground Up,” which attributed the explosion to a bomb striking the carload of black powder — added yet another conflicting eyewitness account.

Ted Hofmeister: I was about 200 yards away, and I saw the German plane go out of control. He hit a house about four or five miles up the road. And we left town because it was smashed, the whole town was smashed. And as we were leaving we saw the German 109 up against the side of a building, smashed.

I was in headquarters company of the 358. I heard the planes. There were two. A P-51 chasing an Me-109.

(Now I’m thinking whoa, Nellie! An American plane was chasing the German plane?)

Ted Hofmeister: I saw the explosion. Half of the sky was red. The railroad station was flattened. There wasn’t anything left of it. The buildings across the road from it were occupied by Germans, and I don’t know how many of them were killed. And a whole bunch of us went up there and started rescuing these people. They were buried under rubble. And when we got up there, we saw an old man, I say old man, he’s probably younger than I am now, and he was trying to lever up a staircase that had fallen on his wife’s legs. And he had a timber that was eight or nine feet long and he was trying to do it, but he wasn’t strong enough. So about four big guys took hold of the timber and they pried it up, and when they did another fellow and I reached in and grabbed her under the armpits and pulled her out. And while we were doing this she was praying in German and telling us what good soldiers we were and she kept patting me on the arm. It wasn’t until later I found out the whole sleeve of my field jacket was bloody, because she had cuts all over. We rescued her, they got her on a litter and took her away, and we went on to the next building, and it was occupied by about three families. And the first thing we discovered when we went in, there was a landing, and there was an old lady, maybe 80 years old, she was about half buried in the rubble, and all that was sticking up was her arm and one side of her face. And her arm was going like this (up and down and twitching), spasms. And we dug her out, put her on a litter. I have an idea she died. We went up to the next door and a woman came running up to us and she started talking in German, which I can understand a little bit, and she said something about her baby, it had been blown out of her arms. We looked all over for that child and couldn’t find it. We figured it had been blown out the window and been buried under the rubble. And we rescued about, oh, I’d say about 10 kids. I particularly remember one boy, about 12 years old, he had his nose pushed way over to one side of his face, he had a broken arm, all cut up. All the people were cut up. And we went on to another building to see what we could do, and about that time one of the men from our company ran up and said we were evacuating the town because it was so shattered, and so we loaded up, and that was the last I saw of it.

Aaron Elson: How many men were in the rescue party?

Ted Hofmeister: Oh, I’d say about 30 of us.

About five minutes after the explosion, one of our fellows, a big Swede, he took his helmet off and was wiping his forehead, and when he did the tiles fell from a roof and hit him on the head and knocked him out. We had I’d say roughly 60 men, not of our company, but from different companies, about 60 men were injured.

I didn’t even remember that the tankers were in the town. All I remembered was that the 358th Infantry was in there.

I don’t know that anybody in our company got killed. I know quite a few got injured. As a matter of fact one fellow, even after the war was over, from occupation duty, it was about three months after this, and they were still picking glass out of his face.

Now, about that baby that may have been blown out of its mother’s arms. Dick Bengoechea was a first-time attendee at the battalion’s 1995 reunion in Louisville, Kentucky. He showed up with a blown-up picture of one of the houses in Heimboldshausen, with a cut-out of a gasoline truck outside (I do not have a copy of the photo with the cutout). I also never got a chance to interview Fred Hostler, who lived in Pennsylvania.

Aaron Elson: Now where did you get that picture?

Dick Bengoechea: They had a small photo, a guy by the name of Roland took that picture, and I guess the battalion or the Army wanted a picture of it, because it was a carload of black powder, or two, whatever. ... You can see there’s a doorway down in there, that's where Forrest got it, I guess. And these are Germans cleaning up afterwards.

Aaron Elson: So that’s the next day when they were digging it out?

Dick Bengoechea: Well, I don’t know. I was long gone. I was probably back in a hospital in Darmstadt. But right here, where that X is, that’s where that Fetsch was there for two and a half days and he was unconscious for 22. They didn’t find him. He was buried under all this shit.

Aaron Elson: Is that so?

Dick Bengoechea: Yes. That’s Fetsch.

Aaron Elson: He makes a joke of it.

Dick Bengoechea: Well, you know, what is there you can do about it afterwards?

Aaron Elson: What he said in seriousness was that a beam was under his legs, and had...

Dick Bengoechea: See, there's a street around here, and these Germans are apparently picking up, I don’t know how many days. Now, this was his gas truck [pointing to an illustration of a type of truck], and he was driving, and it was backed right in here beside these buildings...

Aaron Elson: Now, that is his truck, or a model of his truck?

Dick Bengoechea: Well, I cut that off and put it on there. Okay. Now this is a model of a truck. And it was loaded with 300 or 250 cans of gas. So, that day, our tank was broke down and was in ordnance, so we were back with the company, the platoon. So this gun on his truck, the rollers was rusted, it wouldn’t roll. So I had a can of oil, I was standing on this running board, and a guy by the name of Fred Hostler was up in there, and the ironic thing, the day before, why, a Kraut plane was flying around, and of course when one goes around, everybody wants to get a shot at a plane, and so we was working on that [the rollers] and then I turn around and look right up this valley, and it's just like in the movies, this plane was coming in, I could see the bullets coming down. And I don't remember, from this point, I woke up under there pinned under all kinds of shit like this and I couldn't get out.

Aaron Elson: Under the truck?

Dick Bengoechea: Under the truck, and I don't remember...

Aaron Elson: Under the gasoline truck? Jesus!

Dick Bengoechea: Well, that’s something I finally figured out in this last two or three months. See, I never knew any of this till about three months ago. And I was pinned under there. Well, this kid [Hostler], apparently, somehow, either blowed out or got out, and in this house on this side was a window, with glass in it, and it exploded. It just blew, cut him, he couldn't see worth nothing, just like a meat grinder. I’ve never found him since, he’s in Pennsylvania, but he’s never responded, and when we ran into each other in Paris, oh, a few days after that in the general hospital there, the only remark he made, he said, “That little girl blew up.”

Aaron Elson: What? That little girl?

Dick Bengoechea: Yeah. There was a little girl standing in that window. He was gonna dive into that building, see, from this side of the truck which was backed into this. And it had to be the concussion. Because the concussion was so great, see, these buildings here, now this building over here, that's the way concussion works; you can be on one side, it'll stand, and the other side don’t. This building was a lot taller than these, and see how that's leveled.

Aaron Elson: So he said there was a little girl in the window and she blew up?

Dick Bengoechea: Yeah, that's all he ever said. And I thought, well, maybe he's a little rummy yet.

Aaron Elson: Did you see a little girl?

Dick Bengoechea: No, because I was on this side. And I don’t know how I got from this point to that point. But I woke up, I couldn’t get loose. So I hollered, and he come over, he crawled over there, and he couldn’t see, and rubbed the stuff off of me, got me out of there. Then somebody said the aid station is up here.

Aaron Elson: Up to the right.

Dick Bengoechea: So he drug me. I guided him, he drug me up to the aid station. They gave me morphine from there till the next, I don't know a shittin’ thing until the next morning, I woke up when an American nurse in a field hospital said, “Wake up. We're sending you to Darmstadt and then you're gonna fly to Paris.” In a C-47. And there was a Purple Heart pinned on the pillow with the citation, a piece of paper, I've still got it, about this long, on my pillow. Then they give me another shot and I woke up the next day in a Paris hospital. And it was a day or so after that I ran into him [Hostler]. We was both in wheelchairs, and he was going down the hall. Of course we knew goddamn well we wasn’t going to be up there for a while, so we greeted each other, “Heil Hitler in case we lose,” and this major came in and said, “You assholes.” He was really getting shook up. And so, we made a big joke out of it. Now that’s the last time I seen him. Fetsch ended up there, but see, that was days after. They didn't find him for two and a half days.

Aaron Elson: He said that last night?

Dick Bengoechea: That I don’t know, but that’s what the other guy said. See, Sergeant Vinson, he’s dead. He got the Silver Star, Sergeant Vinson, the first sergeant, he dug a lot of guys out of that. Now it always bothered me, I never knew the town until a few months ago, and I never knew the exact time, or whether it was our plane or theirs. Fifty years, I didn't know any of this stuff. Well, it was ironic. We started a new Purple Heart chapter and the district, he was the original old executive officer in the battalion, in the cavalry days, was the installing officer for the Northwest district [This may have been Dale Albee, who was a sergeant in the horse cavalry and later earned a battlefield commission, although he was not an executive officer]. And so we got to talking. He said he was from the 712th; he's the first guy I talked to in 50 years from the 712th. But I always thought it was a boxcar — these tank cars that blew up, because they was over here about 500 feet on a siding, see. Well, it so happens this Kraut come back over and was gonna blow ’em up; instead it was a carload of black powder. And it left a 50-foot crater, and that's where all the concussion come from, see, and I, what puzzled me, there were pieces bigger than this table of the tank car laying way up along this street. But it always puzzled me, with them bullets coming, why they didn't have a fire? And I finally figured it out about two or three weeks ago, see that tree there? What happened was, the concussion was so great it sucked all the oxygen out of the air and so there was no fire. And the Good Lord was on my right side, I guess.

So Dick Bengoechea always wondered if it might have been an American plane that attacked the railroad siding, which is not an implausible theory because the front was moving so quickly. And Ted Hofmeister thought it was a German fighter being chased by an American P-51. And some of the tankers thought it was a lone German fighter and others thought it was two German planes.

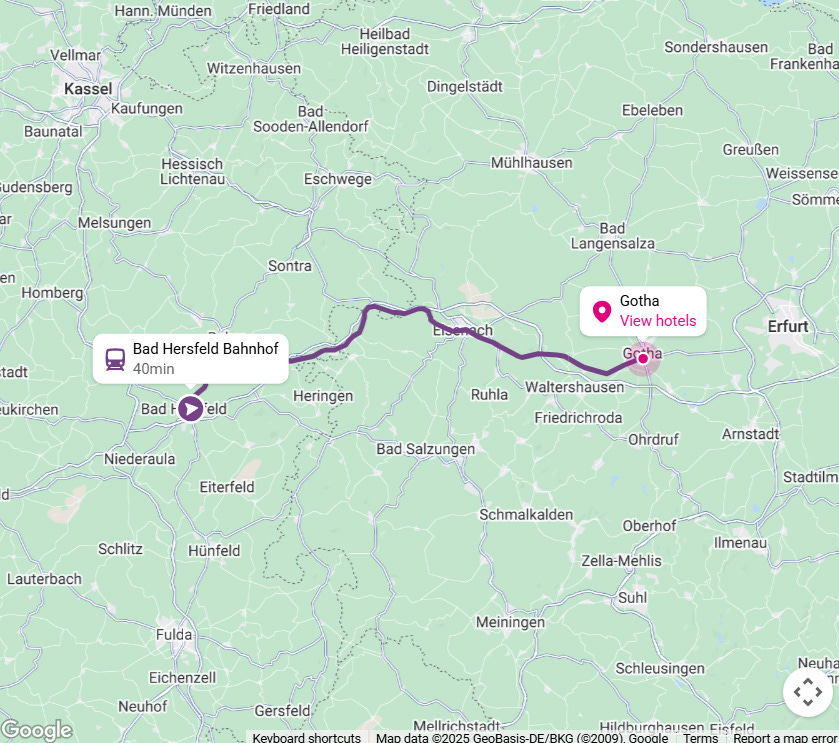

When I was preparing to visit Heimboldshausen in 1999, a light bulb went off in my head. IF, I thought, an American fighter plane was involved, its pilot certainly would have taken credit for shooting down the German plane. So off to the Internet I went, and I found a site for the American Fighter Aces Association. And it had a phone number. So I called, and spoke to a fellow whose name I don’t remember. But I asked if there were any records of an American fighter plane shooting down a German fighter plane on April 3, 1945. Wait one minute, he said, while I look and see. He came back and said there were only four claims of German fighters being shot down by American fighters that day. Then he said something about the vicinity of Gotha, and he gave me the names of the four fighter pilots credited with shootdowns that day.

The vicinity of Gotha, I was a little disappointed until I looked at a map on the Internet. Gotha was less than 50 miles from Heimboldshausen, which isn’t all that much as the P-51 flies (actually, it’s 70 kilometers, which is even less than 50 miles).

I wish I had kept the pilots’ names but I didn’t. However, within a few hours I had spoken to two of them on the phone. Neither recalled a big explosion, which ruled them out. The third had too common a name for me to find him, and the fourth was killed in action a few days after the explosion.

But when I explained that I was planning on visiting the site of the explosion, the fellow from the American Fighter Aces Association said, “If you go, be sure to look up my friend Walter Hassenpflug.”

And that’s how I came to meet Walter Hassenpflug.

The headline on this Substack was “More on the story of Dot and Eddie,” but there wasn’t a heck of a lot in the text about Dot or Eddie. So here is some more of the story. Dorothy Cooney said Eddie rarely spoke about his family, and my father wondered if his fellow lieutenant might not have expected to return from the war. His colleagues in the 712th Tank Battalion described him as an excellent officer but very reserved. He certainly acquitted himself well in combat and was behind the front lines when he was killed in the explosion at Heimboldshausen. In Stockbridge, Massachusetts, he was on his way to becoming one of the town’s prominent citizens. He attended Clark University, taught school, worked in a bank, and was active in the Masons. The Reverend Edmund Randolph Laine, pastor of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Stockbridge, had raised Ed well from the time Ed was 14 and had a falling out with his father.

When I interviewed Elmer Forrest, Ed’s brother, a second time, hoping he would confirm Dorothy’s hint that their mother committed suicide, Elmer confirmed that she did indeed. And then, toward the end of the interview, he gave me copies of a pair of manuscripts. One was written by his grandmother, Hannah Climena Pixley Arial, who was something of a recluse and lived with an unmarried daughter on Beartown Mountain in the Berkshires. She was in her seventies when she dictated it to her daughter, who wrote it down in a school-type notebook with no punctuation. The notebook was found after the grandmother’s death, and Elmer’s niece, Flora Brantley, transcribed it and added punctuation. Flora, whose mother was Vera Louise Forrest, was so moved by the autobiography that she encouraged her mother, who was then in her seventies, to write a similar account of her life. Which she did, and in which she described the death of Eddie’s mother.

Edward, as his sister, two years his junior, called him, was a mama’s boy, she wrote, whereas she gravitated toward her father. The trauma of their mother’s death weighed heavily on both her and Edward.

“The year I was in fourth grade is a year I’ll never forget; a tragic one in my young life,” she wrote. “Before Thanksgiving in October 1923, on a Sunday, Edward, Elmer and I went to Sunday School and church. When we got home, several neighbors were there, also our doctor, Dr. Connors. Dad came out to meet us and told us Mother was very sick with yellow jaundice. She was terribly sick for two weeks, ran a high fever and she was pregnant with her fifth child. [As there were only three siblings, Eddie, Elmer and Vera, she may have lost a child previously]

“A couple of months passed, again we had been to Sunday School and church, when we got home Mother was in bed. Dad said she was ill again, so he gave us our supper and hastened us over to the neighbors across the street, a Mr. and Mrs. Everett Charter. They had a daughter, Pauline, around my age and a boy, Clesson, Edward’s age, and we all were friends. After we left, someone came to the house and gave Dad a drink and by 7 p.m. he was feeling no pain. The doctor came and sent Dad out for the midwife and he came back much later with a woman, Mary Main, and she was so drunk. She lived with a man by the name of Bill Riley and every Saturday and Sunday they’d both be so drunk. The doctor sent her home, got Dad upstairs to bed, called Edward home and he sent him across the covered bridge up Tiger Hill, for a domestic nurse, Clara Beaujon. Mother was furious at Dad even as sick as she was, and around 9 p.m. she gave birth to another baby boy, a blond like Edward. We came home around 11 p.m. and saw Mother and the baby. Again, I was so disappointed it was a boy. I wanted a sister!

“When we got up in the morning, Mother told us she was naming the baby after the President of the United States, Warren Harding, so Warren Joseph Forrest it was. Dad had sobered up enough so that he was able to get our breakifast, and afterwards, Elmer and I were told we had to go away for a couple of weeks so Mother could rest and the house would be quiet. Elmer went to Aunt Nita’s (Mother’s youngest sister) and I was packed off to a cousin of Mother’s, Etta Renfrew, up in Lenox. I was miserable; so homesick, and I guess when I left, they were glad to see me go. I had never been away from home, so I guess I acted real bad. I know I cried a lot. These relatives were practically strangers to me; we had never visited them much and it was so different there. Etta’s old mother, Aunt Lavisie, we called her, Etta’s daughter, Louise, her daughter’s husband, Frank Mattoon, and their small daughter, Barbara, all lived in one house. Every night they’d start arguing over who should pay this and who would pay that. All were afraid one was going to pay out more than the others. I’d lay in bed nights listening to them and cry myself to sleep. All I could do was play paper dolls with little Barbara or mind her while the others were busy. And she was a brat, so spoiled.

“At last my two weeks were up and I came home. Mother was still in bed; complications had set in. (Today I feel she had not been properly taken care of by the doctor. An infection had set in where he had torn her during the birth of the baby. He should of sewn her up.) The pain became so bad that it affected her mind. She never complained and one night she got up and swallowed some poison tablets, Laudlum [Laudanum] tablets that Dad had when he had smashed a thumb, using them to soak his thumb in. Dad caught her and she was rushed to the hospital. There they pumped her stomach, plus they sewed up the vagina after cauterizing it. She healed there, but poor soul, her mind was gone. The day before they took Mother to the hospital, the baby, Warren, kept crying. Nothing we did for him would stop it. He seemed to be in terrible pain. The doctor said he could find nothing wrong with him, so Dad called another doctor and found that the baby wasn’t urinating and he needed to be circumsized. And I, only a girl of ten, held the baby while the doctor did it.

“Several weeks passed and in January a very dear girl friend of mine (Marion Decker, when I was 6, 7 and 8) was taken to the hospital with a brain tumor. She was an only child; her mother had tuberculosis and her father was quite a drinker.

“The baby, Warren, was being cared for by Aunt Nita, who had a baby girl, Florence, a month older than Warren. So it fell on Edward and I to keep house and care for Elmer. We tried real hard to do it and to keep things looking nice. The morning of the 23rd of February (two months after Warren’s birth, December 23, 1923, and my birthday) I was scrubbing the kitchen floor when Edward grabbed my hair brush and spanked me. I just sat in the middle of the floor and bawled. A neighbor came in with a raisin pie for us and a couple of small gifts for me. Then cousin Etta, whose house I had stayed at when Warren was born, came. She finished the floor and helped us clean up the house. We were expecting Mother to come home. Another girlfriend, Luella Goodhind, came and brought me a birthday cake her mother had baked and it was a beautifully frosted three-layer cake. Dad went for Mother, but alas, when he got there she didn’t recognize him so they let her stay longer at the hospital. A couple of weeks later she came home but we realized she wasn’t the same. She would just sit and stare. I had kept my birthday cake for her to see and how it hurt when she never even glanced at it when I lit the candles. And when I cut it, it was so hard and dry we couldn’t eat it.

“The next Sunday, Dad hired a horse and buggy and they went to Aunt Nita’s to see the baby. Mother wanted to bring him home but Dad said not just yet until she got stronger.

“A few mornings later, Dad went to work. Mother seemed better for a few days, so he left her. We children got up and got ready for school and all Mother did was to stand in the window and look out at the river, which was about 200 yards away from the house. Edward realized she was bad again; he set the clock back two hours, told me to stay there till the kitchen clock said 9 a.m. (really 11 a.m.) and went off to school. She began to get wise (I think); started the washing of the clothes. At just 9 a.m. I left, but Edward was late in returning.

“When I came home at noon, one hour later, a woman was washing the clothes in the back room. Mother’s clothes she had on were on the floor and the doctor was there. I went in and never shall I forget the scene I saw. Mother lay on the bed crying so hard and when she saw me she said, “Vera, it’s terrible. I was born white, then I went to see a Chinaman and he made me yellow.” I started to cry and the woman who was there gently put her arms around me and drew me out of the room. She led me to the kitchen where she placed me in a chair. She sat down next to me and told me, Mother had gone out just as soon as I had left and had thrown herself into the river. Mind you, this was March 23rd, 1934, and ice was still on the river in places. A man who was getting off the trolley, in front of the house, saw her and ran and dove in, good clothes and all; he saved her.

“Dad knew then that Mother must be taken care of somewhere else. But in those days, a lot of red tape had to be done before she could be placed in a sanitarium.

“The doctor thought if the baby was home perhaps that would help. So home came baby Warren. And Mother’s mother came to help. But as she was quite old and had been with us a lot before, and she was tired. So a day-nurse was gotten and Dad was with Mother at night. Dad took Mother to the Riggs Foundation, a mental sanitarium in Stockbridge for the wealthy, but the doctors there said her mind was gone, too far for them to help. (Dr. Riggs was the head doctor there.) She appeared no worse from her experience. So Dad made preparations to have her put in the mental hospital in Northampton. Which he dreaded doing.

“Two days later, March 27th, I came home from school at three and the nurse went out for her two hours. She always did this when Edward and I came home. Edward was not home yet. I changed the baby’s diapers and sat by the carriage giving him his bottle. Mother came into the kitchen and asked me to give her the baby. She looked terrible, rather wild eyed, and I said, “He’s almost asleep, Mother, let him sleep.” She rushed out of doors, cut the clothes line down, and then rushed past me and went upstairs to a storeroom where boxes and trunks were kept. She locked the door and evidently tried to hang herself, but the ceiling was too low. I called to a neighbor but she was out. Mother came downstairs again and wanted the baby, but I said, ‘He’s asleep and shouldn’t be awakened.’ She then went to the china closet where unbeknownst to any of us she had hidden some of the poison laudlum tablets that had been used to soak Dad’s thumb when he had smashed it; he thought he had burnt the remaining ones. She went into the bedroom off the dining room and tried to swallow two of them, but they were so large she was unsuccessful. I heard her gagging and I rushed in. I saw what had happened; one had lodged in her throat and was slowly dissolving. I ran screaming to the outside door and attracted another neighbor. She came in, had me run into the pantry, and beat up three eggs and she got Mother out by the sink and we got the eggs down her. This made her throw up and all the poison finally came up. Mrs. Fenn stayed until Edward came home. I was scared stiff. Mother kept crying so hard, it was pitiful. Later she lay down but when Edward went upstairs to change his clothes she got up, came out into the kitchen, had one more poison tablet in her hand, she went and got a drinking glass from the cupboard and dissolved the tablet in it. I screamed, for I thought she meant to drink it. Edward came running downstairs just as she walked over to the stove, where I had potatoes in a pot and a chuck roast in another, she lifted the covers and poured half in each pot and said to us, ‘Don’t tell anyone.’ Then she went in and lay down. I told Edward what she’d done, so he took each pot outside and dumped it all into the garage pail.

“That night she wouldn’t let us children eat with her and Dad in the dining room and all the while Dad was eating she kept raving about all the other women he was running with. Poor Dad, he hadn’t looked at any other woman; little time he had, and he thought so much of Mother. Well, Edward called Aunt Nita and she came and got the baby.

“The next day Mother and Dad went to Lee and the Judge there, Judge O’Brien, made out papers for poor Mother to be sent away to Northampton. She was quiet all day long. She must have realized what was up, but she never let on.

“Night came and before we went to bed, she asked Edward to sing for her. He did, then she kissed us all good night. We went to bed; she sat in her usual place, a large rocker in the dining room. She would never have a light on, just sit and rock.

“The nurse didn’t stay nights as Dad always slept with Mother, so he felt he could watch her, being a light sleeper. Around eleven o’clock, after they had been in bed a couple of hours, he felt her move and get up. He arose and there she was coming back from the kitchen with a potato knife in her hand. He asked her for it and why she had it. She said she just wanted to go upstairs and show it to her children. He got her back to bed and he fell asleep. Poor Dad, he had so little sleep of late that he must have fallen into a sound sleep, for Mother arose and quietly left the room, opened the back door and walked barefooted in her nightgown to the river where she threw herself in. Dad awoke; it must have been just minutes as the bed was still warm. He realized immediately what had happened. He rushed out the door but saw or heard nothing. He called Edward and I. Before I could dress, Edward had dressed, lit a lantern and rushed out and awoke all the neighbors. Hunting parties were formed and by 3 a.m. the whole town was out searching. The local and state police came, and the boy scouts. This was March 29, 1924, and it was cold outside. There had been a light snow but only in spots.

“At 5 a.m. no trace of her body, but several footprints were found leading to the river, so the search was at the river, the Housatonic River. Grappling irons were brought in and there were boats afloat. We children sat on our wood pile and watched it all. At 6 a.m. my father was walking down by the dam, a quarter of a mile from our house, when he thought he saw something, then decided it was just foam, laying up near an old log. He passed by. Edward and his scout master were just behind. Edward climbed a limb of a tree that hung out over the water. He screamed, ‘There she is! There she is!’ It was poor Mother and she was dead. Dad rushed back, threw off his coat and made for the river but two state troopers grabbed him. A boat made its way out to the place and two men lifted her into the boat and brought her to shore. Thank God, I didn’t witness this scene. We had gone through so much already. I felt so sorry for Edward as he idolized Mother. Never did he forget it all. That night always haunted him and he blamed Dad for her death.”